1 Nov 2017

Apennine Sibyl: the bright side and the dark side /8 “Morons of the 21st century”

We are about to conclude our series of posts on the Apennine Sibyl's bright side and dark side with an unexpected plunge into our present time, the 21st century. And you will be surprised of what can still occur in the days of science, technology and rational knowledge.

In the latest weeks, we have described the ancient tradition of a dark side marking the legend of the Apennine Sibyl, with its colourful parade of implausible demons and would-be necromancers: picturesque shadows belonging to an antique past, a suitable subject for study by modern historians interested in both folk lore and literary heritage.

Nonetheless, what would you think if you were told that someone, in our present days, still believe in such tall tales?

Incredibly enough, this is no joke: there are morons that obtusely think that the Sibillini Mountain Range is an evil place. They also believe that fiendish messages are sculpted on its largest masses of rock.

When I found it on the web, I could not believe my eyes.

These clever guys belong to a traditional catholic group, based in Brescia (northern Italy): a bunch of narrow-minded fundamentalists who are convinced that the Catholic Church is currently under attack by a coalition made up by the Enemy himself and double-dealer Popes, including Paul VI, Benedict XIV and Francis, who would be member of a covert worldwide Freemason cult determined to destroy the message of Jesus Christ on earth: as you can see, there is enough material to fill up the rooms of a dozen of asylums for mentally deranged people.

Well, the lunatics appear to hold a sort of fixation for the Sibillini Mountain Range: in their official house organ (we are not going to mention nor its title neither their website, as they do not deserve to benefit of any publicity), within issues published at the beginning of 2017, they unveil «a terrible secret that has found on the Sibillini Mountains the favourable references to be imprinted on these beautiful mountains», because - they are pretty sure of that - «the last battle Our Lady is calling on us to fight, has as a battle-ground the chain of the Sibillini Mountains and the surrounding areas».

First, they retrace the whole set of traditional mysteries connected to the Sibillini area, Guerrin Meschino, the Sibyl, the Lakes of Pilatus, the sorcerers and so on: «since ancient times», they write, «the Sibillini Mountains, have been considered magical, mysterious, occultic, and considered a destination for secret pilgrimages and blasphemous meetings between sorcerers and demons». And now it comes the moronic part: a special message from the Fiend would be inscribed in the very rock of the mountains, «the deepest and closely guarded secret of the Secret Heads of Freemasonry world-wide».

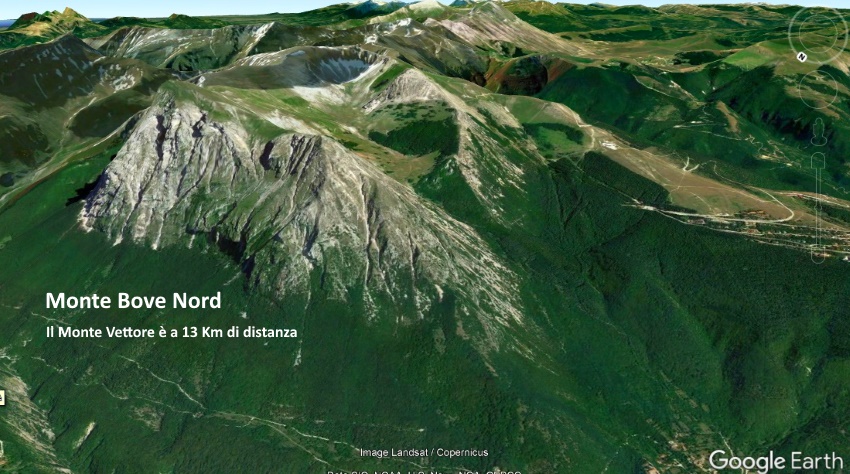

To prove their looney point, they publish a processed picture of Mount Vettore featuring superimposed satanic triangles which link the “Cima del Redentore” and the Vettore's mountain-top. They also outline a face and a body with open arms which would be 'sculpted' right on the mountain-side (see image). Additional considerations follow based on further evil triangles drawn on a map of the Sibillini Range, just as silly as the former ones.

Now a question naturally pops up in our minds: are they really stupid, or do they just pretend to be?

Because not only the whole subject is so preposterous as to be utterly ludicrous, but - in addition to that - they are so awkward as to found their crazy assumptions on the wrong picture!

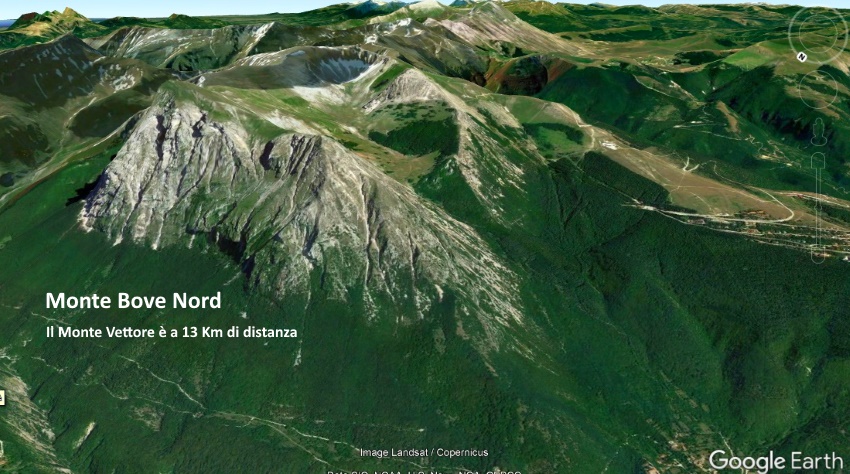

In their strenuous intellectual exertion to corroborate their idiotic fancy - an unworkable task for their inadequate brain - they actually incur a clumsy blunder: their picture DOES NOT portray the «eastern side» of Mount Vettore, as they naïvely think; instead, they unknowingly use an image of the Mount Bove North, as it can be seen when looking south-east from the area of Ussita (see image from GoogleEarth).

Of course, on the mountain-side (enlarged and zoomed in with Google Image) there is no sculpted face at all to be seen. It was just an artifact produced by their defective brain.

So their whole cogitation is mere rubbish.

We think that this is the best way to end our ride into the dark side of the Apennine Sibyl's legend: with a comparison between the historian's fascination for the ancient tales, and the asinine foolishness of Catholic fundamentalist groups (which are actually out of the Church itself).

At the very end, there is one thing we can rely upon: the Sibillini Mountain Range is an astounding, awe-striking creation of God, a breathtaking masterwork of Nature created by Him. And a reminder for all human beings that we are but small, fallible creatures. (And sometimes, as in the above case, even stupid).

Sibilla Appenninica: il lato luminoso e il lato oscuro /8 “Mentecatti del ventunesimo secolo”

Stiamo per concludere questa serie di post a proposito del lato luminoso e del lato oscuro della Sibilla Appenninica con un inaspettato tuffo nel nostro tempo presente, il 21° secolo. E sarà sorprendente vedere cosa può ancora oggi accadere in un'epoca di scienza, tecnologia e saperi razionali.

Nelle ultime settimane, abbiamo ripercorso l'antica tradizione relativa ad un lato oscuro connotante la leggenda della Sibilla Appenninica, con tutto il relativo corteggio di improbabili dèmoni e autoproclamati negromanti: ombre pittoresche appartenenti ad un remoto passato, oggi argomento di studio per il moderno storiografo interessato ad approfondire le tradizioni popolari e una lunga catena di opere letterarie.

Eppure, cosa pensereste se vi dicessero che qualcuno, nel nostro tempo attuale, crede ancora in questi assurdi racconti?

Pare incredibile, ma non si tratta affatto di uno scherzo: vi sono alcuni citrulli che ancora ritengono stupidamente che il massiccio dei Monti Sibillini sia un luogo maligno. Non solo: essi credono anche che sulle grandi masse rocciose siano inscritti messaggi diabolici.

Quando mi è capitato di reperire queste affermazioni sul web, quasi non ho potuto credere ai miei occhi.

Questi grandi intelligentoni fanno parte di un gruppo cattolico tradizionalista, con sede a Brescia: una comitiva di bigotti fondamentalisti i quali sono convinti che la Chiesa Cattolica sia attualmente oggetto di un attacco concertato da parte di una coalizione formata nientedimeno che dal Nemico in persona e da Papi doppiogiochisti, tra i quali Paolo VI, Benedetto XVI e lo stesso Francesco, i quali sarebbero tutti membri di una loggia massonica mondiale segreta determinata a cancellare il messaggio di Cristo dalla faccia della terra: come si può notare, c'è abbastanza materiale da riempire le camere di una dozzina di manicomi per gente altamente disturbata.

Bene, questi lunatici sembrano avere una sorta di fissazione per i Monti Sibillini: nella loro rivista ufficiale (non menzioneremo né il titolo né il relativo sito web, in quanto questa gente non merita il beneficio di alcuna pubblicità), tra i numeri pubblicati all'inizio del 2017, essi rivelano «un segreto terribile che ha trovato, sulla catena dei Monti Sibillini, i riferimenti favorevoli per essere impresso su queste stupende montagne», perché - loro ne sono fermamente convinti - «l’ultima battaglia alla

quale ci chiama la Madonna trova come terreno di scontro la catena dei Monti Sibillini e le aree circostanti».

Per iniziare essi citano l'intera collezione di tradizionali misteri connessi al territorio dei Sibillini, Guerrin Meschino, la Sibilla, i Laghi di Pilato, i maghi, e così via: «la catena dei

Monti Sibillini», scrivono, «sin da tempi antichissimi, è luogo magico, misterioso, considerato meta di pellegrinaggi occulti e di incontri blasfemi tra stregoni e demoni». E poi comincia la parte a maggiore concentrazione di idiozia: uno speciale messaggio del Maligno sarebbe scolpito nella viva roccia della montagna, «il segreto più profondo e gelosamente custodito dai Capi Incogniti della Massoneria mondiale».

Al fine di provare la loro balorda ipotesi, essi pubblicano un'immagine elaborata del Monte Vettore, al quale sono stati graficamente sovrapposti dei triangoli satanici che collegano la "Cima del Redentore" con la cima del Vettore. Inoltre, essi pongono in evidenza una faccia e un corpo con le braccia aperte che sarebbe 'scolpito' direttamente sul fianco della montagna (vedere immagine). Seguono poi ulteriori considerazioni, basate su nuovi triangoli tracciati su di una mappa del massiccio dei Monti Sibillini, strampalati come i precedenti.

A questo punto, sorge spontanea una domanda: ma ci sono, oppure ci fanno?

Perché non solo l'intera ipotesi è così balzana da risultare totalmente ridicola, ma - in aggiunta a ciò - i bravi ragazzi sono così goffi da fondare le loro pazzesche elucubrazioni sulla fotografia sbagliata!

Nell'inane sforzo intellettuale da essi compiuto per tentare di confermare la loro bislacca fantasia - un compito impossibile per i loro cervelli assolutamente non all'altezza - essi incorrono in un errore alquanto imbarazzante: la fotografia da loro utilizzata NON ritrae affatto il «versante orientale» del Monte Vettore, come essi ingenuamente ritengono; invece, essi stanno usando, senza saperlo, un'immagine del Monte Bove Nord, così come esso appare guardando verso sud-est dalla zona di Ussita (vedere immagine GoogleEarth).

Naturalmente, sul versante della montagna (allargato ed ingrandito usando GoogleEarth) non c'è nessuna faccia "scolpita" da osservare: si trattava solamente di un effetto ottico, generato dal loro cervellino limitato e del tutto inadeguato alla bisogna.

E così, l'intera congettura da loro elaborata risulta essere spazzatura del tipo più puro.

Pensiamo che sia proprio questo il modo migliore per concludere la nostra cavalcata attraverso il lato oscuro della leggenda della Sibilla Appenninica: con un confronto tra l'affascinato interesse dello storico per gli antichi racconti, e la sconclusionata imbecillità di un gruppo di cattolici fondamentalisti (che, comunque, sono fuori dalla Chiesa).

Alla fine di tutto, c'è una cosa della quale possiamo dirci assolutamente sicuri: il massiccio dei Monti Sibillini è una meravigliosa, stupefacente creazione di Dio, un capolavoro della Natura da Lui realizzato che ci lascia senza fiato. E un modo per ricordare a tutti gli esseri umani che siamo solo piccole, fallibili creature. (E talvolta, come nel caso qui illustrato, anche particolarmente stupide).

31 Oct 2017

Apennine Sibyl: the bright side and the dark side /7 “The beast from deep underneath”

During our long ride through the Apennine Sibyl's dark side, we have come into half-forgotten works written by Johannes Trithemius (1540), Pierre Crespet (1590) and Martino Delrio (1599): according to them, the Sibyl was a sort of subterranean demon, an evil and treacherous spirit looking for souls to snatch and luring men into unknown underground recesses by the use of beguiling illusions.

What more can we say about this highly-literary “demon”?

First, we may recall another passage from Crespetus, where he says that «it seems that the said Sibyls enjoy themselves tending sheep and lambs, and talking to herds, this being the reason for shepherds to be more acquainted with them than others»: a confirmation of the rustic character of the sibilline tradition, possibly rooted into pre-Roman times and ancient pre-Christian lore.

In the second place, Crespetus provides a further confirmation of a most remarkable fact described by a number of other authors: the cave's entrance was watched over to prevent necromancers from creeping in. Here is what Pierre Crespet reports in his book: «he [Domenico Mirabelli] added that the Pope has the cavern, where the said Sibyl lives, scrupulously guarded so at to hamper any attempt to get in contact with her; thus only sorcerers who are able to make themselves invisible can reach her». This is an official corroboration, reported by a member of the Church, that the Church itself feared the long, seemingly uninterrupted row of necromancers trying to attain the cave on the mountain-top. And we saw - from the excerpts we have read - that there were substantial reasons for concern.

However, the third and most important consideration is that «when a necromancer or other person talks to the Sibyl», says Crespetus, «storms and lightnings are stirred frightfully across the whole land». Because this sort of “subterranean demon”, as Trithemius says, «can cause wind and flames to erupt from holes in the ground. And they can shake the foundations of buildings».

They can shake the buildings from below.

Now it is clear the direct connection, or more fittingly the exact superposition, of the two legendary tales, the Sibyl's and the tradition of the Lake of Pilatus, the latter raising devastating storms when spellbooks are consecrated by its shore, as reported by Antoine de La Sale and Arnold of Harff: the cave or the lake, there is no difference between them, as in both cases the waters, the skies and the ground seem to take part in a same violent disturbance.

And such violent disturbance, such furious convulsion, which «shakes the foundations of the buildings» in a loathsome writhing of the gigantic body of the earth, a punishment for men when unholy attempts are made to address fiendish entities and attain forbidden powers - this convulsion has a name.

Its name is earthquake.

In this view, this is a further confirmation that the Apennine Sibyl's lore is nothing else than the terror dwelling in men's souls for the abominable, sudden destruction coming sometimes from deep underneath: from the mysterious, unfathomable darkness that lies beneath the Apennines.

[in Crespetus' original text: «Il dist aussi que lesdictes Sibylles prennent plaisir à garder les brebis & agneaux, & à converser aux troupeaux, qui est la raison pourquoi les bergers en ont plustot cognoissance que les autres, si est-ce que le berger qui accusa ledictes magiciens apprehendé avec eux fut estouffé par le diable en prison & trainé avec eux au supplice sur une claye tout mort pour servir de spectacle ou on devroit mettre tous ceux qui gastent & perdent les hommes, les bestes, & les champs par leurs charmes & magie.»

«Dit davantage que le Pape fait soigneusement garder la ditte carriere où est la ditte Sibylle, pour empescher la communication avec elle, & n'y a que ceux qui sont magiciens, & y peuvent invisiblement entrer qui la puissent aborder, à cause que quand on communique avec elle, soyt magicien ou autre, les tempestes & foudres s'esmouvent horriblement par tout le païs, & afin qu'on ne pense ceci estre fabuleux.»]

Sibilla Appenninica: il lato luminoso e il lato oscuro /7 “La belva dalle profondità della terra”

Nel corso del nostro lungo viaggio attraverso il lato oscuro della Sibilla Appenninica, ci siamo imbattuti nelle opere semidimenticate di Giovanni Tritemio (1540), Pierre Crespet (1590) e Martino Delrio (1599): secondo questi autori, la Sibilla era una sorta di dèmone sotterraneo, uno spirito malvagio e infido in cerca di anime da catturare e intento ad adescare gli uomini all'interno di sconosciuti recessi sotterranei, facendo uso di affascinanti illusioni.

Cosa possiamo dunque aggiungere in merito a questo "demone" così profondamente letterario?

In primo luogo, possiamo rammentare quell'ulteriore passaggio tratto da Crespeto, nel quale egli afferma che «si dice anche che le dette Sibille prendano piacere a custodire pecore ed agnelli, e a conversare con le greggi, e questa è la ragione per la quale i pastori ne avrebbero maggiore conoscenza rispetto ad altri»: una conferma del carattere pastorale della tradizione sibillina, probabilmente originatasi già in età preromana nel contesto di un sapere tradizionale precristiano.

In secondo luogo, Crespeto ci fornisce un'ulteriore conferma a proposito di un fatto di particolare importanza, già a noi noto tramite brani reperiti in altri autori: l'ingresso della caverna era sorvegliato, proprio per impedire ai negromanti di penetrare al suo interno. Ecco cosa scrive Pierre Crespet nel suo volume: «egli [Domenico Mirabelli] disse inoltre che il Papa fa attentamente sorvegliare la detta caverna dove si trova la citata Sibilla, al fine di impedire ogni comunicazione con essa, e dunque non ci sono che quei maghi in grado di rendersi invisibili che possano entrare in contatto con essa». Si tratta di una conferma ufficiale, riferitaci da un membro della Chiesa, che la Chiesa stessa temeva quella lunga ed apparentemente ininterrotta teoria di negromanti che tentavano di raggiungere la caverna sulla cima. E abbiamo visto - a giudicare dai brani che abbiamo reperito - che avevano buone ragioni per albergare tali timori.

Ma, oltre a quanto sopra menzionato, la terza e più importante considerazione è che «quando un negromante o chiunque altro entra in contatto con la Sibilla», afferma ancora Crespeto, «tempeste e fulmini si sollevano orribilmente per tutta la contrada». Perché questa tipologia di "demone sotterraneo", come aggiunge Tritemio, è «in grado di suscitare dalle fenditure della terra venti e fiamme. E scuotono le fondamenta degli edifici».

Essi possono scuotere gli edifici dal cuore della terra.

Ora è dunque chiara la connessione diretta, o più esattamente la perfetta sovrapposizione, tra i due leggendari racconti, quello relativo alla Sibilla e la tradizione concernente il Lago di Pilato, secondo la quale tempeste devastanti si sollevano quando i libri magici sono consacrati presso le sue rive, come narrato da Antoine de La Sale e Arnold di Harff: la caverna o il lago, non c'è differenza tra i due luoghi, in quanto in entrambi i casi le acque, i cieli e la terra sembrano partecipare della medesima, violentissima convulsione.

E questa terribile convulsione, questa furiosa agitazione, che «scuote le fondamenta degli edifici» con orribili contorcimenti del corpo titanico della terra - una punizione per gli uomini quando sono messi in atto empi tentativi di entrare in comunicazione con entità maligne per conseguire poteri proibiti - queste convulsioni hanno un nome.

Quel nome è terremoto.

In questo scenario, tutto ciò sembra confermare ulteriormente il fatto che il mito della Sibilla Appenninica non è niente altro che il terrore che vive nel cuore degli uomini per l'abominevole, improvvisa distruzione che risale talvolta dalle profondità degli abissi: dalla misteriosa, insondabile tenebra che giace al di sotto degli Appennini.

[nel testo originale di Crespeto: «Il dist aussi que lesdictes Sibylles prennent plaisir à garder les brebis & agneaux, & à converser aux troupeaux, qui est la raison pourquoi les bergers en ont plustot cognoissance que les autres, si est-ce que le berger qui accusa ledictes magiciens apprehendé avec eux fut estouffé par le diable en prison & trainé avec eux au supplice sur une claye tout mort pour servir de spectacle ou on devroit mettre tous ceux qui gastent & perdent les hommes, les bestes, & les champs par leurs charmes & magie.»

«Dit davantage que le Pape fait soigneusement garder la ditte carriere où est la ditte Sibylle, pour empescher la communication avec elle, & n'y a que ceux qui sont magiciens, & y peuvent invisiblement entrer qui la puissent aborder, à cause que quand on communique avec elle, soyt magicien ou autre, les tempestes & foudres s'esmouvent horriblement par tout le païs, & afin qu'on ne pense ceci estre fabuleux.»]

29 Oct 2017

Apennine Sibyl: the bright side and the dark side /6 "Crespetus and the semblance of the Sibyl"

We are now entering the gloomiest side of the legend of the Apennine Sibyl. We are approaching the dark core of it, as it has been perceived throughout hundreds of years within a contemptible milieu of soi-disant magicians and wizards, in search of an unholy entry point to personal power, riches and success, bedazzled by the lure of evil and looking for an impossible, nightmarish help to be found amid the remote peaks of the Sibillini Range.

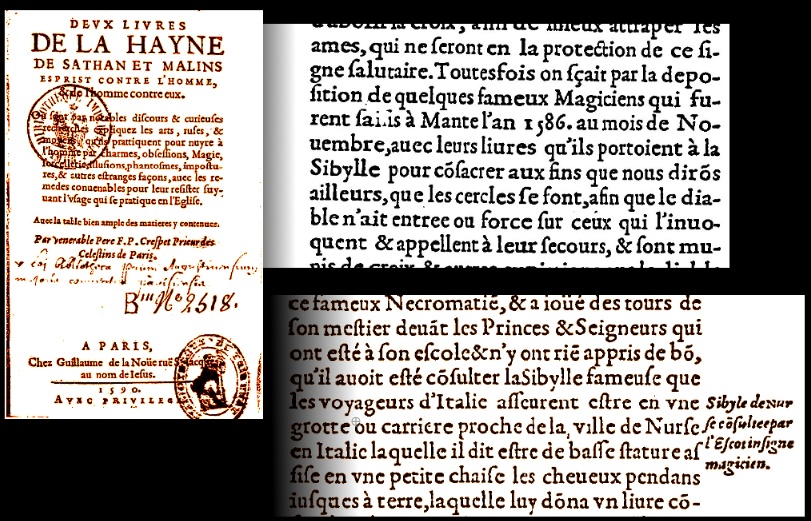

«We know through a testimony from some famed Magicians who were arrested in Mantua in the year 1586, in November, with their spellbooks that they were bringing to the Sibyl to consecrate them with the aim we mentioned before...».

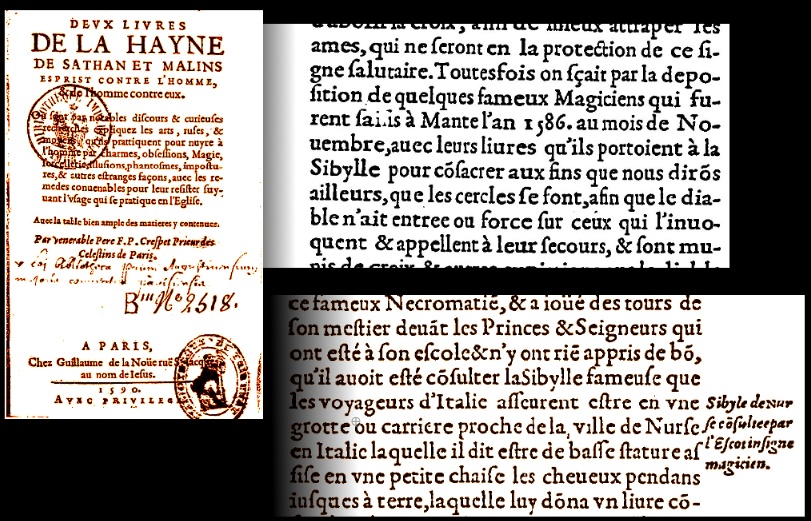

This is the astounding beginning of a previously unpublished excerpt witten by Pierre Crespet, also known as “Crespetus”, a French Celestinian monk (1543 - 1594) who had travelled across Italy to visit the monasteries of the Celestines (possibly including the one in Norcia). In his 900-hundred page treatise “De la hayne de Satan et malins esprist contro l'homme”, published in Paris in 1590, he widely speaks about the Sibyl - not any Sibyl, but exactly the Apennine Sibyl from Norcia.

Crespetus recounts a sinister occurrence, a criminal trial held in Paris against a self-styled sorcerer, who had been to Mount Sibyl in Italy: a unique document which provides the historians with a bounty of information on what the Sibyl's cave's significance was at that time.

«I don't intend to overlook a remarkable testimony drawn from a criminal trial», says Crespetus, «held against a renowned magician whose name was Domenico Mirabelli, an Italian from Arpino, and his stepmother Marguerite Garnier, who were arrested in Mantua with their spellbooks that they were fetching to the Sibyls, the goddesses of sorcerers, to consecrate them so as to render their books more powerful. The said Mirabelli testified before the judges that another associate of him, named the Scottish, who for longtime had played in France as a famed Necromancer, and used to hold tours about his craft before the Princes and Lords who had received his teachings and had learned no good lessons from them, that he went to take advice from the renowned Sibyl about whom the travellers to Italy maintain she is to be found in a cave near the town of Norcia in Italy».

Italy, Norcia, the Sibyl, the magical books, the sorcerers: all this was subject to debate before a French judge, in Paris, in 1586, under the rule of King Henri III. Seemingly, the legend of the Apennine Sibyl was being considered as an utterly sensitive issue, at least from a religious point of view, and not the least as a mere fairy tale.

Let's continue with our reading from Crespetus. The judges are questioning the Italian sorcerer. Sure enough, he is enduring excruciating tortures. The court intends to thoroughly scrutinize him so as to apprehend everything about his sinister story. And here are the words of Domenico Mirabelli, the man who said he saw the Sibyl:

«... He [Mirabelli] said she was short in stature, she was sitting in a small chair, her long hair hanging down to the ground».

The Sibyl. As she appeared to a tortured, agonizing witness, while she was sitting in her cave set amid the Italian Apennines, in the year 1586. These are the only words we can trace in centuries of literary works and essays as to the known semblance of the Apennine Sibyl.

But why sorceres and wizards were so eager to travel as far as the Sibillini Range in Italy to meet the Sibyl? Crespetus provides the answer, based on the fact that the sorcerers' wish list was right at hand, at the disposal of the judges, positively written on a sheet of paper to be handed over to the Sibyl:

«In the plea that was found on them addressed to the Sibyls who presided over Necromancy and Magic arts, the following requests were included, that they besought the Sibyls to consecrate their books so that the evil spirits shall fulfill their commanding spells without any harm for them, that they shall become visible in the form of a handsome man [...] and ready to appear at day or night, whenever conjured up. They also asked the Sibyls to mark their spellbooks, which were three in number, with their power, so that they would be able to summon the above spirits, and prevent any arrest by the Justice, and be lucky in all and every business, well received by Kings, Princes and Lords, always winners in games, and able to gather a rich wealth».

According to the testimony, Domenico Mirabelli's wishes were fulfilled: «the Sibyl gave to him a consecrated book, and into a ring he had on his finger she put a spirit; by means of these book and spirit he would be able to travel any place he wished to be transferred to, provided the wind was not blowing against him».

Thus, that's why Mount Sibyl was so renowned all across Europe. The fairy tale of a magical Sibyl, both a seer as in the romance “Guerrino the Wretch” and a powerful demon as in this gloomy report from a criminal trial, was widely known and attracted all sorts of travellers to the high peaks of the Sibillini Mountain Range.

Did the Sibyl bring luck to her visitors? Not always, and not at all in the present case. Often the applicant's personal fate did not match his own expectation, as it actually happened to Domenico Mirabelli from Arpino and his stepmother Marguerite Garnier:

«They also asked the Sibyl that the evil spirits shall not lie to them; however, they were all the same convicted and sent to the stake and burnt in Paris together with their books, so that everyone shall know that the devil is a true cheater & enchanter, & all who associate with him are heathens, and sentenced».

How many of such self-appointed wizards have been coming to Mount Sibyl, across many centuries, to ask for the same forbidden services? In the next post, we will probe furher into Crespetus' words and find many significant connections to the legend of the Lake of Pilatus and other legendary tales.

[In the original Latin text (Livre I, Discours 15): «Toutesfois on sait par la deposition de quelques fameux Magiciens qui furent saisis à Mante l'an 1586, au mois de Novembre, avec leurs livres qu'ils portoient à la Sibylle pour consacrer aux fins que nous dirons ailleurs, que les cercles se font, afin que le diable n'ait entree ou force sur ceux qui l'invoquent & appellent à leur secours, & sont munis de croix & autres expiations que le diable redoubte. Car en la requeste qu'on leur trouva pour presenter au Sibylles qui president sur la Necromance, & Magie, ces choses estoient contenues, qu'ils supplioient les Sibylles de consacrer leur livres à tels effects que les mauvais esprits fissent tout ce que leur seroit enjoint par leur coniuration sans faire aucun mal, apparoissans en forme de bel homme, & qu'on ne fust contrainst de faire aucun cercle n'y en leurs maisons, ny aux champs, & qu'ils fussent prompts à venir de nuist & de jour, quand ils seroient evoquez. Les supplioient aussi d'apposer à leurs dits livres de Magie, qui estoient trois en nombre, leur caractere, afin qu'ils eussent plus de puissance pour appeller lesdits esprits, & qu'ils ne fussent repris de Iustice, ains qu'ils fussent fortunez en toutes leurs entreprises, bien aymez des Roys Princes, & grands Seigneurs, ne perdissent jamais aux jeux, ains fussent chanceux & gaignassent quand ils voudroient, que leurs ennemis ne pourtassent nuysance [...] à la charge aussi que les mauvais esprits ne seroient point menteurs, mais ils furent condamnez, au feu & bruslez à Paris avec leurs livres, afin qu'on sache que le diable est vrai trompeur & seducter, & tous ceux qui luy adherent sont Idoatres & reprouvez.»]

[In the original Latin text (Livre I, Discours 6): «Je ne veux obmettre un notable discours tiré d'un procés qui a esté fait d'un insigne magicien nommé Dominique Mirabille Italien natif d'Arpine & à sa belle mere Marguerite Garnier, qui furent apprehendez à Mante avec leur livres de magie qu'ils portoient aux Sibylles deesses des magiciens pour etre consacrez, à fin d'avoir plus d'effet comme j'ay dit ailleurs, ledit Mirabille deposa devant les juges qu'un autre sien compagnon nommé l'Escot qui a long temps rodéen France fameux Necromantie, & a joué des tours de son mestier devant les Princes & Seigneurs qui ont esté à son escole & n'y ont rien appris de bon, qu'il avoit esté consulter la Sibylle fameuse que les voyageurs d'Italie asseurent etre en une grotte ou carriere proche de la ville de Nurse en Italie la quelle il dit estre de basse stature assise en une petite chaise les cheveux pendans jusque à terre, laquelle luy donna un livre consacré, & luy meit dans un agneau qu'il avoit au doigt un esprit, par le moyen desquels livre & esprit il eust la puissance d'aller en tous lieux où il souhaittoit estre transporté moyenant que le vent ne fust contraire.»]

Sibilla Appenninica: il lato luminoso e il lato oscuro /6 "Crespeto e le sembianze della Sibilla"

Stiamo per fare ingresso negli aspetti più oscuri della leggenda della Sibilla Appenninica. Ci stiamo approssimando sempre di più al cuore tenebroso del mito, così come recepito lungo centinaia e centinaia di anni in un contesto poco raccomandabile composto da sedicenti maghi e incantatori, alla ricerca di un sacrilego punto di accesso al potere personale, alla ricchezza e al successo, abbagliati dalle seduzioni del male e in cerca di un aiuto impossibile, da reperirsi, come in un incubo, tra i picchi remoti dei Monti Sibillini.

«Sappiamo attraverso la testimonianza di alcuni famosi Incantatori i quali furono catturati a Mantova nell'anno 1586, nel mese di Novembre, con i loro libri magici che essi stavano portando alla Sibilla per consacrarli per i fini che abbiamo in precedenza illustrato...».

È questo l'incredibile principio di un brano mai pubblicato in precedenza, scritto da Pierre Crespet, conosciuto anche come "Crespetus", un monaco celestiniano di origine francese (1534 - 1594) che aveva viaggiato attraverso l'Italia per visitare i monasteri appartenenti alla Congregazione dei Celestini (incluso forse quello situato a Norcia). Nel suo trattato "De la hayne de Satan et malins esprist contro l'homme", lungo ben 900 pagine e pubblicato a Parigi nel 1590, egli ci parla estesamente della Sibilla - e non di una Sibilla qualsiasi, ma proprio della Sibilla Appenninica di Norcia.

Crespeto ci presenta una narrazione alquanto sinistra: un processo penale tenuto a Parigi contro un sedicente incantatore, che si era recato in Italia al Monte della Sibilla: un documento unico, in grado di fornire allo storico una significativa messe di informazioni sull'importanza della Grotta della Sibilla a quell'epoca.

«Non ometterò di riferire a proposito di un significativo discorso tratto da un processo che fu fatto contro un famoso mago chiamato Domenico Mirabello, italiano nativo di Arpino, e contro la sua matrigna Marguerite Garnier, i quali furono entrambi arrestati a Mantova con i loro libri di magia, che essi stavano portando alle Sibille, divinità dei maghi, per essere consacrati, al fine di potenziarli come ho già spiegato. Il detto Mirabello depose innanzi ai giudici affermando che un altro suo compagno chiamato lo Scotto, che aveva per lungo tempo agito in Francia come famoso Negromante, e aveva posto in scena delle dimostrazioni della sua arte davanti a Principi & Signori che erano stati alla sua scuola, e nulla di buono ne avevano appreso, che egli era stato a consultare la famosa Sibilla che i viaggiatori in Italia affermavano trovarsi in una grotta o cava in prossimità della città di Norcia in Italia».

L'Italia, Norcia, la Sibilla, i libri magici, gli incantatori: tutto questo è stato oggetto di dibattito innanzi ad un giudice francese, a Parigi, nel 1586, regnante il Re Enrico III. Il mito leggendario della Sibilla Appenninica era evidentemente considerato come un argomento estremamente sensibile, quantomeno da un punto di vista religioso, e per nulla da derubricarsi come una mera, vuota favola.

Continuiamo con la nostra lettura tratta da Crespeto. I Giudici stanno interrogando il mago di origine italiana. Certamente, egli è sottoposto a terribili torture. La Corte ha intenzione di esaminarlo approfonditamente per verificare ogni dettaglio di questa sinistra vicenda. Ed ecco dunque le parole di Domenico Mirabelli, l'uomo che afferma di avere veduto la Sibilla:

«... Egli [Mirabelli] disse che la Sibilla era di bassa statura, seduta su di una piccola sedia, i lunghi capelli sciolti fino a terra».

La Sibilla. Così come era apparsa ad un testimone torturato, forse agonizzante; la Sibilla, seduta nella sua caverna posta tra le cime dell'Appennino italiano, nell'anno 1586. Sono queste le sole parole, pervenuteci attraverso secoli di saggi e opere letterarie, che descrivano le sembianze osservate della Sibilla Appenninica.

Ma perché maghi e incantatori si mostravano così bramosi di recarsi fino ai lontani Monti Sibillini, in Italia, per incontrare la Sibilla? Crespeto ci fornisce la risposta, grazie al fatto che la lista dei desideri di quei negromanti era lì a portata di mano, a disposizione dei giudici, vergata in modo manifesto su di un foglio di carta destinato ad essere consegnato alla stessa Sibilla:

«Nella richiesta che venne loro trovata indosso, da presentarsi alle Sibille che presiedevano alla Negromanzia e alla Magia, erano contenute queste cose, che essi supplicavano le Sibille di consacrare i loro libri in modo tale che gli spiriti maligni facessero tutto ciò che fosse loro ingiunto nel corso dell'evocazione senza loro nuocere, apparendo in piacevole forma di uomo [...] e che fossero pronti a venire di notte come di giorno, quando fossero stati evocati. Le supplicavano inoltre di apporre ai loro libri magici, che erano in numero di tre, il proprio marchio, affinché essi risultassero più potenti al fine di poter richiamare i detti spiriti, e che essi non fossero mai arrestati dalla Giustizia, e anche che risultassero favoriti in tutte le loro imprese, amati sommamente da Re, Principi e grandi Signori, che non perdessero mai ai giochi d'azzardo, e potessero anche godere della fortuna e guadagnare quanto volessero».

Secondo il testimone, i desideri di Domenico Mirabelli furono effettivamente esauditi: «la Sibilla gli diede un libro consacrato, & mise in un anello che egli aveva al dito uno spirito, per mezzo dei quali libro e spirito egli avrebbe avuto il potere di recarsi in ogni luogo egli avesse desiderato di essere trasportato, a condizione che il vento non gli fosse contrario».

Dunque, ecco perché il Monte della Sibilla raggiunse una fama di tale portata attraverso l'Europa intera. Il racconto fiabesco di una Sibilla magica, una veggente, come nel romanzo "Guerrin Meschino", ma anche un potente dèmone come in questo fosco resoconto tratto da un processo penale, era ampiamente noto ed in grado di attrarre ogni sorta di viaggiatori fino agli elevati picchi del Massiccio dei Monti Sibillini.

Era capace, la Sibilla, di donare fortuna ai propri visitatori? Non sempre, e di certo non nel presente caso. Spesso, il destino personale del supplice non si conformava alle aspettative che il medesimo desiderava, come in effetti accadde a Domenico Mirabelli da Arpino e alla sua matrigna Marguerite Garnier:

«Essi chiesero anche alla Sibilla che gli spiriti non mentissero loro; ma essi furono comunque condannati, gettati nel rogo & bruciati a Parigi assieme ai loro libri, affinché si sappia che il demonio è il vero ingannatore e seduttore, e che tutti coloro che si associano ad esso sono Idolatri, e saranno puniti».

Quanti di questi sedicenti maghi si sono recati fino al Monte Sibilla, nel corso di così tanti secoli, per implorare gli stessi, proibiti servigi? Nel prossimo post, analizzeremo più approfonditamente le parole di Crespeto, rilevando alcune significative connessioni con il mito del Lago di Pilato e altri racconti leggendari.

[Nel testo originale francese (Livre I, Discours 15): «Toutesfois on sait par la deposition de quelques fameux Magiciens qui furent saisis à Mante l'an 1586, au mois de Novembre, avec leurs livres qu'ils portoient à la Sibylle pour consacrer aux fins que nous dirons ailleurs, que les cercles se font, afin que le diable n'ait entree ou force sur ceux qui l'invoquent & appellent à leur secours, & sont munis de croix & autres expiations que le diable redoubte. Car en la requeste qu'on leur trouva pour presenter au Sibylles qui president sur la Necromance, & Magie, ces choses estoient contenues, qu'ils supplioient les Sibylles de consacrer leur livres à tels effects que les mauvais esprits fissent tout ce que leur seroit enjoint par leur coniuration sans faire aucun mal, apparoissans en forme de bel homme, & qu'on ne fust contrainst de faire aucun cercle n'y en leurs maisons, ny aux champs, & qu'ils fussent prompts à venir de nuist & de jour, quand ils seroient evoquez. Les supplioient aussi d'apposer à leurs dits livres de Magie, qui estoient trois en nombre, leur caractere, afin qu'ils eussent plus de puissance pour appeller lesdits esprits, & qu'ils ne fussent repris de Iustice, ains qu'ils fussent fortunez en toutes leurs entreprises, bien aymez des Roys Princes, & grands Seigneurs, ne perdissent jamais aux jeux, ains fussent chanceux & gaignassent quand ils voudroient, que leurs ennemis ne pourtassent nuysance [...] à la charge aussi que les mauvais esprits ne seroient point menteurs, mais ils furent condamnez, au feu & bruslez à Paris avec leurs livres, afin qu'on sache que le diable est vrai trompeur & seducter, & tous ceux qui luy adherent sont Idoatres & reprouvez.»]

[Nel testo originale francese (Livre I, Discours 6): «Je ne veux obmettre un notable discours tiré d'un procés qui a esté fait d'un insigne magicien nommé Dominique Mirabille Italien natif d'Arpine & à sa belle mere Marguerite Garnier, qui furent apprehendez à Mante avec leur livres de magie qu'ils portoient aux Sibylles deesses des magiciens pour etre consacrez, à fin d'avoir plus d'effet comme j'ay dit ailleurs, ledit Mirabille deposa devant les juges qu'un autre sien compagnon nommé l'Escot qui a long temps rodéen France fameux Necromantie, & a joué des tours de son mestier devant les Princes & Seigneurs qui ont esté à son escole & n'y ont rien appris de bon, qu'il avoit esté consulter la Sibylle fameuse que les voyageurs d'Italie asseurent etre en une grotte ou carriere proche de la ville de Nurse en Italie la quelle il dit estre de basse stature assise en une petite chaise les cheveux pendans jusque à terre, laquelle luy donna un livre consacré, & luy meit dans un agneau qu'il avoit au doigt un esprit, par le moyen desquels livre & esprit il eust la puissance d'aller en tous lieux où il souhaittoit estre transporté moyenant que le vent ne fust contraire.»]

27 Oct 2017

Apennine Sibyl: the bright side and the dark side /5 "Martino Delrio and the illusions de Specu Nursino"

Let's continue our journey into the dark side of the Apennine Sibyl's legend and lore: the black heart of a tradition which for centuries has conveyed European sorcerers and necromancers all the way to a remote mountainous land in Italy, the Sibillini Range.

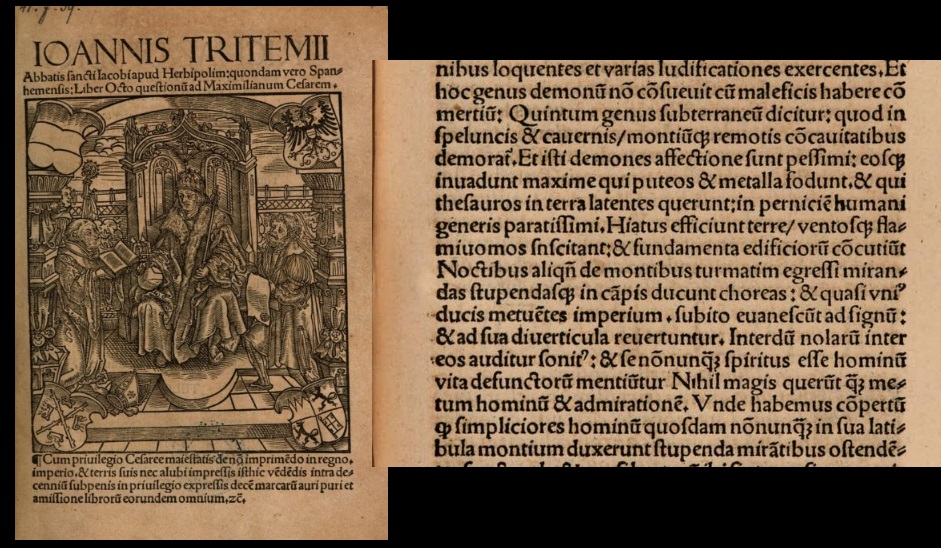

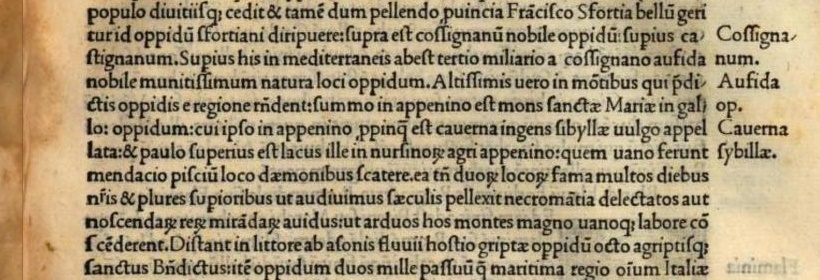

In a previous post, we saw that in 1540 Johannes Trithemius introduced a ranking of evil spirits, among which he defined a class of mean “subterranean demons”.

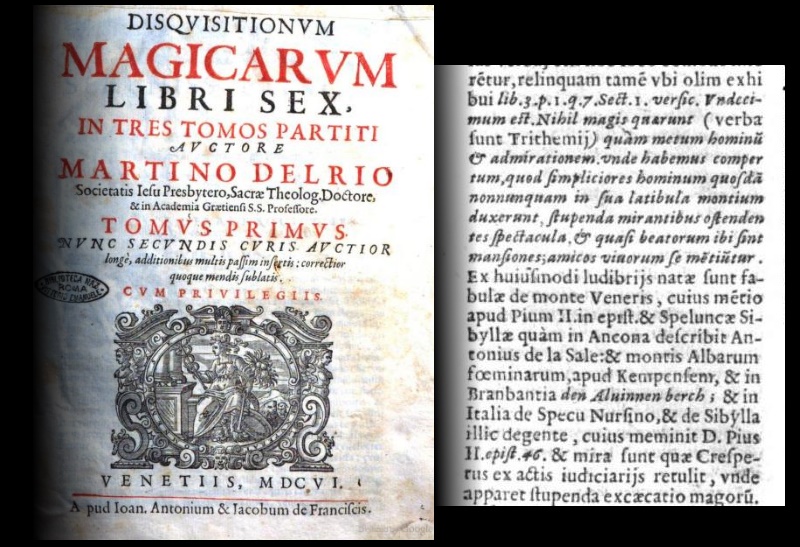

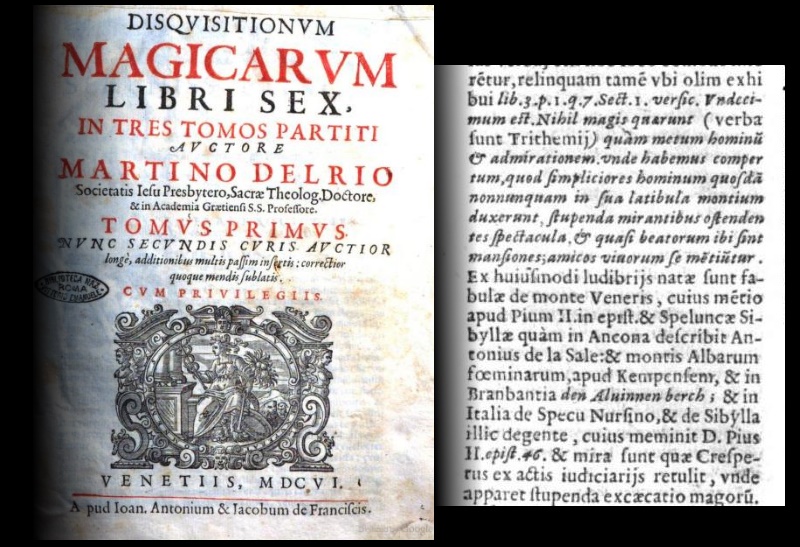

Anything to do with the Apennine Sibyl? Yes indeed. It will be Martino Delrio, a Flemish priest who lived in the second half of the sixteenth century and was member of the Society of Jesus, who will place our Sibyl right into Trithemius' fifth category dedicated to underground fiends.

Delrio wrote a ponderous treatise on black magic and sorcery, the “Disquisitionum magicarum libri sex”, published in 1599. In Book II, under Question 27 relating to evil apparitions, he reviews in detail the classification set by Trithemius. When it comes to the fifth class, he quotes Trithemius's words about the malicious habit of subterraean demons to lure people «down into their hidden recesses under the mounts to show them splendid illusory images». And here is what he writes next:

«It is from such guiles that the fairy tales about Mount Venus arise, which is mentioned in a letter written by Pope Pius II and in the description of a Sibyl's Cavern placed in the region of Ancona as reported by Antoine de la Sale; in addition to that, we also have a mount of the White women near Kempenfent and the “She-Elf mount” in the Netherlands; and in Italy the cave lying near Norcia with a Sibyl living in it, as recorded by Pius II in his letter n. 46».

So the Apennine Sibyl - the same entity described by Antoine de la Sale in his “Paradise of Queen Sibyl” and whose cave was also referred in a letter written by a fifteenth-century Pope (we will see it in a subsequent post) - became officially enrolled in a not-so-glorious troop of malicious demons: an evil spirit of the netherworld, associated to the fabled “mountains of Goddess Venus”, the mounts of enchanted love, of which a number of tales were told in many northern-European countries (one of those tales was that of Tannhäuser).

With Martino Delrio, the dark side of the Apennine Sibyl, dating back at least to two centuries earlier, was becoming apparent in the cultural debate on magic between the sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries.

Everybody - including disreputable people interested in black arts, and the Church as well - now knew that in the mountains of Norcia was to be found a cave which was the abode of some kind of supernatural being: a "hot spot", where a crevice in our material world afforded an entry point to an eerie, unearthly, uncanny world.

And Martino Delrio provides further information on that. He quotes from another author, whose name is “Crespetus”. And this Crespetus, as referred by Delrio, says that someone had actually the incredible, extraordinary chance to meet the Sibyl: a personal, direct encounter with the Apennine Sibyl of Norcia. This person had seen the actual semblance of the fiendish Sibyl.

Who was Crespetus? What did he wrote exactly? And who was the mortal man who met the legendary Apennine Sibyl?

The answers to such astonishing questions will be presented in the next post of “The Apennine Sibyl - A Mystery and a Legend”. Stay tuned!

[in the original Latin text: «Ex huiusmodi ludibriis natae sunt fabulae de monte Veneris, cuius mentio apud Pium II in epistola et Speluncae Sibyllae quam in Ancona decsribit Antonius de la Sale; et montis Albarum foeminarum apud Kempenfent, et in Branbantia 'den Alvinnen berch'; et in Italia de Specu Nursino et de Sibylla illic degente, cuius meminit D. Pius II [in] epistola 46...»]

Sibilla Appenninica: il lato luminoso e il lato oscuro /5 "Martino Delrio e le illusioni de Specu Nursino"

Continuiamo il nostro viaggio attraverso il lato oscuro della leggenda della Sibilla Appenninica: il cuore tenebroso di una tradizione che, per secoli, ha esercitato una incredibile capacità di attrazione su maghi e negromanti di tutta Europa, fino ad una remota regione montuosa situata al centro dell'Italia, i Monti Sibillini.

In un precedente post, abbiamo visto come nel 1540 Giovanni Tritemio avesse introdotto una classificazione degli spiriti maligni, tra i quali egli aveva definito uno specifico sottogruppo di malvagi "demoni del sottosuolo".

Che relazione poteva avere tutto questo con la Sibilla Appenninica? Un legame, in effetti, molto stretto. Sarà infatti Martino Delrio, un sacerdote fiammingo vissuto nella seconda metà del sedicesimo secolo, membro della Compagnia di Gesù, che posizionerà la nostra Sibilla direttamente all'interno della quinta classe di Tritemio dedicata ai demoni sotterranei.

Delrio aveva compilato un ponderoso trattato sulla magia nera, il “Disquisitionum magicarum libri sex”, pubblicato nel 1599. Nel Libro II, alla Questione 27 relativa alle maligne apparizioni, egli ripercorre in dettaglio la classificazione definita da Tritemio. Giunto alla quinta classe, Delrio riporta il passo di Tritemio nel quale si parla della sinistra abitudine dei demoni sotterranei di adescare gli uomini «fino ai segreti recessi delle loro montagne, mostrando loro meravigliose illusioni». Ed ecco cosa scrive subito dopo:

«È proprio da questi inganni che sono si sono originate le favole a proposito del monte di Venere, di cui si fa menzione nella lettera di Papa Pio II e nella descrizione della Grotta della Sibilla nella regione di Ancona riportata da Antoine de la Sale; e anche della montagna delle femmine Bianche vicino Kempenfent, e del 'monte delle Donne elfiche' nel Brabante; e in Italia a proposito della Caverna di Norcia e della Sibilla che lì risiederebbe, della quale fece menzione Pio II nell'epistola 46».

E così, la Sibilla Appenninica - la stessa entità descritta da Antoine de la Sale nel suo "Paradiso della Regina Sibilla", la cui caverna era stata menzionata anche in una lettera quattrocentesca scritta da Papa Pio II (la vedremo in un prossimo post) - era stata ufficialmente arruolata tra i ranghi ingloriosi di un esercito di malvagi dèmoni: uno spirito maligno dell'oltretomba, associato alle favolose "montagne della dèa Venere", i monti dell'amore incantato, in merito ai quali venivano raccontate molte storie soprattutto nei Paesi del nord Europa (e uno di questi racconti era quello di Tannhäuser).

Con Martino Delrio, il lato oscuro della Sibilla Appenninica, già resosi apparente almeno due secoli prima, diviene manifesto nell'ambito del dibattito culturale in corso sulla magia tra i secoli sedicesimo e diciassettesimo.

Tutti, ma proprio tutti - compresi certi equivoci personaggi interessati alle arti magiche, e la stessa Chiesa - sono ora informati del fatto che tra le montagne di Norcia si trova una caverna, nella quale abiterebbe un qualche genere di essere soprannaturale: un "punto caldo", dove una fessurazione nel nostro mondo materiale rende possibile il passaggio verso un mondo spirituale sinistro e terrifico.

E Martino Delrio non si trattiene dal fornirci ulteriori informazioni su questo tema. Egli cita da un altro autore, il cui nome è "Crespeto". E questo Crespeto, come riferitoci da Delrio, afferma che qualcuno avrebbe avuto l'incredibile, straordinaria possibilità di incontrare la Sibilla: un incontro diretto e personale con la Sibilla Appenninica di Norcia. Questa persona avrebbe addirittura potuto contemplare le sembianze della demoniaca Sibilla.

Chi era Crespeto? Che cosa aveva scritto esattamente? E chi era quell'uomo mortale che aveva potuto incontrare la leggendaria Sibilla Appenninica?

Le risposte a queste stupefacenti domande saranno presentate nel prossimo post di "Sibilla Appenninica - Il Mistero e la Leggenda". Restate collegati!

[nel testo originale latino: «Ex huiusmodi ludibriis natae sunt fabulae de monte Veneris, cuius mentio apud Pium II in epistola et Speluncae Sibyllae quam in Ancona decsribit Antonius de la Sale; et montis Albarum foeminarum apud Kempenfent, et in Branbantia 'den Alvinnen berch'; et in Italia de Specu Nursino et de Sibylla illic degente, cuius meminit D. Pius II [in] epistola 46...»]

21 Oct 2017

Apennine Sibyl: the bright side and the dark side /4 "Johannes Trithemius and the subterranean demon"

The legend of the Apennine Sibyl: a fairy tale, a mysterious journey, a chivalric dream of adventure and bravery, or even a silly narrative for simpletons and dupes. That's the bright side of it.

However, there is also a dark side. A tale of magic and witchcraft, deceptive illusions and black arts. Ever since the tales of Guerrino the Wretch and Antoine de La Sale were told, the Apennine Sibyl has presented herself as an evil spirit, in search of souls to snatch and capable of transforming herself into loathsome snakes.

The Sibyl's dark side was actually well known all across Europe, as attested in many quotes drawn from all centuries and countries.

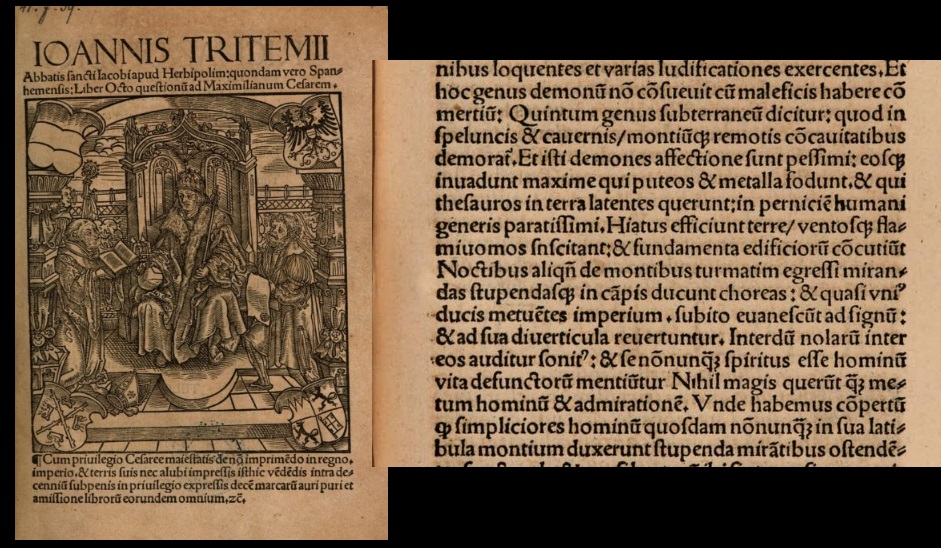

To understand the reason for the Sibyl's dark renown, we have to go to back to the roots of magical culture in the Renaissance age, and namely to Johannes Trithemius, a German Benedictine abbot who lived between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and became a leading figure within a long-lasting tradition in the mysterious and the occult.

In his work “Liber octo questionum ad Maximilianum Cesarem”, a series of answers to questions put to him by Emperor Maximilian I, published in 1540, he dedicates the sixth answer (“Questio sexta”) to the power of black magic (“De potestate maleficarum”). In this section he provides a ranking scheme of fiendish demons according to the very spots where they originally happened to fall from heaven at the beginning of the world.

A specific class is devoted to the “genus subterraneum”, the evil spirits who fell into the underground regions of the earth:

«The fifth kind is called subterranean: they are the ones who reside in caverns and caves and hollows placed under remote peaks. The power of such demons is utterly evil: they especially seize those who dig tunnels to search metallic ore, and those who look for treasures hidden under the ground. They are most willing to harm human beings. They can cause wind and flames to erupt from holes in the ground. And they can shake the foundations of buildings».

What has it to do with the Apennine Sibyl? Let's see the subsequent excerpt and we will find further resemblances to our legend:

«At night, multitudes of them use to leave their dens in the mountains to perform the most amazing, spectacular dances in the fields: they vanish at once under the command of one of them whose authority they fear, and rush back into their subterranean trails. Sometimes small bells can be heard tinkling among their ranks».

This strongly reminds us of the dancing fairies with goat-like feet that descended at night from Mount Vettore, according to local traditional lore in the Sibillini area. And there is more to it:

«They ask for nothing more than raise terror and awe in the heart of men», continues Trithemius. «We know that at times they lead simple, gullible people down into their hidden recesses under the mountains to show them splendid illusory images, as if down there would lie the abode of blessed souls. [...]

This is the most striking correspondence with the legend of the Apennine Sibyl: the magical, underground kingdom full of palaces and treasures, in the perfect bliss of an eternal life and the love of handsome damsels. Yet it is just an evil illusion, a deceptive trick played on men by a subterranean demon.

Just a groundless misinterpretation of the Apennine Sibyl's lore? Not at all. Because we can retrieve a further mention to all this in a book written in the subsequent century.

And this book, whose author is Martino Delrio, a Flemish Jesuit, will explicitly enroll the Apennine Sibyl within Trithemius' fifth class: nothing more and nothing less than a recognized “subterranean demon”.

[in the original Latin text: «Quintum genus subterraneum dicitur: quod in speluncis et cavernis montiumque remotis concavitatibus demorant. Et isti daemones affectione sunt pessimi: eosque invadunt maxime qui puteos & metalla fodunt, & qui thesauros in terra latentes querunt: in pernicie humani generis paratissimi. Hiatus efficiunt terrae ventosque flaminomos suscitant: & fundamenta edificiorum concutiunt. Noctibus aliquu de montibus turmatim egressi mirandas stupendasue in campis ducunt choreas: & quali uni ducis metuentes imperium, subito evanescunt ad signum: & ad sua diverticula revertuntur. Interdum nolarum inter eos auditur sonit [...] Nihil magis querunt quam metum hominum & admirationem. Unde habemus compertum quod simpliciores hominum quosdam nonnumquam in sua latibula montium duxerunt stupenda mirantibus ostendentes spectacula: et quasi beatorum ibi sint mansiones amicos se virorum mentiuntur.»]

Sibilla Appenninica: il lato luminoso e il lato oscuro /4 "Giovanni Tritemio e il demone sotterraneo"

La leggenda della Sibilla Appenninica: un racconto fiabesco, un viaggio nel mistero, un sogno cavalleresco di avventura e ardimento, o anche una sciocca narrazione per sempliciotti e creduloni. Questo è il lato luminoso del mito.

Esiste, però, anche un lato oscuro. Un racconto di magia e incantesimi, di ingannevoli illusioni e arti tenebrose. Fin da quando furono narrati per la prima volta i racconti di Guerrin Meschino e Antoine de La Sale, la Sibilla Appenninica si è presentata come uno spirito maligno, in cerca di anime delle quali impossessarsi e capace di trasformare se stessa in disgustosi serpenti.

Questo lato oscuro della Sibilla era ben conosciuto in tutta Europa, come attestato dalle numerose citazioni rinvenibili in tutti i secoli e presso tutti i paesi.

Per comprendere la ragione di questa fosca nomea, dobbiamo ritornare alle radici della cultura magica rinascimentale, e in particolare a Giovanni Tritemio, un abate benedettino di origine tedesca vissuto a cavallo tra il quindicesimo e il sedicesimo secolo, divenuto uno dei più importanti esponenti di una lunga tradizione connessa allo studio dell'occulto e del mistero.

Nella sua opera "Liber octo questionum ad Maximilianum Cesarem”, una serie di risposte a domande postegli dall'Imperatore Massimiliano I, pubblicata nel 1540, Tritemio dedica la sesta risposta ("Questio sexta") al potere della magia nera (“De potestate maleficarum”), definendo una classificazione dei dèmoni sulla base dei luoghi presso i quali essi si trovarono a cadere originariamente dal cielo al principio del mondo.

Una classe specifica è dedicata al “genus subterraneum”, e cioè a quegli spiriti maligni che, dal cielo, sprofondarono fino alle regioni sotterranee della terra:

«Il quinto genere è chiamato sotterraneo: coloro che dimorano nelle spelonche e caverne e cavità delle remote montagne. E questi dèmoni sono estremamente pericolosi: si impadroniscono specialmente di coloro che scavano gallerie e cercano metalli, e di chi è alla ricerca di tesori nascosti sotto la terra: sono particolarmente desiderosi di nuocere al genere umano. Essi sono inoltre in grado di suscitare venti e fiamme dalle fenditure della terra. E scuotono le fondamenta degli edifici».

Ma cosa ha a che fare, tutto questo, con la Sibilla Appenninica? Andiamo a leggere il passo successivo, andando a trovare nuove interessanti corrispondenze con la nostra leggenda:

«Talvolta, di notte, escono in moltitudini dalle montagne e inscenano danze meravigliose e spettacolari nei campi, per poi subitamente sparire al comando di uno di loro, di cui temono l'imperio, ritornando così nei loro nascondigli sotterranei. Qualche volta è anche possibile udire, tra le loro schiere, il suono tintinnante di campanelli».

Tutto ciò non può non riportarci alla mente le fate danzanti con piedi caprini che scendevano di notte dal Monte Vettore, secondo la nota tradizione locale viva nell'area dei Monti Sibillini. Ma c'è ancora qualcosa di più:

«Essi non chiedono di meglio che suscitare terrore e stupefazione nel cuore degli uomini. È noto inoltre che in alcuni casi essi abbiano condotto uomini tra i più semplici fino ai segreti recessi delle loro montagne, mostrando loro meravigliose illusioni: come se ivi fossero da trovarsi le aule degli uomini beati».

Si tratta di un'interessantissima corrispondenza con la leggenda della Sibilla Appenninica: il magico regno sotterraneo, ricolmo di palazzi e tesori, nella gioia perfetta di una vita eterna da viversi nell'amore di affascinanti damigelle. Ma è solo un'illusione malefica, un trucco ingannevole giocato agli uomini da un dèmone del sottosuolo.

Potrebbe trattarsi di un'infondata, equivoca interpretazione del mito della Sibilla Appenninica? La risposta è che non c'è nulla di infondato. Perché siamo in grado di reperire un'ulteriore menzione, riferita a quanto qui sopra illustrato, all'interno di un altro volume scritto nel secolo successivo.

E questo libro, il cui autore è Martino Delrio, un gesuita fiammingo, arruolerà esplicitamente la Sibilla Appenninica nella quinta classe di Tritemio: nulla di più e nulla di meno di un accreditato "demone sotterraneo".

[nel testo originale latino: «Quintum genus subterraneum dicitur: quod in speluncis et cavernis montiumque remotis concavitatibus demorant. Et isti daemones affectione sunt pessimi: eosque invadunt maxime qui puteos & metalla fodunt, & qui thesauros in terra latentes querunt: in pernicie humani generis paratissimi. Hiatus efficiunt terrae ventosque flaminomos suscitant: & fundamenta edificiorum concutiunt. Noctibus aliquu de montibus turmatim egressi mirandas stupendasue in campis ducunt choreas: & quali uni ducis metuentes imperium, subito evanescunt ad signum: & ad sua diverticula revertuntur. Interdum nolarum inter eos auditur sonit [...] Nihil magis querunt quam metum hominum & admirationem. Unde habemus compertum quod simpliciores hominum quosdam nonnumquam in sua latibula montium duxerunt stupenda mirantibus ostendentes spectacula: et quasi beatorum ibi sint mansiones amicos se virorum mentiuntur.»]

20 Oct 2017

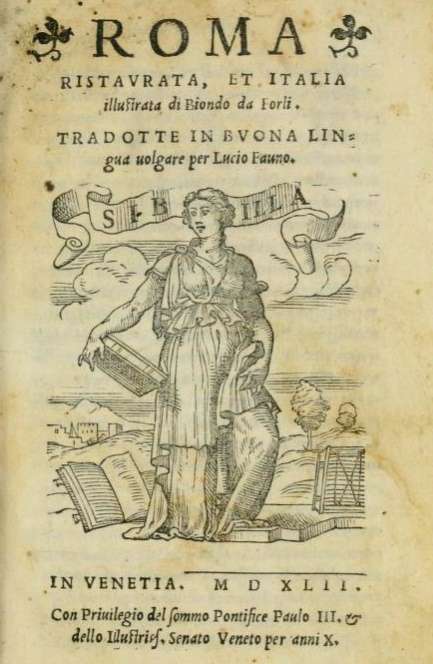

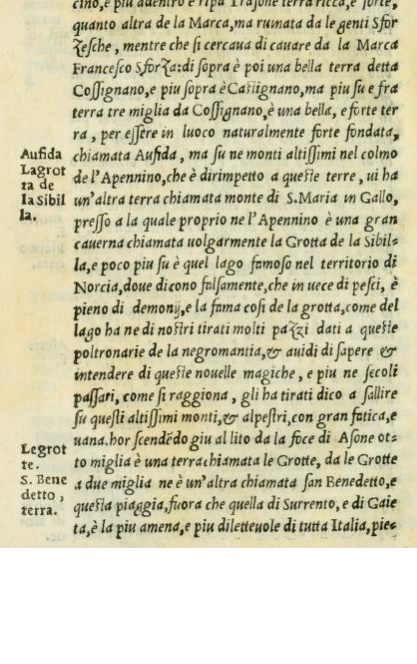

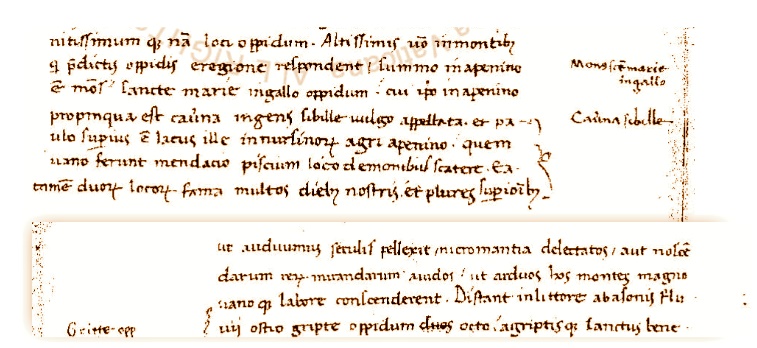

Apennine Sibyl: the bright side and the dark side /3 "Flavio Biondo and such foolish thing as necromancy"

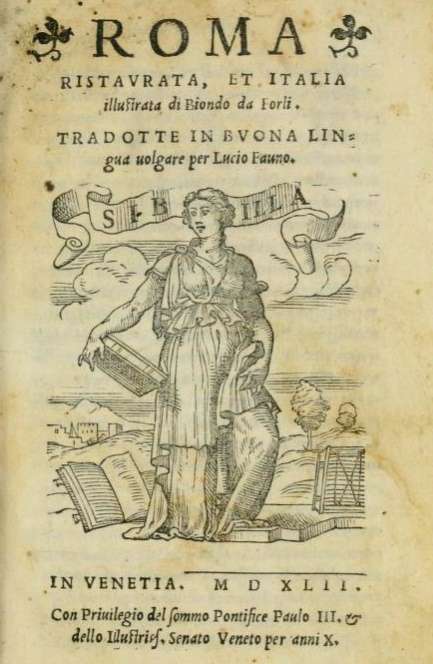

An author who did not express any appreciation for the legend of the Apennine Sibyl was Flavio Biondo, an Italian historian who lived in the first half of the fifteenth century and was a forerunner of modern archeology.

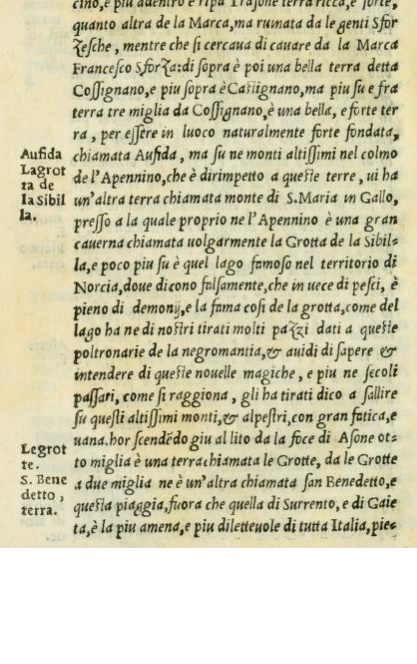

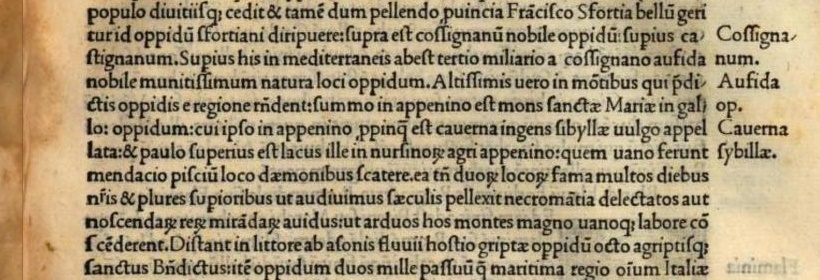

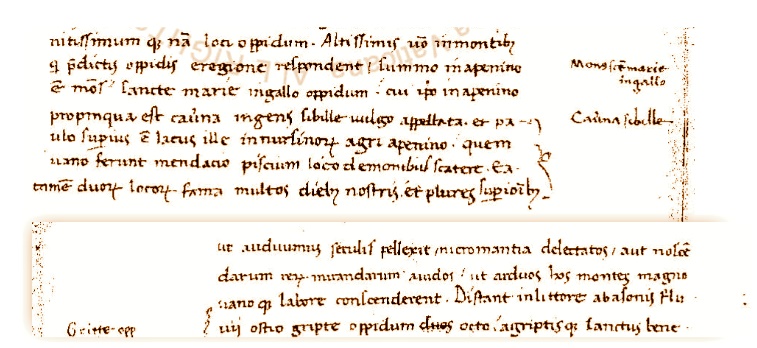

In his “Italia illustrata” (“Italy illustrated”), published in 1474 in Latin and subsequently translated into Italian in 1542, he dedicated a few words to our Sibyl, showing no inclination at all for what he seems to consider a dull tale:

«Up amid the towering mountains at the very centre of the Apennines, facing the land we've just been talking about, there is another land whose name is S. Mary in Gallo, in the vicinity of which - in the very heart of the Apennines - is a huge cavern called 'the Sibyl's cave” by the populace; further above, in the territory of Norcia, there is that renowned lake where according to false rumours the waters would be replete of evil spirits rather than fish; and the fame of both the cavern and the lake has attracted a great number of lunatics committed to such foolish thing as necromancy, in search of knowledge and understanding of those sorcerous teachings; and a lot more in past centuries, as is reported, they were lured up to those lofty, imposing mountains, with great exertion, and utterly in vain».

Thus, many prominent men of letters - though including the Sibyl's cave and lake in their literary works, for the mere sake of completeness - regarded the two legendary tales as silly accounts which might be of interest only for dummies and candid simpletons.

However, not all people in Europe thought the same. Some of them took the Sibyl's cave, and lake, very seriously. Dead seriously. For they did not disdain to practice what Biondo had marked with the words «such foolish thing as necromancy».

And - as we will see in the next post - they weren't people you would have liked to have business with.

[in the pictures, a unique collection of Flavio Biondo's “Italy illustrated” editions:

- a charming print of a Sibyl on the cover of 1542's Italian translation by Lucio Fauno

- the excerpt on the Apennine Sibyl from the 1542 Italian edition

- the excerpt on the Apennine Sibyl from the original 1474 Latin edition

- never published before: the same excerpt from the original manuscript written by Flavio Biondo (Ottobonian Latin n. 2369 from the Vatican Apostolic Library)]

Sibilla Appenninica: il lato luminoso e il lato oscuro /3 "Flavio Biondo e le poltronarìe de la negromantia"

Un altro autore del tutto contrario ad esprimere apprezzamento nei confronti della leggenda della Sibilla Appenninica è Flavio Biondo, il grande storico, nonché antesignano della moderna archeologia, vissuto nella prima metà del quindicesimo secolo.

Nella sua "Italia illustrata", pubblicata in lingua latina nel 1474 e successivamente tradotta in italiano nel 1542, Biondo dedica poche righe alla nostra Sibilla, mostrando chiaramente di non provare alcuna inclinazione verso quella che egli reputava essere una sciocca dicerìa:

«Su nei monti altissimi nel colmo de l'Apennino, che è dirimpetto a queste terre, vi ha un'altra terra chiamata di S. Maria in Gallo, presso a la quale proprio ne l'Apennino è una gran caverna chiamata volgarmente la Grotta de la Sibilla, e poco più su è quel lago famoso nel territorio di Norcia, dove dicono falsamente, che in vece di pesci, è pieno di demoni, e la fama così de la grotta, come del lago ha ne di nostri tirati molti pazzi dati a queste poltronarìe de la negromantia, et avidi di sapere et intendere di queste novelle magiche, e più ne secoli passati, come si raggiona, gli ha tirati dico a sallire su questi altissimi monti, et alpestri, con gran fatica, e vana».

E così, molti rinomati uomini di lettere - benché disposti ad includere menzioni della caverna sibillina e del lago all'interno delle proprie opere letterarie, per mero scrupolo di completezza - consideravano i due racconti leggendari come stupide favole, tali da poter essere di interesse solamente per ignoranti e sempliciotti.

Eppure, non tutti, in Europa, la pensavano così. Alcuni personaggi prendevano la caverna della Sibilla e il lago molto sul serio. Tremendamente sul serio. Gente che non disdegnava di praticare quelle che il Biondo aveva definito le «poltronarìe de la negromantia».

E - come vedremo nel prossimo post - non si trattava certo di persone con il quale sarebbe stato piacevole avere a che fare.

[nelle immagini, una raccolta unica delle edizioni dell'”Italia illustrata” di Flavio Biondo:

- una pregevole stampa raffigurante una Sibilla sul frontespizio della traduzione in lingua italiana del 1542 curata da Lucio Fauno

- il brano sulla Sibilla Appenninica tratto dall'edizione in lingua italiana del 1542

- il brano sulla Sibilla Appenninica tratto dall'edizione in lingua latina del 1474

- mai pubblicato in precedenza: il medesimo brano tratto dal manoscritto originale scritto da Flavio Biondo (Ottoboniano Latino n. 2369 conservato presso la Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana)]

19 Oct 2017

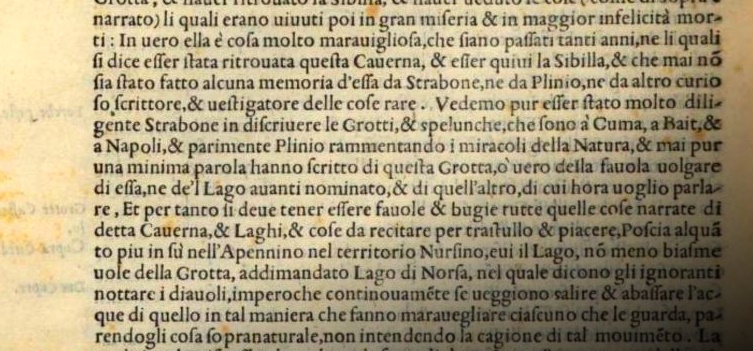

Apennine Sibyl: the bright side and the dark side /2 "When I was a small child"

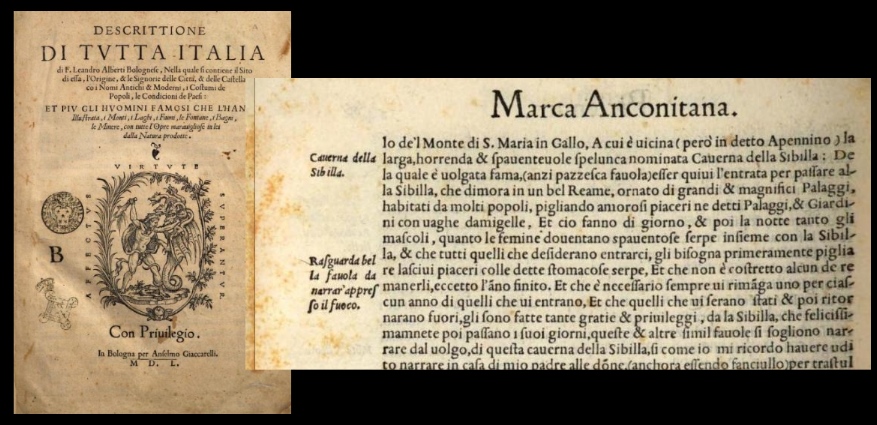

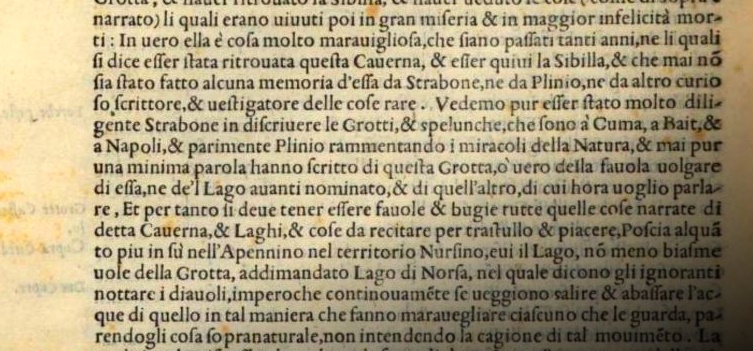

If we look for an author of past centuries providing no endorsement to the Apennine Sibyl's lore, we need to address Dominican friar Leandro Alberti. As anticipated in our previous post, he shows no reluctance when it comes the time to demolish the illustrious myth. And his style of writing takes on a hue of playful mockery:

«It comes as a bit of a surprise that so many years have elapsed, from the time when this Cavern was discovered and saluted as the Sibyl's abode, and no mention of it has ever been recorded at all, neither in the works by Strabo nor in Pliny's nor in the writings of any other inquisitive Author, in search of oddities and rarities. And yet every reader can consider by himself how scrupulously Strabo has provided a full description of the Caves and hollows that are to be found in Cuma, and Baiae, and Naples; and Pliny, as well, has written most accurate reports of the many wonders of Nature; however, no one of them ever wrote a single word about that Cavern, nor provided any accounts as regards the cave's folk tale [...]. In conclusion, all such tales being told about the said Cavern must be regarded as fables, and mere lies, an enjoyable narrative to be delivered to a thrilled and delighted audience».

And that's not all. He reports the quite humorous tale of the «learned and pragmatic Germans» who journeyed as far as the renowned Lakes of Pilatus «at their own significative expense» to consecrate their spellbooks to the evil spirits - totally nonexistent - so that they found themselves «downright cheated» and were forced to retrace their own steps to Germany «cursing both themselves and their fellow-men, the latter for circulating such foolish tales, the former for having placed their trust in them so naively».

«I am convinced», finally writes Alberti, with a jeering, scornful understatement, «that not much

time has passed since the rumour about that Cavern has spread […]. For if the cave had been really known in antiquity, there is no doubt that its finding would have been duly recorded, as actually was the case for the Oracle at Delphi, and Podalirius, and Avernus, and the Hollow and Cave of the said Cumæan Sibyl, and many other places likewise, as well as caverns, Lakes, Trees, Rivers, Springs, Woods, Temples, Altars and further Oracles of the same kind, where evil Spirits are said to utter deceitful words to beguile men».

That's how Leandro Alberti, a man of wit and experience, turns down the legend of a Sibyl in the Apennines. It is the year 1550 and Alberti has just stated the words that will become the fundamental, still unsettled historical issue in our contemporary research on the Apennine Sibyl: her obscure, enigmatic lineage from classical Sibyls and the lack of any literary reference in authors from ancient Rome.

However, the only concession made to the myth by the knowledgeable writer is not an insignificant one: it is actually a tribute to the might of the Sibyl's legend, to the power of a fairy tale.

Alberti, too, was fascinated and bewitched by the legendary tale. He was but a child, and we can imagine his eyes open wide as he used to listen to the timeless tale of the Apennine Sibyl:

«Such fairy tales, and the like are told by the peasants about the Sibyl's cave, as I myself happened to hear in my father's house, when I was a small child, for the thrilled entertainment of women».

Despite all his sharp, rational reasoning, he too had been enveloped by the magical spell of the Sibyl.

Sibilla Appenninica: il lato luminoso e il lato oscuro /2 "Anchora essendo fanciullo"

Se fossimo in cerca di un autore dei secoli passati del tutto intenzionato a non sottoscrivere i racconti relativi alla Sibilla Appenninica, dovremmo rivolgerci al frate domenicano Leandro Alberti. Come anticipato nel nostro precedente post, infatti, il nostro storico e geografo non mostra di provare alcuna remora quando si tratta di demolire l'illustre leggenda. E il suo stile di scrittura diviene addirittura giocosamente ironico:

«In vero ella è cosa molto maravigliosa, che siano passati tanti anni, ne li quali si dice esser stata ritrovata questa Caverna, & esser quivi la Sibilla, & che mai non sia stato fatto alcuna memoria d'essa da Strabone, ne da Plinio, ne da altro curioso scrittore, & vestigatore delle cose rare. Vedemo pur esser stato molto diligente Strabone in discrivere le Grotti, & spelunche, che sono a Cuma, a Baia, & a Napoli, & parimente Plinio rammentando i miracoli della Natura, & mai pur una minima parola hanno scritto di quella Grotta, ò vero della favola volgare di essa [...] Et per tanto si deve tener essere favole & bugie tutte quelle cose narrate di detta Caverna, & Laghi, & cose da recitare per trastullo & piacere».

E questo non è tutto. L'Alberti riporta anche quel racconto, ridicolmente divertente, a proposito di quei «Thedeschi huomini dotti & pratici» che decidono di spingersi fino ai famosi Laghi di Pilato, «con gran spesa», per consacrare i loro libri magici ai dèmoni lacustri - del tutto immaginari - e ritrovandosi così «uccellati», e costretti a riprendere il cammino del ritorno verso la natìa Germania «maledicendo se & gli altri, questi per haver divolgate queste favole, & se per haverle tanto facilmente credute».

«Credo non esser molto tempo», prosegue ancora l’Alberti, con perfidia velata, dissacrante, «che siano state volgate queste favole di detta Caverna […]. Perché se fossero stati osservati dagli antiqui, non dubito che ne sarebbe stato fatto memoria, sicome e fatto dell’Oracolo di Delpho, di Podalirio, dell’Averno, & dell’Antro, & Spelunca della detta Sibilla Cumea, & parimente de molti altri luoghi, sicome di spelunche, Laghi, Alberi, Fiumi, Fontane, Selve, Tempii, Sacelli, & simili altri Oracoli, ove davano risposta i bugiardi Demonii per ingannare gli huomini».

Ecco dunque come Leandro Alberti, uomo di grandissima esperienza e intelligenza, distrugge infine la leggenda di una Sibilla tra gli Appennini. Correva l'anno 1550 e Alberti ha appena enunciato le parole che costituiranno il maggior problema storico, ancor oggi irrisolto, della ricerca contemporanea sulla Sibilla Appenninica: la sua oscura, enigmatica discendenza dalle Sibille classiche e la mancanza di qualsivoglia menzione letteraria negli autori di Roma antica.

Eppure, l'unica concessione che l'esperto scrittore si permette di accordare al mito non è di poco momento: si tratta, infatti, di un tributo alla potenza della leggenda sibillina, al potere del sogno e della favola.

Anche Leandro Alberti, in effetti, era rimasto colpito e affascinato da quel racconto leggendario. A quell'epoca non era che un bambino, e noi possiamo oggi immaginare i suoi occhi meravigliati e spalancati, mentre quel bimbo ascoltava ancora una volta il racconto senza tempo della Sibilla Appenninica:

«Queste & altre simil favole si sogliono narrare dal volgo, di questa caverna della Sibilla, si come io ricordo havere udito narrare in casa di mio padre alle donne, (anchora essendo fanciullo) per trastullo & piacere».

Malgrado tutta la sua fredda, logica razionalità, anche lui era stato reso prigioniero dal magico incanto della Sibilla.

18 Oct 2017

Apennine Sibyl: the bright side and the dark side /1 "Leandro Alberti and the popular lore"

The myth of an Apennine Sibyl has crossed many centuries, arousing the interest and fascination of very different people all around Europe.

During its long journey, the legend has been the subject for a wide range of literary speculations. Among the plethora of quotes from a multitude of authors, we are going to highlight two special subsets of them: the excerpts written by those who scorned the accounts about the Apennine Sibyl as a silly tale for simpletons and morons; and - on the other side - the quotes from people we wouldn't like to meet at a solitary corner in the middle of the night: people who practised forbidden arts, and thought the Sibyl's legend was everything but a mockery.

Let's begin with one of the most skeptical descriptions of the Sibyl's lore ever written: an excerpt by Leandro Alberti, a Dominican friar who lived in the sixteenth century and was the author of a most renowned historical and geographical work, “The General description of Italy”, dating to year 1550.

Alberti starts his description by depicting the magnificent, imposing nature of the Sibillini Mountain Range:

«[...] where the Apennine is much elevated. Here is the area which divides the Picenum region from the mountains of Norcia: and in actual truth, above the place where Arquata lies, the Apennine raises to such a degree that it exceeds itself in elevation, in other words it overtakes all remaining adjacent peaks despite their considerable elevation. This is the reason why this mount is called Vettore».

The Dominican friar was a brilliant spirit, a man of learning and a talented preacher; so when it comes to the queer tales of the Sibyl's cave and the nearby lake, he is not easily convinced at all:

«On the portion of this towering mountain facing eastward, it can be seen that most famous Lake of which tales are told about the conjuring of devils summoned by sorcerers, who would speak to them. If such accounts were true, it would certainly deserve severe condemnation, and such witchcrafts should be hardly punished under both Canonical and Imperial laws: I believe those are but fairy tales and lies, as I will show later in my book when describing the Sibyl's Cave».

And here the cavern comes, a grim, forbidding place in its appearance, yet clad with what Leandro Alberti considered to be but silly tales:

«The lofty Apennine mountains are seen in this region, on one of those peaks stands the Castle of St. Mary in Gallo. Nearby, namely in the said Apennine, lies the huge, frightful, ghastly hollow which was named after the Sibyl: about which a popular lore (or rather a foolish rumour) maintains that it provides admittance to the realm of the Sibyl, who would be living in a beautiful Kingdom, adorned with magnificent Palaces, where many people would reside, enjoying themselves with lustful pleasures within the said Palaces and Gardens together with handsome maids...»

In the next post, we will see how the Dominican friar continues to depict the cavern and its fame: a renown which used to attract all sort of fools up to the very core of the Sibillini Range.

Sibilla Appenninica: il lato luminoso e il lato oscuro /1 "Leandro Alberti e la volgata fama"

Il mito della Sibilla Appenninica ha attraversato molti secoli, destando in tutta Europa l'affascinato interesse di personaggi estremamente differenti tra di loro.

Nel corso del suo lunghissimo viaggio, la leggenda è stata oggetto di una vasta molteplicità di speculazioni letterarie. Tra la grande varietà di citazioni rinvenibili in moltissimi autori, andremo a porre in evidenza due sottogruppi particolari: i brani scritti da coloro i quali respingevano e quasi deridevano i racconti che venivano narrati a proposito della Sibilla Appenninica, in quanto stupide favole per sempliciotti e creduloni; e - dall'altro lato - le citazioni tratte da personaggi che non gradiremmo incontrare in una strada poco frequentata nel bel mezzo della notte: gente che praticava arti proibite, e pensava che la leggenda della Sibilla potesse essere tutto tranne che uno scherzo.

Cominciamo allora con una delle descrizioni relative alla tradizione sibillina maggiormente improntata allo scetticismo: un brano tratto da Leandro Alberti, un frate dominicano vissuto nel sedicesimo secolo, autore di un'opera storico-geografica di grande fortuna, la "Descrittione di tutta l'Italia", pubblicata nel 1550.

Alberti comincia la propria descrizione illustrandoci tutta la magnificenza e l'imponenza dei Monti Sibillini:

«[...] ove è molto alto esso Appennino. Quivi si partisse questa parte de'l Piceno da i monti de i Norsini: Vero è che sopra quel luogo ove è Arquata, tanto si alza l'Apennino, che se istesso se supera in altezza, cioè che avanza tutti gli altri suoi continouati gioghi siano di quanta altezza possono. Et per tanto è addimandato questo monte Vettore. Quivi è partito il territorio Piceno da'l Norsino».

Il frate domenicano era un uomo brillante, un erudito e un predicatore di grande esperienza; così, quandi si tratta di considerare le strane favole che si narrano attorno alla Grotta della Sibilla e al vicino lago, egli non si lascia affatto convincere:

«Vedesi alla parte de quest'altissimo monte, (che riguarda all'oriente) quel tanto famoso Lago de'l quale se dice che vi appareno i demoni costretti dagli incantatori, & che qui vi parlano con essi. Che se così fusse sarebbe cosa molto biasimevole, & tali incantamenti meriterebbero gravissime punitioni secondo le leggi Canoniche & Imperiali: Io credo che siano tutte favole e menzogne, come poi dimostrerò descrivendo la Grotta della Sibilla».

Ed ecco la descrizione della grotta, luogo spaventevole nella sua oscura, formidabile apparenza, rivestita però di ciò che Leandro Alberti stigmatizzava come sciocche dicerìe:

«Veggionsi in questo paese gli altissimi monti dell'Appennino, sopra uno de li quali appare edificato il Castello de'l Monte di S. Maria in Gallo. A cui è vicina (però in detto Apennino) la larga, horrenda & spaventevole spelunca nominata Caverna della Sibilla: De la quale è volgata fama, (anzi pazzesca favola) esser quivi l'entrata per passare alla Sibilla, che dimora in un bel Reame, ornato di grandi & magnifici Palaggi, habitati da molti popoli, pigliando amorosi piaceri ne detti Palaggi, & Giardini con vaghe damigelle...».

Nel prossimo post, vedremo come Leandro Alberti continuerà a riportare notizia della grotta e della sua fama: una rinomanza che pareva attirare ogni sorta di sprovveduti sin lassù, fin nello sperduto cuore dei Monti Sibillini.