8 Sep 2017

Tannhäuser vs. Apennine Sibyl: who copied from whom?

As anticipated in a previous post, the German legend of Tannhäuser, with its Venusberg, is so similar to the Italian lore about Mount Sibyl that there is no doubt among scholars that the two legends arise from the same stem: they are almost identical.

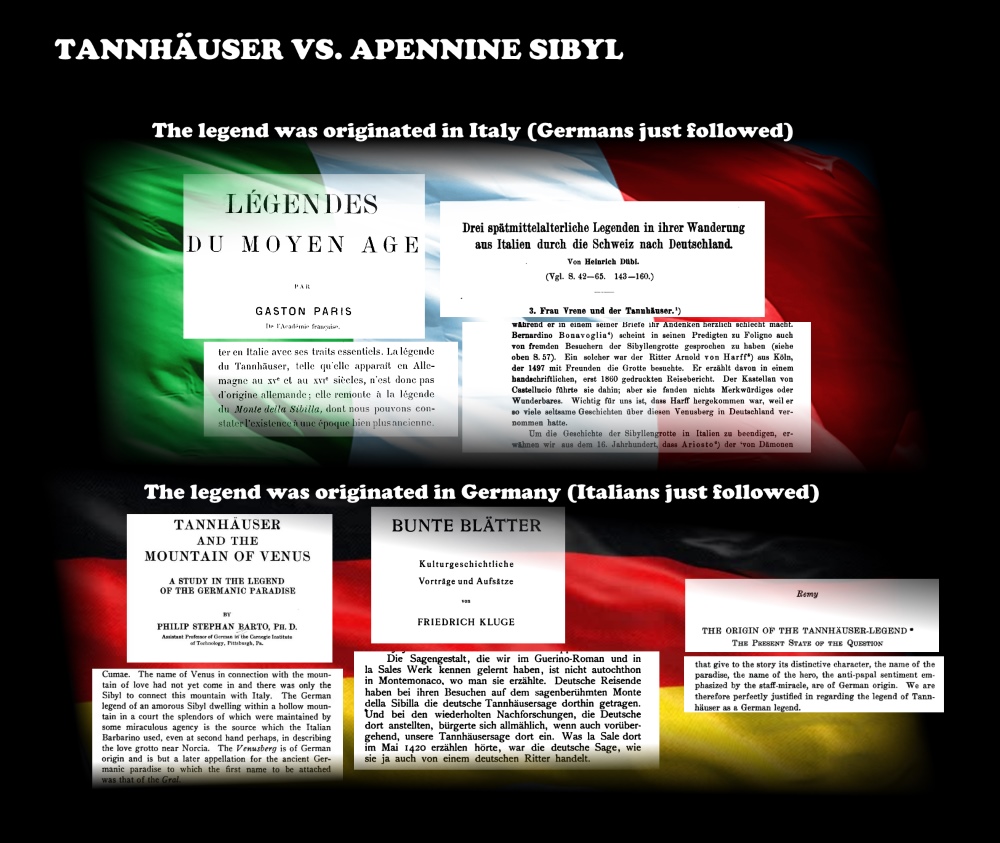

Following this consideration, extensive investigation has been carried out throughout more than a century to answer a most sensitive question: the Venusberg / Mount Sibyl legend was first born in Germany or Italy?

The prize at stake is the original “authorship” of the myth: who copied from whom? Needless to say, German scholars embrace the “German theory”, while Italian and French researchers like better the “Italian conjecture”... Let's have a quick look at both.

>>> THE “ITALIAN CONJECTURE”

In 1903, the great French philologist Gaston Paris was the first to support the idea of a native Italian origin of the legend.

The basic fact is that Andrea da Barberino with his “Guerrino the Wretch”, the earliest work which mentions Mount Sibyl and an Apennine Sibyl, is positively set in Italy; furthermore, Antoine de La Sale wrote his “Paradise of Queen Sibyl” only a few decades later, and this work too is set in Italy, near the town of Norcia.

According to the “Italian conjecture”, the legendary tale, with its peculiar fascination, travelled as far as Germany through Switzerland: the Italian hero was replaced with a suitable German figure, that of Tannhäuser, a wandering poet and knight who had actually lived an adventurous life two centuries earlier. The Sibyl, a character of the classical world, was substituted by Venus, a possible recollection of ancient German deities such as Holda or Freia.

A further clue in support of the “Italian conjecture” is the fact that Tannhäuser, on leaving the 'Venusberg', immediately proceeds to Rome in order to ask for forgiveness, and such behaviour is only compatible with an original Italian setting of the legend.

This vision is also supported by Heinrich Dübi, who provides a most important quote drawn from Felix Hemmerlin, a Swiss who in the first half of the fifth century clearly stated the identity of the 'Venusberg' and the Mount Sibyl, both to be located in Italy.

Thus, the 'Venusberg' legend is fully Italian, though subsequently adapted to the cultural needs and taste of Germans.

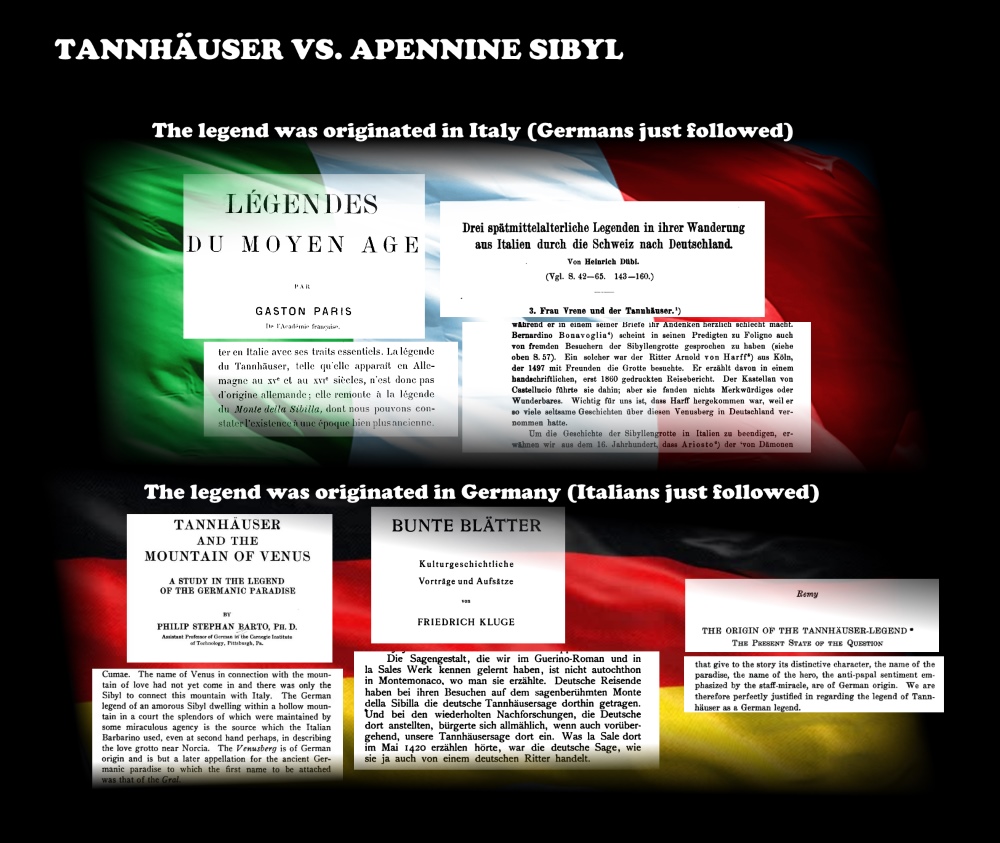

>>> THE “GERMAN THEORY”

However, there is also an utterly different point of view: the “German theory”. Actually other researchers hold that the entire myth was transplanted from Germany to Italy, presumably by travelling scholars.

As contended by Philip Stephan Barto, Italy just received the myth from Germany. Apart from Andrea da Barberino and Antoine de La Sale, the vast majority of literary quotes referring to Mount Sibyl as the subterranean realm of a fairy comes from German authors, and the largest number of travellers arriving to the Italian Mount Sibyl are of German origin. For instance, the tales recounted by Antoine de La Sale as having been told to him by Mount Sibyl's local peasants mostly refer to German travellers.

Friedrich Klüge pushes himself as far as to say that «German travellers during their visits to the famed Mount of the Sibyl have carried thither the German Tannhäuser legend. And thanks to the repeated investigations which Germans made in those parts our Tannhäuser legend gradually although temporarily became there established. What La Sale heard related there in May 1420 was the German legend...». And Arthur F. J. Remy adds that even Swiss mercenaries, abundantly present in Italy from the fourteenth century on, may have transported the legend to Italy.

In addition to that, many quotations about the Italian mount seem always to originate from a German setting (e.g. Felix Hemmerlin, Arnold of Harff, and others), and some of the quotes coming from Italian men of letters actually refer to Germans (e.g. a famous letter by Silvio Enea Piccolomini, who mentions the Sibyl only because urged by a question posed to him by a Saxon scholar).

Finally, the earliest reference to the Apennine Sibyl in Italy is made by Andrea da Barberino: nobody has ever been able to trace the ascendant to that story. Where did Barberino take his tale from? In Italy, no older reference has ever been found. Possibly, Andrea da Barberino got the idea from the German's Tannhäuser lore, which had been circulating in Germany since a century earlier.

Not enough? Mr. Barto also notes that the Italian version of the story, based on the Cumaean Sibyl that would have allegedly moved from Cumae and settled into the mount near Norcia, is marked by the lack of any ground in the classical sibilline mithology of ancient times. There is no evidence of such transfer in any ancient source.

So, according to the “German theory” Italians would have just been fooled by tales originated in Germany; this is confirmed by the fact that, owing to the foreign origin of their Mount Sibyl's legend, Italy has never developed any real interest in it.

>>> SO WHO'S IN THE RIGHT?

Which model is the true one? The “Italian conjecture” by Gaston Paris, Heinrich Dübi and others (Sibyl's legend - Italian origin) or the “German theory” by Philip Stephan Barto, Friedrich Klüge and Arthur F. J. Remy (Sibyl's legend - German origin)?

The truth lies presumably in the middle, as we will see in a subsequent post.

Tannhäuser e la Sibilla Appenninica: chi ha copiato da chi?

Come anticipato in un precedente post, la leggenda tedesca di Tannhäuser, con il suo Venusberg, risulta essere così simile alla tradizione italiana relativa al Monte Sibilla che non può sussistere alcun dubbio in merito al fatto che le due leggende abbiano avuto origine dalla stessa fonte: esse sono infatti praticamente identiche.

Seguendo questa considerazione, per oltre un secolo gli studiosi hanno condotto approfondite ricerche al fine di poter rispondere ad una domanda estremamente delicata: la leggenda del Monte Sibilla / Venusberg è nata prima in Germania o in Italia?

La posta in palio è la "paternità" stessa del mito: chi ha copiato da chi? Non c'è bisogno di dire come, naturalmente, gli studiosi tedeschi abbraccino la "teoria teutonica", mentre italiani e francesi preferiscano molto di più l'"ipotesi italica"... Diamo una breve occhiata ad entrambe.

>>> L'”IPOTESI ITALICA”

Nel 1903, il grande filologo francese Gaston Paris fu il primo a sostenere l'idea di un'origine italiana della leggenda.

Il fatto principale è che Andrea da Barberino con il suo "Guerrin Meschino", l'opera più antica nella quale si menzioni il Monte Sibilla e anche una Sibilla Appenninica, è indubbiamente ambientato in Italia; inoltre, Antoine de La Sale scrive il suo "Paradiso della Regina Sibilla" solamente pochi decenni dopo, e anche la sua opera ha un'ambientazione italiana, in prossimità della città di Norcia.

Secondo l'"ipotesi italica", il racconto leggendario, caratterizzato da un fascino peculiare ed intenso, avrebbe viaggiato fino alla Germania, passando per la Svizzera: l'eroe italiano sarebbe stato sostituito da una figura tedesca più adatta, quella di Tannhäuser, un cavaliere e poeta errante che aveva effettivamente vissuto una vita avventurosa due secoli prima. La Sibilla, un personaggio tipico del mondo classico, sarebbe stata sostituita da Venere, una possibile reminiscenza di antiche divinità germaniche come Holda o Freia.

Un ulteriore indizio a conferma dell'"ipotesi italica" è costituito dal fatto che Tannhäuser, nell'abbandonare il 'Venusberg', si reca immediatamente a Roma al fine di ottenere il perdono papale: un comportamento compatibile solamente con una ambientazione italiana dei luoghi della leggenda.

Questa visione è sostenuta anche da Heinrich Dübi, il quale fornisce un elemento di fondamentale importanza: una citazione tratta da Felix Hemmerlin, uno svizzero il quale, nella prima metà del quindicesimo secolo, dichiara senza dubbio alcuno che il 'Venusberg' è in realtà il Monte Sibilla, e che esso si trova in Italia.

Dunque, la leggenda del 'Venusberg' sarebbe tutta italiana, benché successivamente adattata al gusto e ai bisogni culturali delle popolazioni germaniche.

>>> LA “TEORIA TEUTONICA”

Ma c'è anche un punto di vista totalmente differente: la "teoria teutonica". In effetti, altri ricercatori sostengono invece che l'intero mito sia stato trapiantato in Italia dalla Germania, probabilmente grazie a "clerici vagantes".

Come puntualizzato da Philip Stephan Barto, l'Italia avrebbe semplicemente ricevuto la leggenda dalla Germania. Ad esclusione di Andrea da Barberino e Antoine de La Sale, la grande maggioranza delle citazioni letterarie che si riferiscono al Monte della Sibilla come ad un regno sotterraneo abitato da un'incantatrice provengono da autori tedeschi, e molti dei viaggiatori in visita presso il Monte Sibilla in Italia sono di origine tedesca. Ad esempio, i racconti menzionati da Antoine de La Sale, a lui riferiti dai contadini del posto, si riferiscono prevalentemente a viaggiatori tedeschi.

Friedrich Klüge si spinge addirittura a dire che «sono stati proprio i viaggiatori tedeschi in visita al famoso Monte della Sibilla ad avere trasportato fin lì la leggenda tedesca di Tannhäuser. E grazie alle ripetute visite effettuate dai tedeschi in quelle lande, la leggenda di Tannhäuser si radicò gradualmente, seppure temporaneamente, in quei luoghi. Ciò che de La Sale udì raccontare nel maggio 1420 era proprio la leggenda tedesca...». E Arthur F. J. Remy aggiunge anche che potrebbero essere stati i mercenari tedeschi, abbondantemente presenti in Italia a partire dal quattordicesimo secolo, a trasportare la leggenda nella stessa Italia.

Oltre a ciò, molte citazioni a proposito della montagna italiana sembrerebbero originarsi proprio in ambienti di lingua tedesca (ad es., Felix Hemmerlin, Arnold di Harff e altri), e alcune delle citazioni rinvenibili nelle opere di letterati italiani sembrano riferirsi in effetti a tedeschi (es. la famosa lettera scritta da Silvio Enea Piccolomini, il quale menziona la Sibilla solo perché sollecitato da una domanda postagli da uno studioso della Sassonia).

Infine, la più antica menzione della Sibilla Appenninica in Italia sembrerebbe essere proprio quella di Andrea da Barberino: nessuno ha mai potuto reperire una versione più antica di questa storia. Da dove la trasse l'autore del "Guerrino"? In Italia, non è stato possibile trovare alcun riferimento precedente. Forse, Andrea da Barberino prese l'idea dal mito tedesco del Tannhäuser, che circolava in Germania sin dal secolo precedente.

Basta così? No, perché Barto segnala anche come la versione italiana della storia, basata sull'ipotesi di una Sibilla Cumana che si sarebbe trasferita da Cuma ai monti in prossimità di Norcia, sembri essere marcata dalla totale mancanza di conferme che siano basate sulle fonti classiche del mito sibillino. Non esiste alcuna evidenza di questo supposto trasloco in nessun autore classico.

Così, secondo la "teoria teutonica" gli Italiani si sarebbero fatti prendere per il naso da racconti provenienti, in realtà, dalla Germania; ciò sarebbe confermato dal fatto che, essendo straniera l'origine della leggenda del Monte Sibilla, l'Italia non ha mai sviluppato un vero interesse verso questa storia.

>>> MA ALLORA CHI HA RAGIONE?

Dov'è la verità? Nell'"ipotesi italica" di Gaston Paris, Heinrich Dübi e altri (leggenda della Sibilla - origine italiana) o nella "teoria teutonica" di Philip Stephan Barto, Friedrich Klüge e Arthur F. J. Remy (leggenda della Sibilla - origine tedesca)?

La verità si trova probabilmente nel mezzo, come vedremo in un post successivo.

6 Sep 2017

The German knight who travelled to the Sibillini Range: the Tannhäuser's legend

«Now in truth has my poem begun

Of Tannhäuser I will sing thee

And of the wonders he hath done

With Venus, the noble courtly Lady.

Tannhäuser was a sturdy man

In quest of wonders he

did wish to enter Venus' Mount

Where pretty women be».

This is the famous opening of one of the most popular poems ever written in Germany: the “Song of Tannhäuser”, whose earliest versions date back to the fifteenth century. The German poem is usually made up by 25-30 stanzas each including four lines. It tells the tale of a knight and poet who lives a revelling, sinful life at the court of Dame Venus, the goddess of love.

And the fairy court of the deity is placed under a mountain, called 'Venusberg' or 'Frau Venus Berg'.

Tannhäuser fears for the salvation of his immortal soul, he wants to leave the goddess' subterranean realm and ask forgiveness for his sins:

«My life has grown a burden here,

I would not longer tarry;

So give me leave now to depart

From thee, o beautiful fairy!»

The goddess will try to prevent him from leaving the cave, yet Tannhäuser will rush out and head to Rome, where he will implore Pope Urban IV to forgive him. But the Pope will not accept to bestow his absolution on him, so Tannhäuser - now a man condemned by God and an outcast - will trace his own steps back to the 'Venusberg' and, with disconsolate soul, enter into the subterranean realm again, leaving our world forever.

A mountain and a knight; a subterranean kingdom, full of enchantment, where a goddess and sorceress had established her abode; an unholy stay among unchaste maidens, of gorgeous, divine fairness; the shameful remorse, the feeling of dread for his inexcusable guilt; the ghastly vision of hellfire; the frantic escape from the enthralling spell; the attempt to seek a forgiving blessing from the Pope in Rome.

All of them are manifest, bewildering coincidences with another tale, written by an Italian author in the fifteenth century.

The tale is “Guerrin Meschino” by Andrea da Barberino. And the mount is Mount Sibyl, in Italy.

Are the Venusberg and Mount Sibyl the same mountain? Is the legend of Tannhäuser actually set in Italy, within the lofty peaks of the Sibillini Range? Is there a close connection between the German legend of Dame Venus and the Italian legend of the Sibyl?

For more than a century the question has been addressed by scholars, men of letters and philologists in many books and articles. And the answer is that a connection does exist: the two legends are basically the same legend. And the 'Venusberg' might actually have been placed in the vicinity of Norcia.

At Mount Sibyl.

[You can download a high-quality, high-resolution version of the fine Tannhäuser's miniature contained in the precious fourteenth-century Manesse Codex (Bibliotheca Palatina of Heidelberg) from here]

Quel cavaliere tedesco che visitò i Monti Sibillini: la leggenda di Tannhäuser

«Ora comincia invero il mio poema

di Tannhäuser io ti canterò

e delle meraviglie da lui vissute

con Venere, la nobile Dama.

Tannhäuser fu uomo forte

in cerca di cose mirabili egli

bramò entrare nella montagna di Venere

ove sono donne bellissime».

Questo è il celebre incipit di uno dei più noti poemi mai scritti in Germania: il "Canto di Tannhäuser", le cui versioni più antiche risalgono al quindicesimo secolo. Il poema tedesco, composto nelle varie versioni da 25-30 strofe in quartine, racconta la storia di un cavaliere e poeta che vive una vita peccaminosa e dissoluta alla corte della Dama Venere, la dea dell'amore.

E la corte fatata della divinità si trova sotto ad una montagna, chiamata 'Venusberg' o 'Frau Venus Berg'.

Tannhäuser teme per la salvezza della propria anima immortale; egli desidera abbandonare il mondo sotterraneo e recarsi a chiedere perdono per i propri peccati:

«La vita mia qui mi opprime,

oltre io non indugerò;

lascia dunque che io parta

e mi separi da te, o meravigliosa fata!»

La dea tenterà di impedire al cavaliere di abbandonare la caverna, ma Tannhäuser riuscirà a fuggire e si dirigerà verso Roma per implorare l'assoluzione di Papa Urbano IV. Il Papa, però, non accetterà di concedere la propria benedizione; così Tannhäuser - uomo reietto e ormai condannato da Dio - ritornerà sui propri passi fino al 'Venusberg' e, con la disperazione nel cuore, entrerà di nuovo nel regno sotterraneo, lasciando il nostro mondo per sempre.

Una montagna e un cavaliere; un regno sotterraneo, pieno di incantamenti, dove una divinità fiabesca ha stabilito la propria dimora; un'empia permanenza tra sensuali fanciulle, dalla divina, splendente avvenenza; il rimorso e la vergogna, il timore per la propria condotta peccaminosa; la terribile visione del castigo divino; la frenetica fuga da quel luogo incantato; il tentativo di ottenere il perdono e la benedizione dal Papa di Roma.

Tutto ciò sembra condurre ad una serie di palesi, incredibili coincidenze con un altro racconto, scritto da un autore italiano nel quindicesimo secolo.

Il racconto è il "Guerrin Meschino" di Andrea da Barberino. E la montagna è il Monte Sibilla, in Italia.

Il Venusberg e il Monte Sibilla sono la stessa montagna? La leggenda di Tannhäuser è in realtà ambientata in Italia, tra i picchi vertiginosi dei Monti Sibillini? Esiste una connessione stretta, inaspettata tra la leggenda tedesca della Dama Venere e la leggenda italiana della Sibilla?

Per oltre un secolo la questione è stata affrontata da studiosi, letterati e filologi in molti libri e articoli. E la risposta è che un legame esiste: le due leggende sono sostanzialmente la stessa leggenda. E il 'Venusberg' si ergerebbe effettivamente in prossimità di Norcia.

Si tratterebbe del Monte Sibilla.

[È possibile visualizzare una versione di elevatissima qualità della bellissima miniatura raffigurante Tannhäuser contenuta nel prezioso Codice Manesse del quattordicesimo secolo (Bibliotheca Palatina di Heidelberg) qui]

17 Sep 2016

The Sibyl's peak in Italy

Mount Sibyl: the crowned mountain between Umbria and Marche. For centuries travellers coming from all countries of Europe have journeyed up to this very cliff, in search of the Sibyl's magical cave. And the name of Tannhäuser, too, had a connection to this place.

La cima della Sibilla in Italia

Monte Sibilla: la montagna coronata che si erge tra l'Umbria e le Marche. Per secoli, viaggiatori provenienti d'ogni parte d'Europa si sono diretti verso questa vetta, in cerca della magica grotta della Sibilla. E anche il nome di Tannhäuser è stato legato a questo luogo.

1 Oct 2015

Frau Venus Berg and Mount Sibyl

Tannhäuser was a German knight and minnesänger - a minstrel and a lyric poet - who was born near Salzburg in 1205. Only a few details were known about his life. Yet his name became famous owing to an incredible adventure he lived while he was wandering across Europe in the thirteenth century.

According to legend, he had chanced upon a mountain, under which the goddess Venus had settled her hidden abode after the coming of Christ into the world. After penetrating the mount, whose name was Frau Venus Berg - Mount Venus - Tannhäuser had enjoyed a full year plunged into the wicked, lustful pleasures which the goddess and her charming damsels used to bestow upon their visitors.

Incredibly enough, that was the same tale that Antoine de La Sale had narrated with reference to Mount Sibyl in Italy. Moreover, as we will see in later posts, an identical narration can be found in another old Italian chivalric romance, "Guerrino the Wretch", which recounts the deeds of another knight who crept into Mount Sibyl's cave, meeting with similar finds.

Tannhäuser and Guerrino, Germany and Italy, Frau Venus Berg and Mount Sibyl. Did a connection exist between the two legends?

The answer - of course - is positive.

Frau Venus Berg e il Monte Sibilla

Tannhäuser era un cavaliere tedesco, un minnesänger - un menestrello e poeta d'amore - nato nelle vicinanze di Salisburgo nel 1205. Solo pochi dettagli sono oggi noti a proposito della sua vita; eppure, il suo nome ha acquistato nel tempo un'enorme fama a causa dell'incredibile avventura da lui vissuta nel corso dei suoi lunghi vagabondaggi attraverso l'Europa del tredicesimo secolo.

Secondo la leggenda, egli si era imbattuto infatti in una montagna, sotto la quale la dea Venere aveva stabilito il proprio regno segreto dopo la venuta del Cristo sulla terra. Dopo essere penetrato nelle viscere della montagna, il cui nome era 'Frau Venus Berg' - il Monte di Venere - Tannhäuser aveva trascorso un anno intero immerso nei piaceri proibiti e lussuriosi che la dea e le sue bellissime damigelle erano solite regalare ai visitatori di quel reame fatato.

Quasi incredibilmente, si trattava sostanzialmente del medesimo racconto già narrato da Antoine de La Sale in riferimento al Monte della Sibilla, in Italia. Inoltre, come vedremo in altri post, un'identica narrazione può essere reperita anche in un altro antico romanzo cavalleresco, il "Guerrin Meschino", il quale racconta le vicissitudini e le gesta di un altro cavaliere, penetrato anch'egli all'interno della caverna posta sulla cima del Monte della Sibilla, nella quale era andato incontro ad avventure estremamente simili.

Tannhäuser e Guerino, Germania e Italia, Frau Venus Berg e Monte Sibilla. Esisteva forse un legame tra quelle due leggende?

La risposta è - ovviamente - positiva.

29 Sep 2015

A legendary German knight in Italy

The distinctive trait of the Italian legend of Mount Sibyl lies in the fact that its fame had spread throughout the centuries much farther than the Italian borders.

Mount Sibyl was well know across the Alps: knights and noblemen from France and Germany used to journey the Italian lands, headed to central Italy and the Sibillini Range.

They wanted to reach Mount Sibyl and the cave on the mountain-top. That happened because the legend of the Sibyl featured close and amazing links to another well-known legend: the legend of Tannhäuser, the German knight.

Un leggendario cavaliere tedesco in Italia

Il tratto distintivo della leggenda italiana del Monte Sibilla consiste nel fatto che la fama di questo mito si è diffuso per secoli ben oltre i confini dell'Italia.

Il Monte Sibilla, infatti, era ben conosciuto anche al di là delle Alpi: cavalieri e aristocratici francesi e tedeschi erano soliti recarsi in Italia, dirigendosi verso l'Italia centrale e deviando poi in direzione del massiccio dei Monti Sibillini.

Questi viaggiatori intendevano raggiungere il Monte della Sibilla e la caverna che si trovava sulla cima. Ciò accadeva perché la leggenda della Sibilla presentava strette e quasi incredibili analogie con un'altra leggenda molto nota: la leggenda di Tannhäuser, il cavaliere tedesco.