27 Set 2017

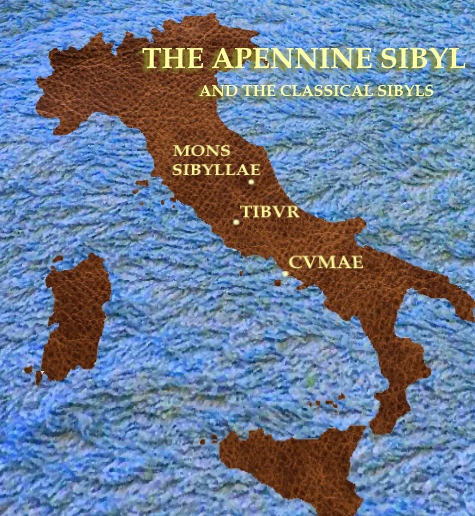

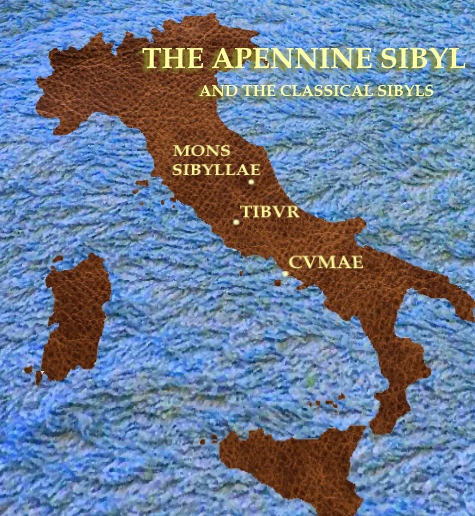

In the name of the Sibillini /2: the Sibyl's Mountains

We don't know why, we don't know when, yet at a certain point in time across the centuries the “Tetrica rupes” (the name of the Sibillini Range in antiquity) seems to turn into something different: the whole mountainous fastness becomes “The Sibyl's Mountains”.

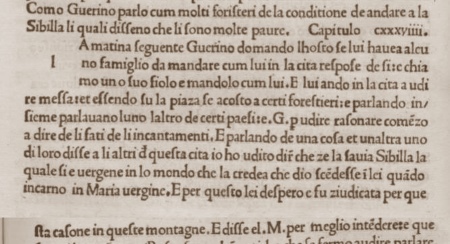

In Chapter 137 of the fifteenth-century romance “Guerrino the Wretch”, the hero is told that the Sibyl «was to be found amid the mountains of the Apennine in the middle of Italy high up a town called Norza, some say it is called Norsia» («li iera in li monti de pinino i[n] lo mezo de Italia sopra una cità chiamata Norza, alcuni dicono como la è chiamata Norsia»); only a few lines ahead, Guerrino asks people «on where is located the Sibyl's mount» («dove era il monte de la Sibilla»). Antoine de La Sale, at the very beginning of his “The Paradise of Queen Sibyl”, reports of a «mount of Queen Sibyl's lake» («mont du lac de la royne Sibille» - today's Mount Vettore) and a «mount of Queen Sibyl» («mont de la royne Sibille»), facing the former.

So, in the fifteenth century no reference to a “Mount Tetricus” can be traced anymore: the Sibillini Range, a portion of the Italian Apennines, is already identified as a mount or group of mounts related to a Sibyl. In addition, no reference to the peak we know today as Mount Vettore can be found at this late Medieval age.

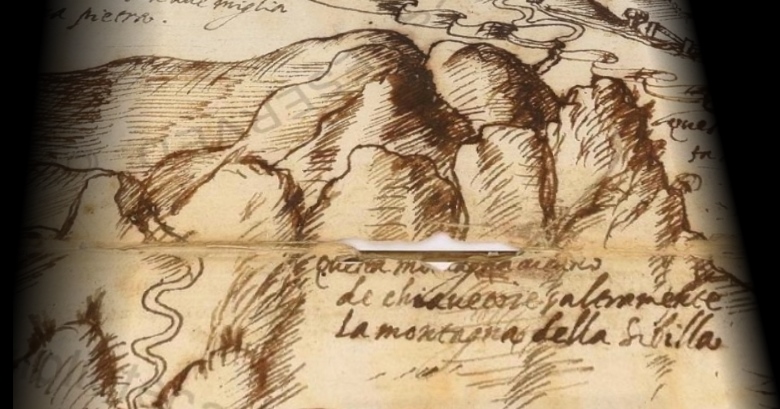

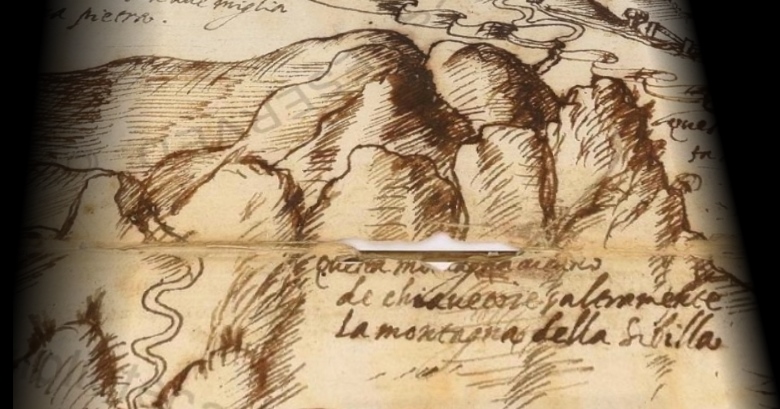

If we jump further ahead in time, we find another clue dating back to 1566: it's the astounding map contained in Vatican manuscript n. 5241, where the whole mountainous massif is referred to with the following sentence: «this mount is called the 'chiavetoie' (Vettore?), also known as The Mountain of the Sibyl» («questa montagna dicono de chiavetoie, altramente La montagna della Sibilla»). Again, no “Tetrica rupes” is present anymore: the drawing shows a mountain range named “of the Sibyl” as a whole; and a first, early reference to something that might be our modern Mount Vettore is now present.

In the subsequent century, Father Fortunato Ciucci, a monk residing in Norcia, concentrates his attention on Mount Vettore. In his “Chronicles of the antique town of Norsia”, written in 1650, he clearly mentioned the «great Mount Vettore [...] its name is Victor owing to his being the greatest, and the best as to magnificence and other qualities» (il «gran Monte Vittore [...] si chiama Vittore per essere di tutti il maggiore, così egli l'istessa qualità ritiene in bellezza ed altre prerogative»). He does not mention a specific mount for the Sibyl, as he rather says that «on the very same Mount Vettore a ghastly Cavern opens its mouth where [...] a mendacious Sibyl has her abode» («nell'Istesso Monte Vittore s'apre un'orrenda Spelonca dove [...] abita una mensogniera Sibilla»).

Nonetheless, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries all the maps of the region show an isolated Mount Sibyl only, with no reference to a Mount Vettore nearby, nor to any larger massif surrounding the renowned peak.

To come full circle, we must get as far as year 1869, when a local scholar, Feliciano Patrizi-Forti, writes his “On the Historical Essays about Norcia”. And here is what he states at page one of his seven-hundred-page work:

«The Apennine massif at whose base Norcia was founded is called 'Mount Sibyl', or 'Mons Tetricus' in antiquity» («Il gruppo appenninico alle falde del quale fu Norcia fondata, è detto 'Monte della Sibilla', anticamente 'Mons Tetricus'»).

In a single sentence, we find the whole transmutation path from the “Tetrica rupes” of the Romans to our modern “Sibillini Range”.

Somewhere along the way, a Sibyl has magically appeared, giving her legendary name to a whole Italian mountainous region: an amazing occurrence that still needs to undergo further investigation and research.

Nel nome dei Sibillini: le Montagne della Sibilla

Non sappiamo né quando, né perché; eppure, ad un certo punto nel corso del volgere dei secoli, la "Tetrica rupes" (il nome dei Monti Sibillini nell'antichità) sembra trasformarsi in qualcosa di differente: l'intero massiccio montuoso diviene "le Montagne della Sibilla".

Nel Capitolo 137 del romanzo quattrocentesco "Guerrin Meschino", al protagonista viene raccontato che la Sibilla «li iera in li monti de pinino i[n] lo mezo de Italia sopra una cità chiamata Norza»; e, poche righe più sotto, Guerrino cerca di raccogliere informazioni su «dove era il monte de la Sibilla». Antoine de La Sale, proprio all'inizio del suo "Il paradiso della Regina Sibilla" riferisce di un «mont du lac de la royne Sibille» (l'odierno Monte Vettore) e di un «mont de la royne Sibille», posto proprio di fronte al primo.

Dunque, nel quindicesimo secolo non è più possibile rintracciare alcuna menzione a proposito di un "Monte Tetrico": il massiccio dei Monti Sibillini, una porzione degli Appennini in terra d'Italia, risulta già essere indicato come una montagna o un gruppo di montagne connesse ad una Sibilla. Inoltre, nessun riferimento al picco oggi conosciuto come Monte Vettore sembra essere reperibile nel volgere di questa tarda età medievale.

Se saltiamo ancora più avanti nel tempo, ci imbattiamo in un ulteriore indizio risalente al 1566: si tratta dell'incredibile mappa contenuta nel manoscritto vaticano n. 5241, dove l'intero massiccio montuoso viene identificato con la seguente frase: «questa montagna dicono de chiavetoie (Vettore?), altramente La montagna della Sibilla». Di nuovo, nessuna "Tetrica rupes" è più presente: il disegno mostra invece un gruppo montuoso denominato nel suo complesso «la montagna della Sibilla», nonché un primo, embrionale riferimento a ciò che noi, oggi, conosciamo come Monte Vettore.

Nel secolo successivo, Padre Fortunato Ciucci, un monaco nursino, concentra la propria attenzione sul Monte Vettore. Nelle sue "Historie dell'antica città di Norsia", scritte nel 1650, egli cita apertamente il «gran Monte Vittore [...] si chiama Vittore per essere di tutti il maggiore, così egli l'istessa qualità ritiene in bellezza ed altre prerogative». Padre Ciucci non menziona alcuna specifica montagna relativa alla Sibilla, limitandosi ad affermare che «nell'Istesso Monte Vittore s'apre un'orrenda Spelonca dove [...] abita una mensogniera Sibilla».

In ogni caso, in tutte le mappe del sedicesimo e diciassettesimo secolo relative a questi territori viene sempre mostrato un isolato Monte della Sibila, senza alcun riferimento ad un adiacente Monte Vettore, né ad alcun massiccio di più vaste dimensioni nelle vicinanze del famoso picco sibillino.

Per chiudere il cerchio, sarà necessario arrivare fino al 1869, quando un erudito locale, Feliciano Patrizi-Forti, pubblicherà il suo "Delle memorie storiche di Norcia". Ed ecco cosa egli scriverà nella pagina iniziale della propria opera da settecento pagine:

«Il gruppo appenninico alle falde del quale fu Norcia fondata, è detto 'Monte della Sibilla', anticamente 'Mons Tetricus'».

In una singola frase, troviamo riassunto l'intero percorso di trasmutazione dalla "Tetrica rupes" degli antichi romani fino ai nostri moderni "Monti Sibillini".

Da qualche parte lungo la strada del tempo, una Sibilla è apparsa magicamente, donando il proprio nome leggendario ad un'intera regione montuosa d'Italia: un evento stupefacente, che necessita certamente di ulteriori studi ed investigazioni.

25 Set 2017

In the name of the Sibillini: the "Tetrica rupes"

Today, 'Sibillini Mountain Range' in Italy is a well-known name, describing a territory where the magnificence of nature harbours a number of mysterious legends. But what was the name of the Sibillini in ancient times?

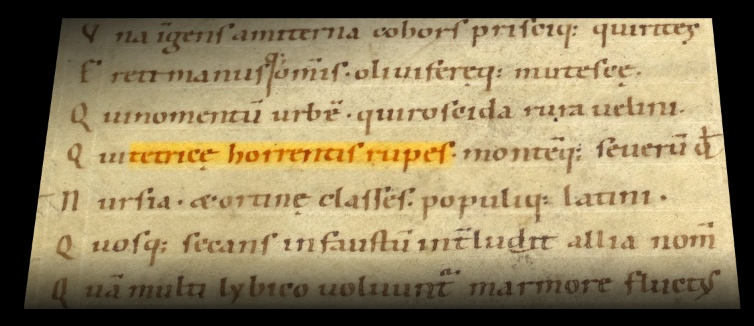

Romans used to call the region “gloomy, frightful mountain” ('Tetrica rupes' in Latin), as mentioned by Vergilius in Book VII of his poem “Aeneid”, when describing the Italian troops that were being sent against Aeneas:

«Ecce Sabinorum prisco de sanguine magnum Agmen

[...] postquam in partem data Roma Sabinis

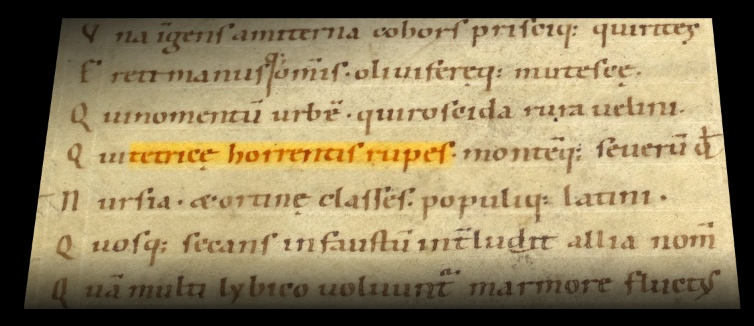

[...] qui Tetricae horrentis rupes

[...] quos frigida misit Nursia»

(«Here comes the great Army of the ancient lineage of the Sabines [...] after Sabines were given a part of Rome [...] those who live at the dreadful Tetricus cliff [...] and those who come from cold, wintry Norcia»)

Servius Marius Honoratus, a fifth century scholar, provides his own comment to the above line by Vergilius ('Commentarii in Vergilii Aeneidos libros', Book VII), by specifying that «the Tetricus mountain is a barren, towering mountain, where stern men are said 'tetricos', sullen and gloomy».

«Tetricus mons in Sabinis asperrimus, unde tristes homines tetricos dicimus»

And Isidore of Seville, in Book X of his “Etymologiarum sive Originum” (sixth century A.D.), adds to Servius' text the following additional remark on the men living at the Tetricus: «inclined to silence, persistently taciturn» («Taciturnus, in tacendo diuturnus»).

The same name 'Tetricus' for the Sibillini Range is also mentioned by Silius Italicus, a Roman consul and poet who lived in the first century A.D. In his work “Punica” (Book VIII), he lists the Italian warriors summoned by the Romans to confront Hannibal at the Battle of Cannae (216 B.C.):

«Hunc Foruli magnaeque Reate dicatum

Caelicolum Matri necnon habitata pruinis

Nursia et a Tetrica comitantur rupe cohortes»

(«With him come the soldiers of [...] Reate sacred to the great Mother of the Gods, and Nursia the abode of snow, and warriors from the Tetricus cliff»).

Furthermore, Marcus Terentius Varro, in Book II of his “De re rustica” (first century B.C.), writes that «even now there are several species of wild cattle in various places. [...] For there are many wild goats in Italy in the vicinity of Mount Fiscellum and Mount Tetrica» («Etiam nunc in locis multis genere pecudum ferarum sunt aliquot. [...] Sunt enim in Italia circum Fiscellum et Tetricam montes multae»).

But what does Varro mean by 'Mount Fiscellum'? The answer is in Pliny the Elder, who in his “Naturalis Historia” (Book III) states that «Velinos accolunt lacus [...] Nar amnis exhaurit illos sulpureis aquis Tiberim ex his petens, replet e monte Fiscello Avens iuxta Vacunae nemora et Reate in eosdem conditus» («in the vicinity of the Lakes of the Velinus [...] the Nar, with its sulphureous waters, exhausts these lakes running towards the Tiber; the river Avens flows from Mount Fiscellus near the groves of Vacuna and Rieti»).

So Pliny, in the above excerpt - which is most probably corrupt - seems to confuse the River Nera (which actually originates in the Sibillini Range) with the River Velino ('Avens'), flowing in and out the Lake of Piediluco, and whose source is found in the area of Mount Terminillo, together with a number of sulphurous springs. Thus the 'Fiscellus Mons' should be better identified with Mount Terminillo.

'Tetrica rupes', gloomy, frightful mountains: such was the name of the Sibillini Mountain Range in antiquity. And - as we will see in a subsequent post - its name will later turn into something different and mysterious: a straight, unequivocal “Mount Sibyl”.

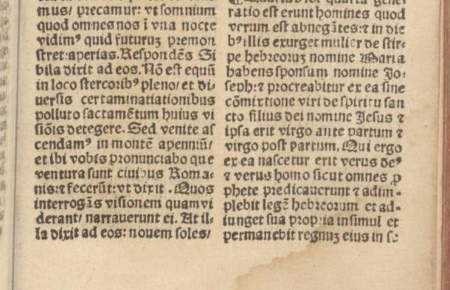

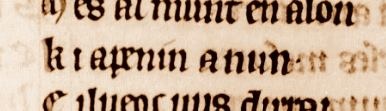

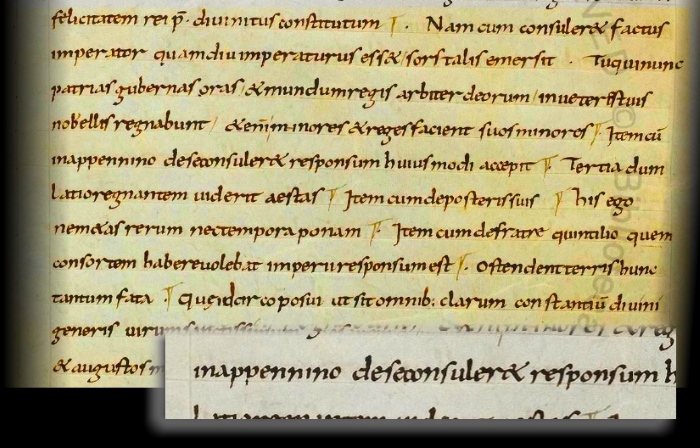

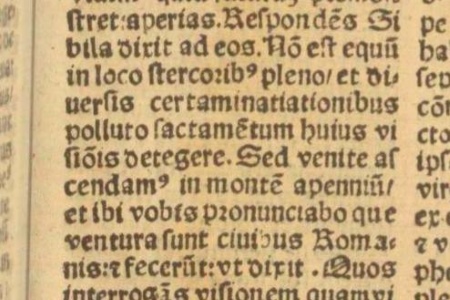

[in the picture: the excerpt from Vergilius'Aeneid containing the sentence on the “Tetricae horrentis rupes” - British Library, manuscript Harley n. 2772, eleventh century]

Nel nome dei Sibillini: la "Tetrica rupes"

Oggi 'Monti Sibillini' è il nome, molto conosciuto, di un territorio presso il quale una natura straordinaria custodisce numerose leggende ricche di mistero. Ma quale era il nome dei Monti Sibillini nel mondo antico?

I Romani chiamavano questa regione "cupa, minacciosa montagna" ('Tetrica rupes' in latino), come riportato da Virgilio nel Libro VII dell''Eneide', con la descrizione delle schiere italiche inviate a fronteggiare l'invasore Enea:

«Ecce Sabinorum prisco de sanguine magnum Agmen

[...] postquam in partem data Roma Sabinis

[...] qui Tetricae horrentis rupes

[...] quos frigida misit Nursia»

(«Ecco giunge il grande Esercito dell'antica stirpe dei Sabini [...] dopo che Roma fu in parte data ai Sabini [...] ecco coloro che venivano dalla spaventosa rupe Tetrica [...] e quelli che furono inviati dalla gelida Norcia»)

Servio Mario Onorato, un erudito del quinto secolo, ci fornisce il suo commento su questo specifico verso di Virgilio ('Commentarii in Vergilii Aeneidos libros', Libro VII), specificando che «lo scosceso e impraticabile Monte Tetrico si trova nella terra dei Sabini, dove gli uomini sono duri e sono chiamati 'tetrici', scontrosi e cupi».

«Tetricus mons in Sabinis asperrimus, unde tristes homines tetricos dicimus»

E anche Isidoro di Siviglia, nel Libro X del suo “Etymologiarum sive Originum” (sesto secolo d.C.), aggiunge al testo di Servio una precisazione relativa a quegli uomini che vivevano presso il Tetrico: «taciturni, inclini al silenzio» («Taciturnus, in tacendo diuturnus»).

Lo stesso nome 'Tetricus' per i Monti Sibillini è menzionato anche da Silio Italico, console e poeta romano vissuto nel primo sec. d.C. Nella sua opera "Punica" (Libro VIII), egli fornisce un elenco delle schiere italiche convocate dai Romani per affrontare Annibale nel corso della Battaglia di Canne (216 a.C.):

«Hunc Foruli magnaeque Reate dicatum

Caelicolum Matri necnon habitata pruinis

Nursia et a Tetrica comitantur rupe cohortes»

(«Assieme ad essi arrivano i soldati di [...] Rieti, sacra alla grande Madre degli Dèi, e Norcia abitata dalle brine, e coorti dalla rupe tetrica»).

Anche Marco Terenzio Varo, nel Libro II del suo "De re rustica" (primo secolo d.C.), scrive che «anche ora ci sono in molti luoghi varie specie di armenti selvatici. [...] Ci sono infatti in Italia molte capre presso i monti Fiscello e Tetrica» («Etiam nunc in locis multis genere pecudum ferarum sunt aliquot. [...] Sunt enim in Italia circum Fiscellum et Tetricam montes multae»).

Ma cosa intendeva Varo per 'Monte Fiscello'? La risposta si trova in Plinio il Vecchio, il quale nella sua "Naturalis Historia" (Libro III) dichiara che «Velinos accolunt lacus [...] Nar amnis exhaurit illos sulpureis aquis Tiberim ex his petens, replet e monte Fiscello Avens iuxta Vacunae nemora et Reate in eosdem conditus» («vicino ai Laghi del Velino [...] il Nera con le sue acque sulfuree esce da questi laghi correndo verso il Tevere; il fiume Avens scorre dal Monte Fiscello vicino ai boschi di Vacuna e Rieti»).

Dunque Plinio, nel brano citato, seppure forse in parte corrotto, sembra confondere il fiume Nera (che nasce in effetti nel massiccio dei Monti Sibillini) con il fiume Velino ('Avens'), che entra nel e fuoriesce dal Lago di Piediluco, e la cui sorgente si trova nell'area del Monte Terminillo, insieme a varie fonti sulfuree. Così il Monte Fiscello è probabilmente da identificarsi con il Monte Terminillo.

'Tetrica rupes', cupa, minacciosa montagna: questo era, nell'antichità, il nome dei Monti Sibillini. E - come vedremo in un successivo post - questo nome si tramuterà in seguito in qualcosa di differente e misterioso: un diretto ed inequivocabile 'Monte della Sibilla'.

[nell'immagine: il brano tratto dall'Eneide di Virgilio contenente il verso sulla “Tetricae horrentis rupes” - British Library, manoscritto Harley n. 2772, undicesimo secolo]

11 May 2017

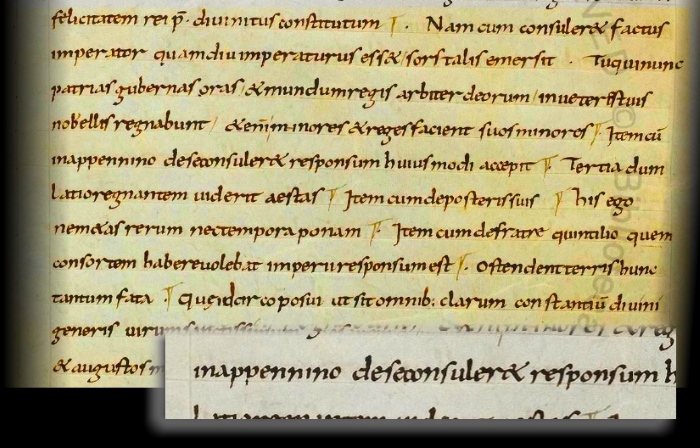

The ritual vigil of a Roman Emperor: Suetonius and the Apennines

We have shown in previous posts that the Apeninnes in Italy have something to do with classical Sibyls (Cumaean, Tiburtine) and oracular shrines (“Historia Augusta”). We can even retrieve a further quote which goes in that same direction: a quote from first-century Latin writer Suetonius, the author of the celebrated work “The Twelve Ceasars”.

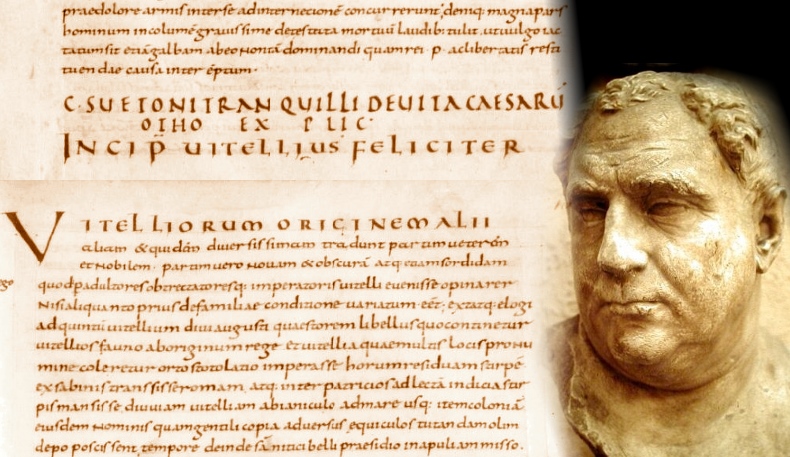

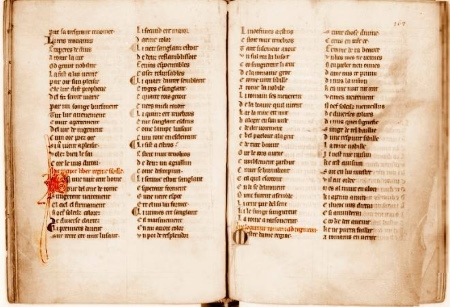

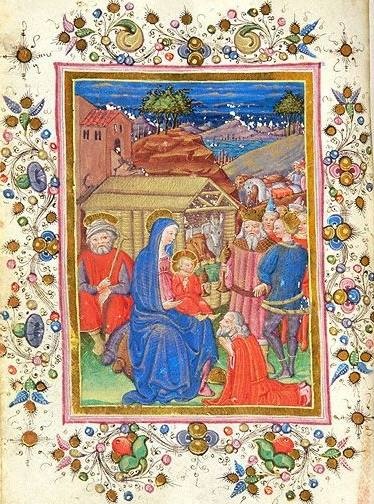

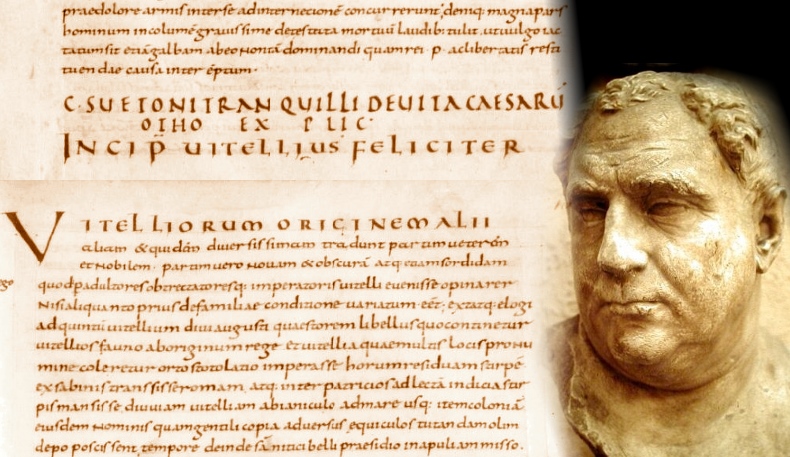

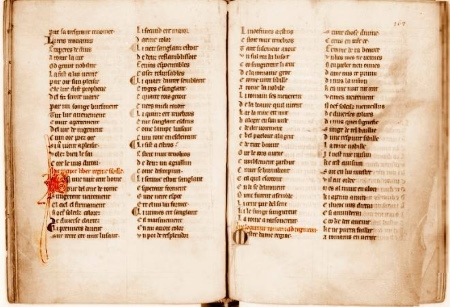

Let's fly through the pages of the most ancient known manuscript handing down to us Suetonius' stories about twelve Roman emperors: it is preserved at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris, under the registration number “Lat 6115”, a treasure coming down straight from the ninth century (see pictures).

In his work, Suetonius recounts the life and deeds of Aulus Vitellius Germanicus Augustus, who reigned as an Emperor after the short-lived Galba and Otho: his rule lasted for nine months only to the end of 69 A.D. when he was slain by partisans of Vespasian.

Aulus Vitellius was a descendant of a «stirpem ex Sabinis», a family originating from the province of Sabina, in central Italy, sitting right on the Apennines. And he probably knew well that this mountainous chain was a peculiar place.

When his legions defeated his rival-Emperor Otho, who finally committed suicide by stabbing himself with a knife, he actually selected the Apennines for a special night of revelling and celebration. In Suetonius' words:

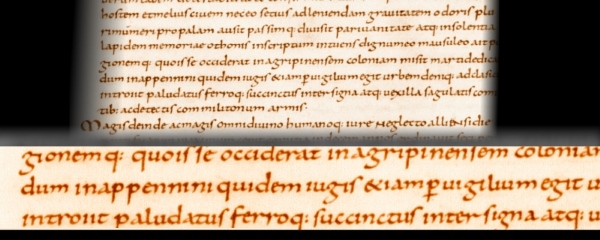

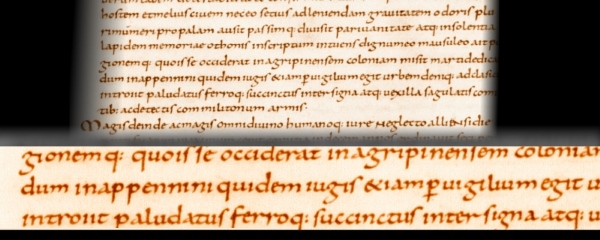

«He openly drained a great draught of unmixed wine and distributed some among the troops. With equal bad taste and arrogance, gazing upon the stone inscribed to the memory of Otho, he declared that he deserved such a Mausoleum, and sent the dagger with which his rival had killed himself to the Colony of Agrippina, to be dedicated to Mars. He also held a ritual vigil throughout the night on the heights of the Apennines. Finally he entered the city (Rome) to the sound of the trumpet, wearing a general's mantle and a sword at his side...».

(in the original Latin text: «plurimum meri propalam hausit passimque divisit. Pari vanitate atque insolentia lapidem memoriae Othonis inscriptum intuens, dignum eo Mausoleo ait, pugionemque, quo is se occiderat, in Agrippinensem coloniam misit Marti dedicandum. In Appennini quidem iugis etiam pervigilium egit. Urbem denique ad classicum introiit paludatus ferroque succinctus...»).

According to Suetonius, Aulus Vitellius left Gaul and, in his course to Rome to be acclaimed as the new victorious Emperor, he stopped one full night with his troops amid the Apennines - his ancestral homeland - for a sacred festival, a sort of thanksgiving to the divine favor.

Again, for ancient Romans the Apennines seemed to be a special place for rites and celebrations. Which mount or valley did Aulus Vitellius exactly select to carry out his vigil? Nobody knows. But sure enough the Apennines had a special attractiveness for oracles, shrines and ritual, devotional practices. The Apennine Sibyl was about to come.

La veglia sacra di un Imperatore romano: Svetonio e gli Appennini

Abbiamo mostrato in precedenti post come la catena degli Appennini presenti una speciale relazione con le Sibille classiche (Cumana, Tiburtina) e i centri oracolari ("Historia Augusta"). Siamo inoltre in grado di rintracciare un'ulteriore citazione che conduce la ricerca nella medesima direzione: parole che sono tratte dagli scritti dell'autore classico Svetonio, vissuto nel I sec. d. C., ed in particolare dalla sua opera più famosa, le "Vite dei Cesari".

Voliamo insieme attraverso i fogli del più antico manoscritto conosciuto contenente l'opera di Svetonio che ci narra dei dodici imperatori romani: è conservato presso la Bibliothèque Nationale de France a Parigi, alla collocazione "Lat 6115", un vero e proprio tesoro che ci arriva direttamente dal nono secolo (cfr. immagini).

Nella sua opera, Svetonio ci racconta la vita e le gesta di Aulo Vitellio Germanico Augusto, che fu imperatore dopo Galba e Otone, entrambi destinati ad un brevissimo regno: anche l'imperio di Vitellio durò solamente nove mesi, fino al termine dell'anno 69 d.C., quando egli fu assassinato dai sostenitori di Vespasiano.

Aulo Vitellio discendeva da una «stirpem ex Sabinis», una famiglia originaria della provincia della Sabina, nell'Italia centrale, situata proprio nel mezzo degli Appennini. E, probabilmente, ben sapeva come questi luoghi fossero unici e speciali.

Quando le legioni di Vitellio sconfissero il suo rivale, l'imperatore Otone, il quale infine si diede la morte con un pugnale, egli decise di recarsi proprio tra gli Appennini per una notte speciale di festeggiamenti e celebrazioni. Nelle parole di Svetonio:

«Egli aprì botti di vino puro e lo distribuì tra i suoi. Con la stessa arroganza e vanità, osservando la lapide scolpita alla memoria di Otone, dichiarò di essere lui stesso degno di un tale mausoleo, e inviò il pugnale con il quale il suo nemico si era ucciso alla colonia di Agrippina, affinché fosse dedicato al Dio Marte. Inoltre, egli celebrò anche una veglia rituale notturna tra i gioghi dell'Appennino. Infine, entrò nella città (Roma) al suono delle trombe, vestito come un generale e indossando la spada...».

(nella versione originale latina: «plurimum meri propalam hausit passimque divisit. Pari vanitate atque insolentia lapidem memoriae Othonis inscriptum intuens, dignum eo Mausoleo ait, pugionemque, quo is se occiderat, in Agrippinensem coloniam misit Marti dedicandum. In Appennini quidem iugis etiam pervigilium egit. Urbem denique ad classicum introiit paludatus ferroque succinctus...»).

Dunque, secondo Svetonio, Vitellio aveva lasciato la Gallia e, nel dirigersi verso Roma per essere acclamato nuovo e vittorioso imperatore, egli si era fermato per un'intera notte con le sue truppe tra le vette dell'Appennino - la terra natìa dei suoi antenati - per una festa sacra, una sorta di ringraziamento reso agli Dèi per il favore concessogli.

Ancora una volta, per gli antichi Romani gli Appennini sembrano rappresentare un luogo molto speciale, presso il quale effettuare riti e celebrazioni. Quale montagna o quale valle aveva scelto Aulo Vitellio per trascorrere la sua veglia sacra? Nessuno lo sa. Ma certamente gli Appennini confermano la propria speciale vocazione per gli oracoli, i luoghi di culto e le pratiche rituali e devozionali. La Sibilla Appenninica stava già per arrivare.

5 May 2017

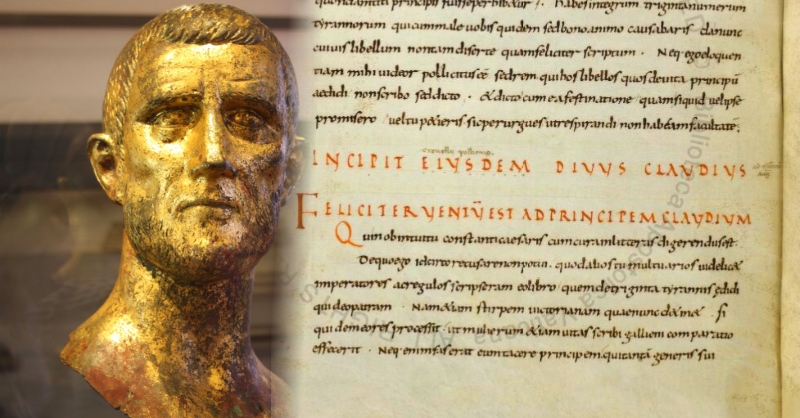

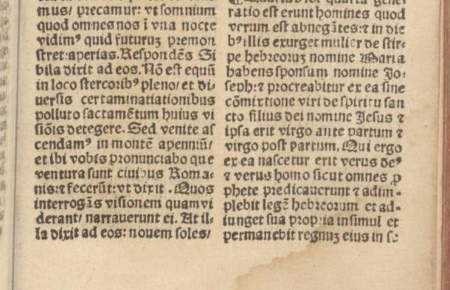

An oracle in the Apennines: the “Historia Augusta”

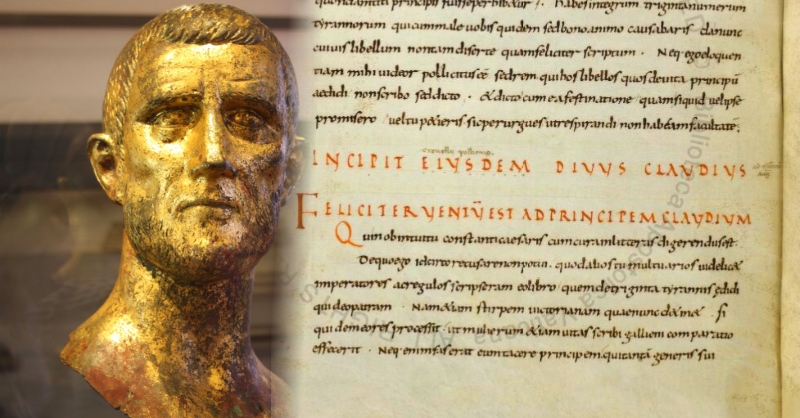

In our effort to trace back the origin of the Apennine Sibyl, we cannot miss a well-known excerpt drawn from the “Historia Augusta”, an antique collection of biographies of Roman Emperors written in the fourth century.

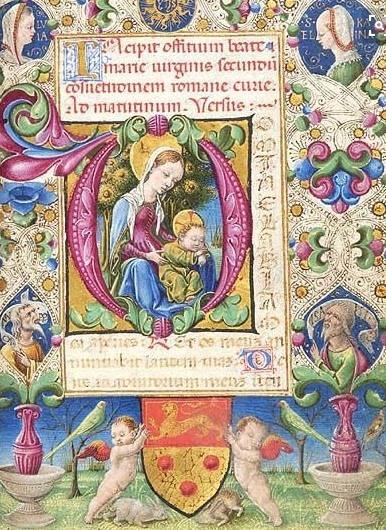

For the first time ever, I will publish here the full text of the excerpt, with pictures of the “Historia Augusta”'s oldest manuscript (ninth century), written in a beautiful carolingian script.

In the section “Divus Claudius” (deified Claudius) written by Latin author Trebellio Pollio and dedicated to Claudius II Gothicus, a soldier of barbarian origin who was proclaimed Emperor by his legions in 268 A.D., we found another important link to an oracle set in the Apennines.

After having asked an oracular response about the fortunes of his lineage in Comagena, a Roman outpost at the frontier with the Noricum (Danube region), Emperor Claudius moves to another oracle. Here is how the excerpt narrates the full story:

«Similarly, when once in the Apennines he asked about his own future, he received the following reply: "Three times only shall summer behold him a ruler in Latium". Likewise, when he asked about his descendants: "Neither a goal nor a limit will I set for their power". Likewise, when he asked about his brother Quintillus, whom he was planning to make his associate in the imperial power, the reply was: "Fate shall display him to people on earth not for long”».

(in the original Latin text: «Item cum in Appennino de se consuleret, responsum huius modi accepit: "Tertia dum latio regnantem viderit aestas”. Item cum de posteris suis: "His ego nec metas rerum nec tempora ponam". Item cum de fratre Quintillo, quem consortem habere volebat imperii, responsum est: "Ostendent terris hunc tantum fata"»).

Once again, we have an oracle who delivers his/her prophecies amid the rugged peaks of the Apennines (the last prophetical statement is a verse from Vergilius' Aeneid). For Romans, Italy's mountainous backbone appears to be a special place, as we have already seen for the Tiburtine Sibyl, who in the legend of the nine suns tells the senators to move with her to the Apennines so as to render her oracular response in a fit, unblemished location.

Has the story of Claudius II Gothicus anything to do with the Apennine Sibyl? Nobody knows: the text provides no further clues, and it might just convey a reference - for instance - to the Tiburtine Sibyl. Yet, it is undeniable that the ancient tale found in the “Historia Augusta” is a confirmation of the fact that the Apennines were a magical place. A most convenient abode for a Sibyl of the Apennines.

Un oracolo negli Appennini: l'”Historia Augusta”

Proseguendo nel nostro tentativo di investigare le origini della Sibilla Appenninica, non possiamo certamente tralasciare una notissima citazione tratta dall'"Historia Augusta", un'antica raccolta di biografie di imperatori romani compilata nel IV secolo.

Per la prima volta in assoluto, pubblicheremo in questa sede il testo completo di questo brano, corredato da immagini del più antico manoscritto esistente dell'"Historia Augusta" (IX secolo), redatto con bellissimi caratteri carolingi.

Nella sezione "Divus Claudius" (Claudio il Divinizzato), scritta dall'autore latino Trebellio Pollione e dedicata a Claudio II il Gotico, un soldato di origini barbare che venne proclamato imperatore dalle sue legioni nel 268 d.C., troviamo questo ulteriore, importante riferimento ad un oracolo localizzato tra gli Appennini.

Dopo avere richiesto un responso oracolare a proposito dei futuri destini della propria discendenza, a Comagena (un avamposto imperiale situato presso la frontiera del Norico, sul Danubio), l'Imperatore Claudio si reca presso un ulteriore oracolo. Ed ecco come l'antico testo ci racconta questa storia:

«Successivamente, essendosi egli recato nell'Appennino per conoscere del proprio futuro, ricevette il seguente responso: "Solamente per tre volte l'estate lo vedrà regnare sul Lazio". Poi, quando egli domandò della propria discendenza: "Io non porrò al loro governo né limiti né confini". E infine, chiedendo del proprio fratello Quintillo, che egli voleva associare nel governo imperiale, gli fu risposto: "Non a lungo i fati lo mostreranno alle genti"».

(nel testo originale latino: «Item cum in Appennino de se consuleret, responsum huius modi accepit: "Tertia dum latio regnantem viderit aestas”. Item cum de posteris suis: "His ego nec metas rerum nec tempora ponam". Item cum de fratre Quintillo, quem consortem habere volebat imperii, responsum est: "Ostendent terris hunc tantum fata"»).

Ancora una volta, troviamo un oracolo che profetizza tra le vette scoscese dell'Appennino (l'ultimo responso profetico è un verso tratto dall'Eneide virgiliana). Per i Romani, la dorsale montuosa dell'Italia sembra essere un luogo speciale, come abbiamo già avuto modo di vedere in relazione alla Sibilla Tiburtina, la quale nella leggenda dei nove soli invita i senatori a seguirla proprio tra gli Appennini, in modo da potere rendere il proprio responso oracolare in un luogo adatto, in quanto incontaminato.

Esiste un legame tra la storia di Claudio II il Gotico e la Sibilla Appenninica? Nessuno può saperlo: il testo non ci fornisce ulteriori indizi, e potrebbe trattarsi semplicemente di un ulteriore riferimento alla Sibilla Tiburtina. Eppure, è innegabile come questo antico racconto tratto dall'"Historia Augusta" costituisca una conferma del fatto che gli Appennini erano un luogo speciale. Una dimora perfetta per una Sibilla degli Appennini.

30 Apr 2017

The origin of the Apennine Sibyl: Cuma or Tivoli? (Part 3)

We have seen in a preceding post that, in antiquity, the Tiburtine Sibyl was reputed to live amid “high mountains” and rendered her oracular responses on the “apennines”. However, this does not imply any direct link to the Apennine Sibyl.

As a matter of fact, and as attested in an excerpt from Servius Marius Honoratus, the Tiburtine Sibyl just had her shrine in Tibur (modern Tivoli): a place whose picturesque setting with waterfalls and ravines, encircled by high mountains, has beguiled not only ancient Roman, but also scores of Grand Tour travellers starting from the sixteenth century and as far as our contemporary era.

In the pictures below, you can see the Temple of the Tiburtine Sibyl as it appears today: the Aniene river plunges its rushing waters down into the precipice opening its jaws just below the shrine, in a sinister gorge called “Valley of Hell”; from there, the water has broken its way further down through a sheer wall of rock, and it is swallowed by a devilish crack where no living being would ever survive if thrown into it.

In classical time, the vista was even more picturesque than today: the “Valley of Hell” was thoroughly flooded with large waterfalls and countless small rivulets oozing from innumerable crevices in the rock wall, like a sort of inhuman kingdom of natural powers (today, the new nineteenth-century waterfall has almost cancelled this liquid show).

«Quae forma beatis ante manus artemque locis!», writes Publis Papinius Statius in his work 'Silvae', containing a portrait of the place, «largius usquam indulsit Natura sibi. Nemora alta citatis incubuere vadis: fallax responsat imago frondibus, et longas eadem fugit umbra per undas. Ipse Anien - miranda fides - infraque superque saxeus hic tumidam rabiem spumosaque ponit murmura, ceu placidi veritus turbare Vopisci Pieriosque dies et habentes carmina somnos» [How kindly the temper of the soil! How beautiful beyond human art the enchanted scene! Nowhere has Nature more lavishly spent her skill. Lofty woods lean over rushing waters; a false image counterfeits the foliage, and the reflection dances unbroken over the long waves. Anio himself — marvellous to believe — though full of boulders below and above, here silences his swollen rage and foamy din, as if afraid to disturb the Pierian days and music-haunted slumbers of tranquil Vopiscus].

That's why the Tiburtine Sibyl was considered as a “mountain”, “apennine” Sibyl. But this had nothing to do with the Apennine Sibyl, hidden in her den in the Sibillini Range area, a very different mountain and natural setting.

L'origine della Sibilla Appenninica: Cuma o Tivoli? (Parte 3)

Abbiamo visto in un precedente post come, nell'antichità, si ritenesse che la Sibilla Tiburtina avesse la propria dimora tra "alte montagne", rendendo i propri responsi oracolari tra gli "Appennini". Tutto questo, però, non permette di stabilire alcuna diretta relazione con la Sibilla Appenninica.

In effetti, come attestato da un brano di Servio Mario Onorato, ciò significa semplicemente che la Sibilla Tiburtina aveva, come noto,la propria sede oracolare a Tibur (l'odierna Tivoli): un luogo le cui pittoresche caratteristiche, con cascate e precipizi circondati da alte montagne, hanno affascinato da sempre non solo gli antichi romani, ma anche decine e decine di viaggiatori del Grand Tour, a partire dal diciassettesimo secolo e fino all'età contemporanea.

Nelle immagini qui proposte, potete osservare il Tempio della Sibilla Tiburtina così come appare ai nostri giorni: il fiume Aniene si getta con acque roboanti nel precipizio che si apre proprio al di sotto del tempio, nella sinistra valle nota con il nome di "Valle dell'Inferno"; da qui, l'acqua si è poi scavata un passaggio che discende ancora più in basso, attraverso una muraglia di roccia viva, e viene infine inghiottita all'interno di una sorta di maligna fessurazione nella quale nessun essere vivente potrebbe mai sopravvivere, se mai dovesse trovarsi a precipitare in essa.

In età classica, lo scenario si presentava in modo ancor più pittoresco di oggi: la "Valle dell'Inferno" era completamente inondata da grandi cascate e innumerevoli rivoli di minori dimensioni, fuoriuscenti dai molteplici orifizi aperti nella roccia, come se si trattasse di una sorta di regno inumano governato dalla potenza della natura (oggi, invece, la nuova cascata realizzata nel diciannovesimo secolo ha quasi completamente cancellato questo affascinante spettacolo d'acqua).

«Che dolce natura ha il suolo, quale bellezza possiedono quei luoghi fortunati», scrive Publio Papinio Stazio nella sua opera "Silvae", che include una descrizione di questi luoghi, «anche senza il lavoro e l’arte dell’uomo. In nessun luogo la natura è stata più generosa verso se stessa. Alti boschi si protendono verso le acque scorrenti, le fronde si moltiplicano in falsi riflessi, e le ombre fuggono sulle onde. L’Aniene stesso – straordinario a credersi – che scorre sassoso a valle e a monte, qui depone la sua tumida furia e i rimbombi spumeggianti, come se temesse di turbare i giorni consacrati alle Muse e i sonni pieni di poesia del sereno Vopisco».

Ed ecco dunque perché la Sibilla Tiburtina è stata sempre considerata come una Sibilla "di montagna", "degli appennini". Ma ciò non ha nulla a che fare con la Sibilla Appenninica, nascosta nel suo elevato rifugio posto nella regione dei Monti Sibillini, una zona montuosa del tutto differente e caratterizzata da ben diversi scenari naturalistici.

20 Apr 2017

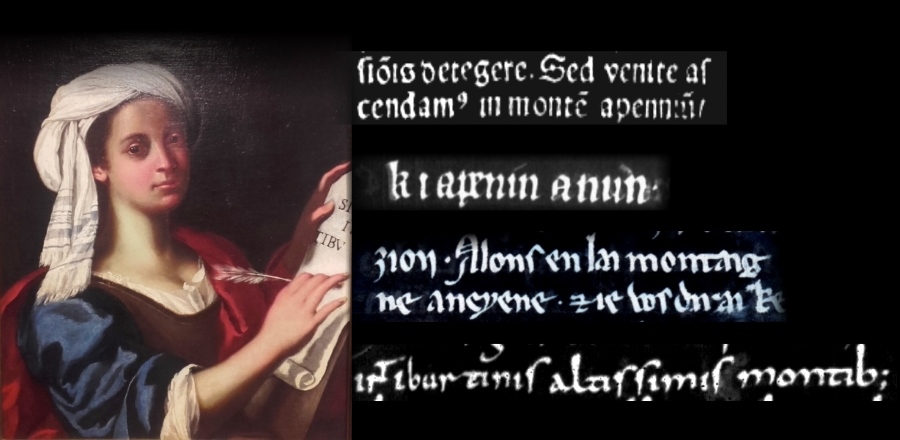

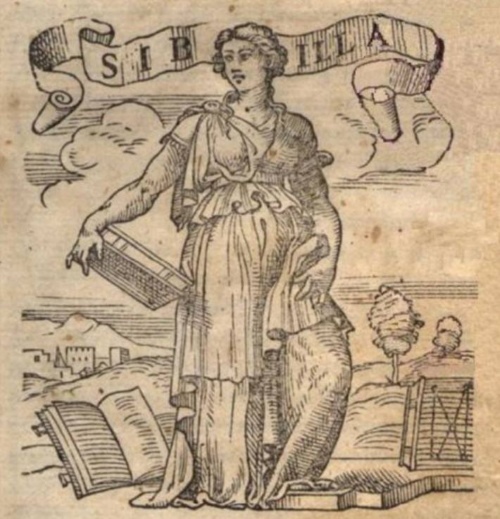

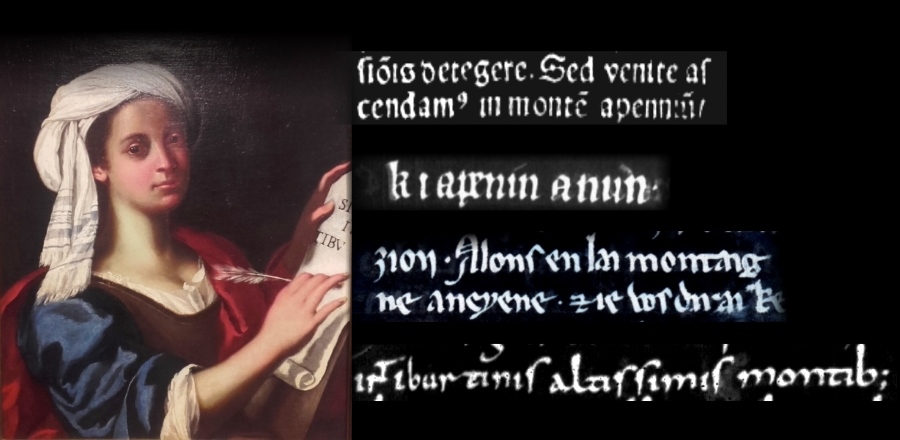

The origin of the Apennine Sibyl: Cuma or Tivoli? (Part 2)

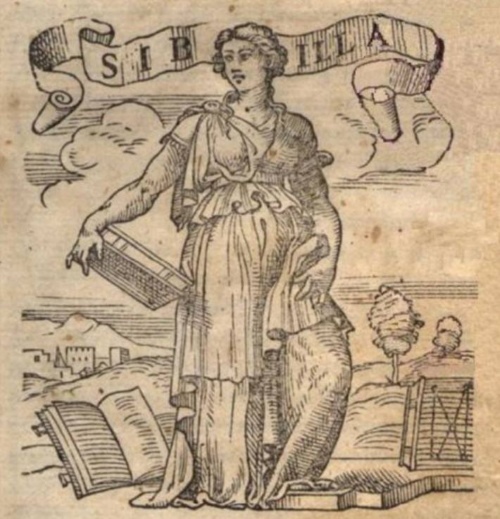

Beside the Cumaean, there is another classical Sibyl as to whom a sort of connection to the Apennine Sibyl might be highlighted: the Tiburtine Sibyl.

The tiburtine oracle is included in the famous list of ten Sibyls reported by Latin author Lactantius in his “Divinae Institutiones”, as a quote from Varro: «the tenth of Tibur, by name Albunea, who is worshipped at Tibur as a goddess, near the banks of the river Aniene, in the depths of which her statue is said to have been found, holding in her hand a book».

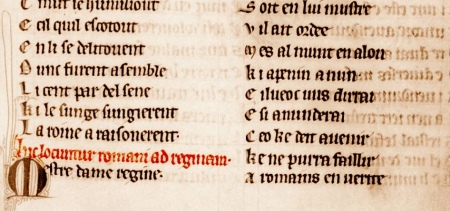

In early-Christian times, the Tiburtine Sibyl was known for the prophecy and legend of the nine suns: a visionary dream made by a hundred Roman senators at the same time, which the Sibyl explained as a succession of historical ages from the Roman empire to the advent of Christianity, future wars and finally the end of the world. The legendary account was copied in dozens of manuscripts across Europe.

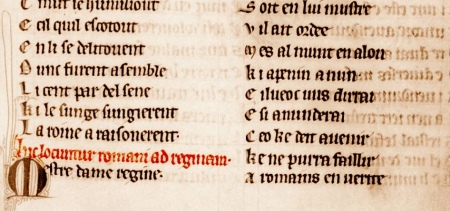

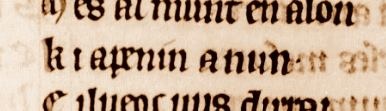

The peculiar aspect about this Sibyl is that she is linked to mountains and the Apennines: in some manuscripts reporting the prophecy of the Tiburtine oracle on the nine suns, she tells the senators that she will provide them with a response «in apenninnum», on the Apennine mountains, considered as a sacred and unblemished place as opposed to corrupted Rome. This same indication is present in “Le Livre de Sibile” (The Book of the Sibyl), a thirteen-century anglo-norman work attributed to Philippe de Thaon, which reports the same Tiburtine Sibyl's episode by saying that the senators should move «ki apenin anun». An old manuscripted French version of the same prophecy dating to 1300 states «alons en la montagne ancyene» ('let's move to the old mountain'). Finally, in the “Liber Mirabilis”, a sixteenth-century book containing a collection of prophecies, the Tiburtine Sibyl invites the Roman senators «in monte apennin».

Could the Tiburtine Sibyl have chosen a remote Apennine peak as her oracular shrine of choice? Could all that refer to the cliff of Mount Sibyl?

The surmise is truly fascinating. However, we must stick to facts (at least literary ones) and there is no evidence of any direct connection between Mount Sibyl and the Apennines mentioned in the Tiburtine oracle's nine-sun legend.

Furthermore, we must consider the illuminating words that Servius Marius Honoratus, a fourth-century scholar, wrote in his “Commentary on Virgil's Aeneid”: «Albunea. [...] quia est in Tiburtinis altissimis montibus». It is clear that the “high mountains” where the Tiburtine (or Albunea) Sibyl used to live are plainly the mountainous ridges at Tivoli, near Rome: they are not as high as Mount Sibyl, nonetheless they are fully impressive and picturesque, with ravines and waterfalls celebrated throughout the centuries by scores of artists and men of letters.

So, the Apennine Sibyl is not the Tiburtine one (if we want to explore a more promising connection, we will have to study the story of the Cumaean). And yet, there is no doubt that by this focus on the oracular Apennines we have shown that in antiquity those lofty mountainous ridges in Italy were considered as a pure and unblemished place: a convenient location for oracles and prophetical responses, as we will also see in the next post.

[in the picture: Tiburtine Sibyl, Anna Bacherini Piattoli, 1750, Collezione Alessandro Marabottini, Palazzo Baldeschi, Perugia (Italy)]

L'origine della Sibilla Appenninica: Cuma o Tivoli? (Parte 2)

Oltre alla Cumana, c'è anche un'altra Sibilla classica per la quale può essere posto in evidenza un qualche tipo di legame con la Sibilla Appenninica: la Sibilla Tiburtina.

L'oracolo tiburtino fa parte della famosa lista di dieci Sibille presente nelle "Divinae Institutiones" dello scrittore latino Lattanzio, una citazione da un testo di Varro: «la decima [Sibilla], tiburtina, nota anche come Albunea, venerata come dea a Tivoli presso le rive del fiume Aniene, dai cui flutti si racconta sia stata tratta una sua statua, reggente un libro nella mano».

Al tempo dei primi Cristiani, la Sibilla Tiburtina era nota per la leggendaria profezia dei nove soli: una visione onirica, sognata da cento senatori romani nel corso della stessa notte; una visione che la Sibilla interpretò come una successione di età storiche, dall'impero romano all'avvento del Cristianesimo, seguiti da conflitti futuri e poi dalla fine del mondo. Il racconto leggendario ci è stato tramandato nei secoli in dozzine di copie manoscritte reperite in tutta Europa.

L'aspetto particolare di questa Sibilla consiste nel fatto che essa è legata alle montagne e all'Appennino: in alcuni manoscritti che raccontano della profezia sibillina relativa ai nove soli, l'oracolo risponde alla richiesta dei senatori dicendo loro che fornirà il proprio responso «in apenninnum», sulle montagne dell'Appennino, considerate come sacre e incorrotte, contrariamente alla sordida Roma. Questa stessa indicazione è presente anche ne "Le Livre de Sibile" (Il Libro della Sibilla), un'opera anglo-normanna del tredicesimo secolo attribuita a Philippe de Thaon, nella quale si racconta il medesimo episodio concernente la Sibilla Tiburtina, la quale esorta i senatori a recarsi «ki apenin anun». Un'antica versione manoscritta in lingua francese della stessa profezia, risalente al 1300, riporta «alons en la montagne ancyene» ('andiamo alla montagna antica'). Infine, nel "Liber Mirabilis", un'opera cinqucentesca che raccoglie una serie di profezie, la Sibilla Tiburtina invita i senatori romani «in monte apennin».

È concepibile che la Sibilla Tiburtina abbia potuto prescegliere un remoto picco dell'Appennino come proprio sito oracolare?

Potrebbe riferirsi, tutto ciò, alla cima del Monte Sibilla?

L'ipotesi è certamente affascinante. D'altra parte, è comunque necessario tentare di rimanere ancorati ai fatti (quantomeno ai fatti letterari) e non possiamo dunque affermare che sussista una qualsivoglia evidenza di un legame diretto tra il Monte Sibilla e gli Appennini menzionati nella leggenda della Sibilla Tiburtina e dei nove soli.

Inoltre, dobbiamo tenere presenti le parole illuminanti che Servio Mario Onorato, un autore del quarto secolo, ha vergato nei propri "Commentari all'Eneide di Virgilio": «Albunea. [...] quia est in Tiburtinis altissimis montibus», dice. È dunque chiaro che gli "altissimi monti" tra i quali la Sibilla Tiburtina (o Albunea) aveva la propria dimora non erano altro che le creste montuose di Tivoli, in prossimità di Roma: esse non sono certamente elevate come il picco del Monte Sibilla, nondimeno si tratta di montagne impressionanti e pittoresche, con scoscesi precipizi e fantastiche cascate, che sono stati resi celebri nei secoli attraverso le descrizioni pubblicate da innumerevoli artisti e letterati.

E così, la Sibilla Appenninica non è la Sibilla Tiburtina (se vogliamo provare ad esplorare un ben più promettente legame, dovremo rivolgerci alle vicende della Sibilla Cumana). Malgrado ciò, non c'è dubbio che, a valle di questa nostra focalizzazione sul ruolo oracolare degli Appennini, abbiamo potuto dimostrare come, nell'antichità, queste alte montagne d'Italia siano state considerate come luoghi particolarmente puri e ancora incorrotti: luoghi adatti, dunque, ad ospitare oracoli e profezie, come avremo modo di vedere nel prossimo post.

[nell'immagine: Sibilla Tiburtina, Anna Bacherini Piattoli, 1750, Collezione Alessandro Marabottini, Palazzo Baldeschi, Perugia]

15 Apr 2017

The origin of the Apennine Sibyl: Cuma or Tivoli? (Part 1)

The Apennine Sibyl seems to have suddenly popped up in the fifteenth century, when she was mentioned for the first time ever in the romance “Guerrino the Wretch” and in De La Sale's “The Paradise of Queen Sibyl”. Did she appear from nothing? Or possibly, is she the heir of the classical Sibyls of the Roman age?

The latter is the right answer, and we may find at least two different ancestors for the Sibyl of the Apennines: both are Sibyls, and both are Italian.

A first lineage takes us back to the Cumaean Sibyl, the most illustrious Italian Sibyl in antiquity. Publius Vergilius Maro writes, in his Aeneid, that «Cumaea Sibylla - horrendas canit ambages antroque remugit - obscuris vera involvens»: terrific riddles she yells, as she sings in her cave, the truth enshrouded in darkness. The Sibilline Books containing the Cumaean Sibyl's prophecies were carefully preserved in a shrine at the Capitoline Hill in Rome.

But why the Cumaean Sibyl should have fled from her famous cave in Cuma to a remote Apennine peak?

Ancient lore reports two different reasons. According to one legendary tradition, the Cumaean prophetess had been a teacher and tutor of the young Holy Mary: in this role she had entertained the idea to take the place of the maiden and become herself the mother of the Son of God. Because of her vile, haughty desire she had been punished and sentenced amid the cliffs of the Apennine.

When Guerrino the Wretch meets the Sibyl, he questions her on this very topic: «O much wise Sibyl, the Divine Grace accorded to you the favour of being the teacher of that virgin who was the mother of the Saviour in his human flesh; how it happened you insanely did not succeed in saving your soul owing to the affliction that overwhelmed you when the deity did not incarnate in your womb?»

But she stops him abruptly and replies angrily that «I was no teacher to our lady. Sir Guerrino, I see you are not so smart as I thought; who ever told you such piece of infomation?». And she continues: «I want you to know my name. I was called 'Cumaean' by the Romans for I was born in a town in the countryside whose name is Cuma: before I was sentenced to this place I lived in the world one thousand two hundred years. When Aeneas came to Italy, I led him through the nether world: and I was seven hundred years old at that time».

Despite all her irritated replies, the Sibyl admits she has been “sentenced” to the craggy fastnesses of the Apennines. If not with relation to the Holy Mary, the reason for that may also be found in the persecutions carried out by early-Christian followers against the Greek and Roman deities, whose temples and shrines were ravaged after the fourth century A.D. Ludovico Ariosto, the author of 'Orlando Furioso', refers to this very lore when he writes «the Cumæan Sibyl [...] who fled, in antiquity, to a Cavern in the territory of Norcia, placed on a mountain-top amidst a gloomy forest, from the charming abode she used to live in at earlier times». A safe den, against the growing threat by the new emerging religion.

The Cumaean Sibyl and the Apennine Sibyl: we just saw that a close link existed between them, so much so that in ancient maps the Lakes of Pilatus, at the very core the Apennine Sibyl's kingdom, bore the same name as the Cumaean prophetess' magical lake: the Lake of Avernus.

Yet, this is not the only lineage up to an ancient Sibyl we can spot today. Another ancestral link does exist to another classical Italian Sibyl: the Tiburtine oracle.

L'origine della Sibilla Appenninica: Cuma o Tivoli? (Parte 1)

La Sibilla Appenninica sembra apparire all'improvviso, nel quindicesimo secolo, quando se ne fa menzione per la prima volta nel romanzo "Guerrin Meschino" e nell'opera di De La Sale "Il Paradiso della Regina Sibilla". Come è possibile che sia apparsa dal nulla? O forse, questa Sibilla è l'erede delle Sibille classiche di età romana?

La risposta giusta pare essere proprio questa, ed è possibile oggi individuare almeno due diverse ascendenze per la Sibilla degli Appennini: si tratta, in entrambi i casi, di Sibille, e di Sibille italiche.

Una prima linea di ricerca ci riporta fino alla Sibilla Cumana, la pià famosa sibilla italica dell'antichità. Publio Virgilio Marone scrive, nell'Eneide, che «Cumaea Sibylla - horrendas canit ambages antroque remugit - obscuris vera involvens»: enigmi paurosi essa canta mugghiando nell’antro, la verità avvolgendo di tenebra. Nell'antica Roma, i preziosi Libri Sibillini, contenenti le profezie della Sibilla Cumana, erano conservati presso il Campidoglio.

Ma perché la Sibilla Cumana avrebbe dovuto abbandonare il suo famoso antro di Cuma per rifugiarsi sulla cima di un isolato picco dell'Appennino?

Le antiche leggende ci raccontano di due diverse possibili cause. Secondo una specifica tradizione, la profetessa di Cuma sarebbe stata la tutrice ed insegnante della giovane Vergine Maria: in tale ruolo, la sacerdotessa avrebbe accarezzato l'idea di prendere il posto della fanciulla e diventare ella stessa la madre del Figlio di Dio. Per questo suo desiderio presuntuoso e indegno, la Sibilla sarebbe stata punita e condannata a trascorrere l'eternità tra le vette dell'Appennino.

Quando Guerrino il Meschino incontra la Sibilla, egli non manca di interrogarla proprio su questo particolare argomento: «O sapientissima Sibilla havendoti conceduta la divina providentia la gratia che tu fosti maestra de quela verzene in cui incarnò el Salvatore de la humana natura, coma p[er]destu el sen[n]o de non te salvare per ché te desperasti se la divinità non des[c]ese in te?»

A queste parole, la Sibilla lo interrompe bruscamente e gli risponde, con ira, di «non essere stata quella che insegna a nostra donna [...] Mis[s]ere Guerino, el tuo sen[n]o non è perfecto come credeva: chi è colui che mostra questo che tu hai dito?». Continua poi: «Io voglio che tu sapi el mio nome. Io fui chiamata da Romani chumana per che io naqui in una cità de campagna che ha nome chumana: e stete al mondo inanzi che io fosse iudicata in questa parte mille e ducento anni, che quando Enea vene i queste parte zoe i Italia, io lo menai per tuto lo inferno: e havea alhora sete cento anni».

Malgrado la risposta alquanto seccata, la Sibilla ammette di essere stata "iudicata", condannata alle remote montagne dell'Appennino. Se non a causa della Vergine Maria, le motivazioni di questa condanna possono essere rinvenute nelle persecuzioni condotte dai primi cristiani contro le divinità greche e romane dopo il IV sec. d.C. Ludovico Ariosto, l'autore dell'Orlando Furioso, sembra riferirsi proprio a questa possibilità quando scrive «la Sibilla Cumea, la qual ridotta / s’era in quei tempi a la Nursina grotta / su gli aspri monti in una selva folta / da i luoghi ameni, ove habitava prima». Un rifugio, dunque, contro le crescenti minacce provenienti dalla nuova religione emergente.

La Sibilla Cumana e la Sibilla Appenninica: abbiamo appena visto come tra di esse sussista uno stretto legame, tanto che nelle mappe antiche i Laghi di Pilato, posti nel cuore del regno della Sibilla Appenninica, sono identificati con il medesimo nome del magico lago della profetessa cumana: il Lago di Averno.

In ogni caso, non è questa l'unica ascendenza che possiamo rinvenire verso un'antica Sibilla. Esiste infatti un altro illustre legame, con un'altra Sibilla dell'Italia classica: la Sibilla Tiburtina.

7 Jan 2017

An Apennine Sibyl from early Middle Ages?

The anglo-norman chronicle from Philippe de Thaun (“Le Livre de Sibile”, XII century) is not by no means the earliest mention of a Sibyl in the Apeninnes.

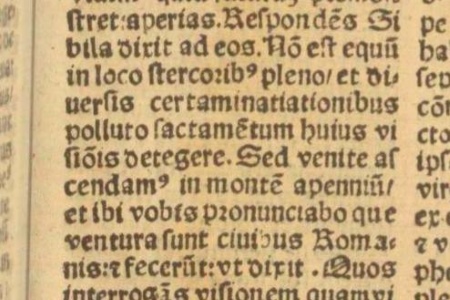

From the earliest centuries of Middle Ages and possibly ever since late Roman times, the Italian Apennines had been connected to Sibyls. Many manuscripts (e.g. Oxford Bodleian Library, manuscript Laud n. 633, XIII sec. - not available online), which report older versions of the “Prophecy of the Tiburtine Sibyl” in Latin, drawn from very ancient manuscripts now lost, speak clearly and plainly of the Apennine. Such older versions were collected in a later work, the “Mirabilis Liber” (1522), which states the following:

«Respondens Sibila dixit ad eos: Non est equum in loco stercoribus pleno, et diversis certaminatiationibus polluto, sacramentum huius visionis detegere. Sed venite ascendam in montem apennin, et ibi vobis pronunciabo que ventura sunt civibus Romanis, et fecerunt, ut dixit.»

(The Sibyl replied to them: it is not convenient, in this unclean place and so polluted by conflicts, to unveil the sacred secrets of this dream. You rather come with me, I will climb the Apennine mount, and there I will foretell to you the fate of Roman citizens; and the Romans did what she had asked them to).

So the Tiburtine Sibyl had spoken to the Roman senators: there was a mount among the Apennines, a special place where she could prophesize conveniently.

Could that place be what we know today as “Mount Sibyl”?

Una Sibilla Appenninica sin dall'Alto Medioevo?

La cronaca anglo-normanna di Philippe de Thaun (“Le Livre de Sibile”, XII sec.) non costituisce affatto la più antica menzione di una Sibilla tra gli Appennini.

Fin dai più remoti secoli dell'Alto Medioevo e probabilmente sin dalla tarda età romana, gli Appennini sono stati legati alle Sibille. Molti manoscritti (es. Oxford Bodleian Library, manoscritto Laud n. 633, XIII sec. - non disponibile online), i quali riportano versioni ancora più antiche della “Profezia della Sibilla Tiburtina” in lingua latina, tratte da manoscritti antichissimi oggi perduti, menzionano chiaramente e palesemente i monti Appennini. Queste antiche versioni furono successivamente raccolte nel “Mirabilis Liber” (1522), che così racconta la profezia della Sibilla:

«Respondens Sibila dixit ad eos: Non est equum in loco stercoribus pleno, et diversis certaminatiationibus polluto, sacramentum huius visionis detegere. Sed venite ascendam in montem apennin, et ibi vobis pronunciabo que ventura sunt civibus Romanis, et fecerunt, ut dixit.»

(Rispose loro la Sibilla: non è confacente, in questo loco impuro e così contaminato dalle lotte, che vengano svelati i sacri segreti di questa visione; piuttosto venite con me, salirò al monte appennino, e lì vi dirò i fati dei cittadini di Roma; ed essi fecero come ella aveva chiesto loro).

Così la Sibilla Tiburtina aveva parlato ai senatori Romani: c'era una montagna, negli Appennini, un luogo speciale dove lei avrebbe potuto pronunciare oracoli in modo confacente.

È possibile che questo luogo fosse ciò che oggi noi conosciamo sotto il nome di “Monte Sibilla”?

6 Jan 2017

The Sibyl and the Apennines in a most precious manuscript dating to the twelfth century

It is not so widely known that the connection between a Sibyl and the Apennine range has not been established in the fifteenth century with “Guerrino the Wretch” and Antoine de La Sale: the link dates back to more than two centuries earlier, as is attested in the valuable manuscript n. 25407 residing in the Bibliothèque Nationale of France.

The manuscript contains “Le Livre de Sibile” (The Book of the Sibyl), an ancient work attributed to Philippe de Thaon, an anglo-norman author of Middle-Age treatises on stones and animals.

In the account reported in “Le Livre de Sibile” (sheet 162), a tale is told about a hundred Roman senators who, during the same night, had the same inexplicable dream, featuring nine multi-coloured suns. The puzzled senators decided to summon the Tiburtine Sibyl to Rome and ask her the meaning of their dream.

But the “regine Sibille” (Queen Sibyl) refused to explain the dream right there in Rome, a place that was unclean; she invited the senators to move to another place more fit to the disclosure of an oracular response: in the anglo-norman text, “ki apenin anun”, all of them should move “to the apennines”.

Thus, here is a first amazing connection between a Sibyl and the Apennines. It is a link established around year 1120. The Apennines, as a proper place for magic and prophecies.

La Sibilla e l'Appennino in un preziosissimo manoscritto del XII secolo

Non tutti sanno che il legame tra la Sibilla e i monti dell'Appennino non risale al 1400 di “Guerrin Meschino” e di Antoine de La Sale, ma a ben due secoli prima, come si rileva nel prezioso manoscritto n. 25407 conservato presso la Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Il manoscritto contiene “Le Livre de Sibile”, antichissima opera attribuita a Philippe de Thaon, nobile autore anglo-normanno di lapidarii e bestiarii medievali.

Nel racconto del “Livre de Sibile”, al foglio 162, si racconta di come, una notte, cento senatori dell'antica Roma sognassero lo stesso incomprensibile sogno, nel quale campeggiavano nove diversi soli multicolori. Perplessi, i senatori decisero di convocare a Roma la Sibilla Tiburtina, oracolo di avvenente bellezza, affinché spiegasse loro il significato del sogno.

Ma la “regine Sibille” si rifiutò di interpretare quel sogno in Roma, luogo impuro; e propose ai senatori di trasferirsi in un luogo adatto alla rivelazione del vaticinio: nel testo anglo-normanno, “ki apenin anun”, che si recassero dunque tutti “nell'appennino”.

Ed ecco un primo, straordinario legame tra una Sibilla e i monti dell'Appennino. Attestato già intorno al 1120. L'Appennino, come luogo congeniale alla magia e ai responsi oracolari.

26 Dec 2016

Guerrino, the Sibyl and the Holy Mary

In the chivalric romance “Guerrino the Wretch” by Andrea da Barberino, a fifteenth-century work, another specific connection between the Apennine Sibyl and the Nativity is mentioned, with a peculiar overlapping between the pagan priestess and the Holy Mary. One of the men asked by Guerrino for information on the Sibyl so replies to him:

«I heard that the wise Sibyl was a virginal maid, so that she had hoped that God would enter into her when the Incarnation occurred in the Holy Mary. Because of that different choice she grieved and was then sentenced amid these mountainous ridges».

The Sibyl, a virgin like the Holy Mary, had aspired to be the chosen one to bear the Jesus in her womb. Yet, God's design was not hers: Mary was chosen and the Sibyl was punished for her overambitious wish and sent to a remote confinement among the Apeninnes.

Guerrino, la Sibilla e la Vergine Maria

Nel romanzo cavalleresco "Guerrin Meschino" di Andrea da Barberino, un'opera risalente al quindicesimo secolo, viene menzionata un'altra specifica connessione tra la Sibilla Appenninica e la Natività di Gesù, con una peculiare sovrapposizione tra la figura della sacerdotessa pagana e quella della Vergine Maria. Uno degli uomini ai quali Guerrino aveva chiesto informazioni a proposito della Sibilla, aveva infatti risposto in questo modo:

«Io ho udito dir che ze la savia Sibilla la quale si è vergene in lo mondo che la credea che dio scendesse i(n) lei qua(n)do incarnò in Maria vergine. E per questo lei desperò e fu ziudicata per questa casone in queste montagne».

La Sibilla, una vergine come Maria, aveva desiderato di essere lei la prescelta per concepire Gesù nel proprio grembo. La volontà di Dio, però, non fu quella di lei: la prescelta fu Maria, e la Sibilla venne punita per il suo ambizioso desiderio, venendo così confinata in un luogo solitario degli Appennini.

25 Dec 2016

The Sibyls who sung the Incarnation

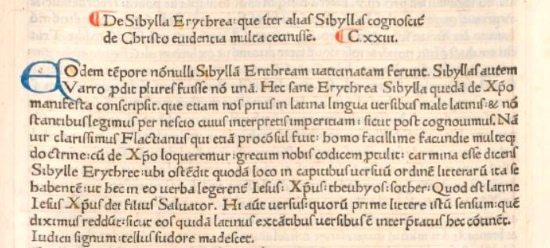

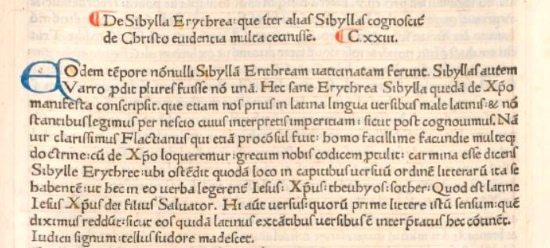

In the fifth century AD, Augustine of Hippo, the great theologian and philosopher, included the Sibyls in the Christian theological system, conferring further life to their legend for the centuries to come. In Book XVIII, Chapter XXIII of his "The City of God" he wrote the following statements about the Sibyls:

«Of the Erythræan Sibyl, Who is Known to Have Sung Many Things About Christ More Plainly Than the Other Sibyls

This sibyl of Erythræ certainly wrote some things concerning Christ which are quite manifest, and we first read them in the Latin tongue in verses of bad Latin, and unrhythmical, through the unskillfulness, as we afterwards learned, of some interpreter unknown to me. For Flaccianus, a very famous man, who was also a proconsul, a man of most ready eloquence and much learning, when we were speaking about Christ, produced a Greek manuscript, saying that it was the prophecies of the Erythræan sibyl, in which he pointed out a certain passage which had the initial letters of the lines so arranged that these words could be read in them in Greek language "Jesus Christ the Son of God, the Saviour." […]

But this sibyl, whether she is the Erythræan, or, as some rather believe, the Cumæan, in her whole poem, of which this is a very small portion, not only has nothing that can relate to the worship of the false or feigned gods, but rather speaks against them and their worshippers in such a way that we might even think she ought to be reckoned among those who belong to the city of God.»

[in the original Latin text]

"Quod fuerit carmen Sibyllae Erythraeae.

Eodem tempore nonnulli Sibyllam Erythraeam vaticinatam ferunt. Sibyllas autem Varro prodit plures fuisse, non unam. Haec sane Erythraea Sibylla quaedam de Christo manifesta conscripsit; quod etiam nos prius in latina lingua versibus male latinis et non stantibus legimus per nescio cuius interpretis imperitiam, sicut post cognovimus. Nam vir clarissimus Flaccianus, qui etiam proconsul fuit, homo facillimae facundiae multaeque doctrinae, cum de Christo colloqueremur, graecum nobis codicem protulit, carmina esse dicens Sibyllae Erythraeae, ubi ostendit quodam loco in capitibus versuum ordinem litterarum ita se habentem, ut haec in eo verba legerentur: , quod est latine: Iesus Christus Dei Filius Salvator. […]

Haec autem Sibylla sive Erythraea sive, ut quidam magis credunt, Cumaea ita nihil habet in toto carmine suo, cuius exigua ista particula est, quod ad deorum falsorum sive factorum cultum pertineat, quin immo ita etiam contra eos et contra cultores eorum loquitur, ut in eorum numero deputanda videatur, qui pertinent ad civitatem Dei."

Le Sibille che cantarono l'Incarnazione

Nel quinto secolo, Agostino di Ippona, il grande teologo e filosofo, incluse le Sibille nel sistema teologico cristiano, conferendo così ulteriore vitalità alla loro leggenda per i secoli a venire. Nel Libro XVIII, Capitolo XXIII della sua opera "La città di Dio", egli così scrisse a proposito delle Sibille:

«Sulla Sibilla Eritrea, la quale è noto abbia cantato molte cose a proposito di Cristo più chiaramente delle altre Sibille.

La Sibilla Eritrea ha certamente e palesemente scritto molte cose concernenti il Cristo, e le possiamo leggere per la prima volta in Latino, in cattivi versi latini, molto dissonanti a causa della goffaggine, come in seguito abbiamo potuto apprendere, di un qualche copista a me ignoto. Perché Flacciano, un uomo molto famoso, che fu anche proconsole, personaggio di prontissima eloquenza e grande erudizione, un giorno che stavamo discutendo di Cristo, tirò fuori un manoscritto in greco, del quale affermava si trattasse delle profezie della Sibilla Eritrea, tra le quali egli evidenziò un certo brano nel quale le lettere iniziali dei versi andavano a formare le seguenti parole, facilmente leggibili, in greco, che significano, “Gesù Cristo figlio di Dio Salvatore.” […]

Ma la Sibilla, fosse essa l'Eritrea oppure, come molti piuttosto ritengono, la Cumana, nel suo poema, del quale quella citata è solo una minima porzione, non solo non contiene nulla che sia relativo al culto dei falsi dèi, ma anche si esprime apertamente contro di essi e i loro seguaci, in un modo tale che noi potremmo anche pensare che essa debba essere riconosciuta tra coloro che appartengono alla città di Dio.»

24 Dec 2016

The Christian Sibyls

In early Christianity, the Sibyls – pagans as they were – were considered as witnesses of the Incarnation. Owing to their vaticinating powers, early-Christian authors reported that the Sibyls had divined the coming of the Son of God, before the actual birth of Jesus in Betlehem. Isidore of Seville, who lived between the sixth and seventh century, wrote in his 'Etymologiae sive Originum' (Book VIII, Chapter 8) the following sentence about the Sibyls:

«Quarum omnium carmina efferuntur, in quibus de Deo et de Christo et gentibus multa scripsisse manifestissime conprobantur» («Songs by all of them are published in which they are attested to have written many things most clearly even for the pagans about God and Christ»)

And that's why the myth of the Sibyl has survived the coming of the new Christian era and the disappearance of the old gods: they were part of God's greater design for the salvation of the world.

Le Sibille cristiane

Tra i primi Cristiani, le Sibille - benché pagane - furono considerate come testimoni dell'Incarnazione. Grazie ai poteri oracolari ad esse attribuiti, gli antichi autori cristiani poterono scrivere che le Sibille avevano preannunciato la venuta del Figlio di Dio, prima dell'effettiva nascita di Gesù a Betlemme. Isidoro di Siviglia, vissuto tra il sesto e il settimo secolo, scrisse nelle sue 'Etymologiae sive Originum' (Libro VIII, Capitolo 8) la seguente frase a proposito delle Sibille:

«Quarum omnium carmina efferuntur, in quibus de Deo et de Christo et gentibus multa scripsisse manifestissime conprobantur» («Sono noti alcuni canti delle Sibille nelle quali esse scrissero molte cose a proposito di Dio e di Cristo, in modo che fossero comprensibili anche ai pagani»)

Ed ecco perché il mito delle Sibille è sopravvissuto all'inizio della nuova età cristiana e alla sparizione degli antichi dèi: esse erano infatti parte del grande disegno di Dio per la salvezza del mondo.

10 Oct 2015

The Sibyl's fairy tale

"Stories often described as fairy tales, be they told in the Caribbean, Scotland or France, can flow with the irrepressible energy of interdicted narrative and opinion among groups of people who have been muffed in the dominant, learned milieux.

The Sibyl, as the figure of a storyteller, bridges divisions in history as well as hierarchies of class. She offers the suggestion that sympathies can cross from different places and languages, different peoples of varied status. She also represents an imagined cultural survival from one era of belief to another. Sibilla exists as a Christian fantasy about a pagan presence from the past, and as such she fulfills a certain function in thinking about forbidden, forgotten, buried, even secret matters. `By my voice I shall be known': it is no bad epitaph for a storyteller."

Marina Warner, "From the Beast to the Blonde - On Fairy Tales and Their Tellers", 1994

La favola della Sibilla

«Storie spesso considerate come mere fiabe, che siano raccontate nei Caraibi, in Scozia o in Francia, possono scorrere con l'irresistibile energia del racconto proibito, circolante tra quei gruppi culturali minori che sono stati soffocati da un ambiente intellettualmente dominante. La Sibilla, come anche la figura del narratore orale, supera le divisioni storiche come anche le gerarchie di classe.

Si tratta di un'immagine che suggerisce come le affinità possano attraversare i valichi tra luoghi e linguaggi differenti, e gente diversa di differente estrazione. La Sibilla rappresenta anche un'immaginaria sopravvivenza culturale da un'era di fede ad un'altra. La Sibilla esiste come una fantasia cristiana che ricorda una presenza pagana proveniente dal passato, e come tale espleta una speciale funzione nel considerare argomenti proibiti, dimenticati, sepolti o anche segreti. “Per mezzo della mia voce io sarò riconosciuta”: non è un cattivo epitaffio per un narratore.»

Marina Warner, "From the Beast to the Blonde - On Fairy Tales and Their Tellers", 1994

25 Sep 2015

A tradition from antiquity

What is a "Sibyl"? In the classical world, Sibyls were women bestowed with the gift of prophecy. They actually spoke on behalf and with the words of a god. Inspired by Apollo, the Sibyl of Delphi chanted the visions that seized her when asked for oracular responses. In Cuma, near Naples, another Sibyl had passed the wisdom contained in her books on to a Roman king, Tarquinius.

The Sibyls were generally considered as priestesses of Cybele, the Phrygian goddess worshipped as a life-giving mother to the earth, amidst the precipitous slopes and ravines of the mountains. The answers they provided were cryptic and easily misunderstood, as men liked to catch of their words just what they craved for within their soul.

Quoting from Varro, an ancient scholar whose work has gone lost, another renowned Latin author, Lactantius, reports that the Sibyls added up to ten. This is the classical list of Sibyls, including the Delphic, the Cumaean, the Tiburtine and others.

Early Christian writers, like Isidore of Seville, claimed that the Sibyls, pagans as they were, had anticipated the coming of Jesus on earth, by predicting the birth of the Son of God. That they would have achieved by using their foretelling faculties.

Yet something seems to be at variance with the classical list of oracular priestesses: in the fifteenth century, another Sibyl, apparently a new one, had made her appearance in a barren region of Central Italy.

That was the Apennine Sibyl. An enduring mystery whose spell is still alive in our present days.

Una tradizione risalente al mondo classico

Che cosa è una “Sibilla”? Nel mondo classico, le Sibille erano donne alle quali era stato conferito il dono della profezia. Esse parlavano nel nome e con le parole di un dio. Ispirata da Apollo, la Sibilla di Delfi cantava le visioni dalle quali era invasa quando richiesta di un responso oracolare. A Cuma, nelle vicinanze di Napoli, un'altra Sibilla aveva trasmesso la saggezza contenuta nei propri libri ad un re romano, Tarquinio.

Le Sibille erano generalmente considerate come sacerdotesse di Cibele, la divinità frigia celebrata come madre vivificatrice della terra, tra i pendii e i paurosi precipizi delle montagne. Le risposte da loro fornite erano enigmatiche ed equivoche, tanto che spesso gli uomini trovavano in esse semplicemente ciò che stavano già desiderando di ascoltare nel profondo del proprio animo.

Citando da Varro, un autore classico la cui opera è andata oggi perduta, un altro famoso autore latino, Lattanzio, racconta che le Sibille erano dieci. Si tratta della famosissima lista delle dieci Sibille classiche, che include la Delfica, la Cumana, la Tiburtina e altre.

Gli apologeti cristiani, come Isidoro di Siviglia, affermavano che le Sibille, benché pagane, avessero annunciato in anticipo l'arrivo del Cristo sulla terra, predicendo la nascita del Figlio di Dio. In ciò, esse avrebbero fatto uso delle loro capacità di preveggenza.

Qualcosa, però, sembra non trovare corrispondenza nella lista classica delle sacerdotesse oracolari: nel quindicesimo secolo, un'altra Sibilla, apparentemente una nuova Sibilla, aveva fatto la propria apparizione in una sperduta regione dell'Italia centrale.

Si trattava della Sibilla Appenninica. Un mistero che dura da secoli, e il cui incantesimo è ancora vivo ai nostri giorni.