16 Jul 2018

A Sibyl called Cimmerian: exploring the potential link to the Apennine Sibyl - 12. The path towards the true origin of the sibilline myth

We made a long journey throughout the centuries in search of the fourth Sibyl, the Cimmerian. We started from Francesco Maurolico, a sixteenth-century Sicilian abbot, and we went as far back as Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius and other classical Latin and Greek authors including Silius Italicus, Sextus Pompeius Festus, Pliny the Elder, Lycophrone of Chalcis, Sextus Aurelius Victor, Publius Vergilius Maro, St. Justin Martyr and Strabo. We have perused the works of Andrea da Barberino, Filippo Barbieri, the Muslim astronomer Albumazar, the fifteenth-century “Oracula Sibyllina”, and excerpts from later authors such as Juan Luis Vives, Michel Antoine Baudrand and Cesare Orlandi.

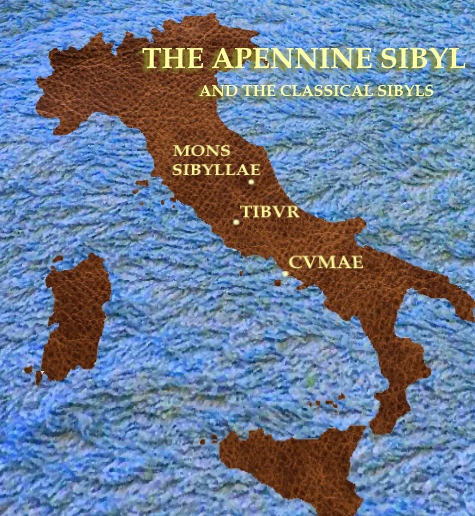

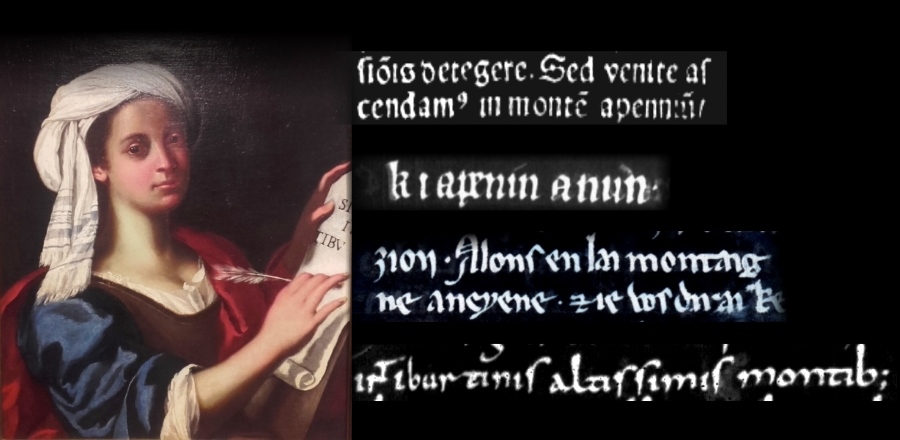

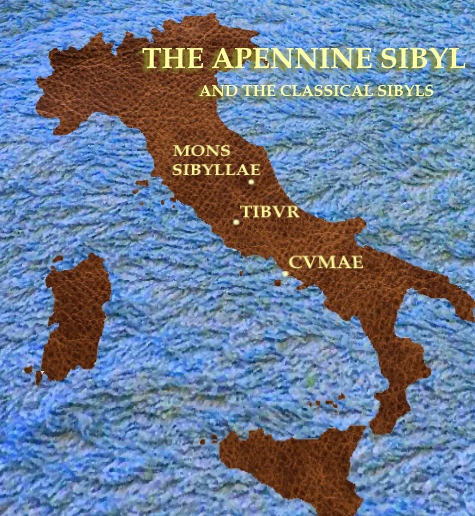

We have demonstrated that all the clues which refer to the Cimmerian Sibyl lead to Cumae, in the Italian province of Campania. Only abbot Francesco Maurolico seems to depart from this unanimous view, as he alone asserts that the fourth Sibyl, the Cimmerian, is in truth the Apennine Sibyl of Norcia.

At the present stage of our search, we do not have any clue as to why Maurolico (and apparently only Maurolico) holds such a belief. We could not retrieve any other earlier literary source conveying the same idea.

However, some pattern begins to appear amid the literary works, excerpts, passages, and mentions providing references to the world of the sibilline oracles: the Apennine Sibyl seems to present some kind of veiled, undeciphered connection to the Cumaean / Cimmerian Sibyl, as assumed by Andrea da Barberino in his fifteenth-century romance “Guerrino the Wretch” and Francesco Maurolico in his “Topographia”.

That is, some cryptic link is apparently arising between the Apennines, set in the vicinity of Norcia, and Cumae.

We still don't know what this relation might be. Better than that, we already hold a specific idea on this highly fascinating subject, but this idea is still untold. An obscure surmise which “The Apennine Sibyl - A Mystery and a Legend” will reconsider and develop in future articles, not yet published.

For the time being, we are leaving the reader with the suggestions connected to the ancient, long-vanished town of the Cimmerians, with all its mysterious spell that has bewitched men of letters of all times. A mystery we have tried to shed light upon, by walking the narrow paths traced by many authors of essays, romances and poems throughout many centuries.

An arcane travel which we want to conclude with the words written by the greatest poet of all, Homer, in his epic poem “Odyssey”. There, in Book 11, he speaks of the gloomy mystery of the Cimmerians:

«She [Odysseus' ship] came to deep-flowing Oceanus, that bounds the Earth, where is the land and city of the Cimmerians, wrapped in mist and cloud. Never does the bright sun look down on them with his rays either when he mounts the starry heaven or when he turns again to earth from heaven, but baneful night is spread over wretched mortals».

Odysseus lands «to the place of which Circe had told us»: «the house of Hades», where he performs the most frightful of all rites, the summoning of the dead from the Underworld, a gloomy ritual known as 'nekya'.

The Apennine Sibyl, the Cumaean Sibyl, the Cimmerian Sibyl, the Underworld. A legendary mystery that appears to be rooted in the deepest recesses of time, and human mind.

Una Sibilla chiamata Cimmeria: un'investigazione sulla possibile relazione con la Sibilla Appenninica - 12. Il cammino verso la vera origine del mito sibillino

Abbiamo compiuto un lungo viaggio attraverso i secoli alla ricerca della quarta Sibilla, la Cimmeria. Siamo risaliti da Francesco Maurolico, un abate siciliano vissuto nel sedicesimo secolo, fino a Lucio Cecilio Firmiano Lattanzio e ad altri autori latini e greci della classicità, tra i quali Silio Italico, Sesto Pompeo Festo, Plinio il Vecchio, Licofrone di Calcide, Sesto Aurelio Vittore, Publio Virgilio Marone, San Giustino Martire e Strabone. Abbiamo consultato i volumi di Andrea da Barberino, di Filippo Barbieri e dell'astronomo islamico Albumazar, e poi i quattrocenteschi "Oracula Sibillina" e brani tratti da autori più recenti quali Juan Luis Vives, Michel Antoine Baudrand e Cesare Orlandi.

Abbiamo dimostrato come tutti gli indizi connessi alla Sibilla Cimmeria conducano a Cuma, nella regione italiana della Campania. Solamente l'abate Francesco Maurolico pare distaccarsi da questa visione del tutto unanime, in quanto egli solo asserisce come la quarta Sibilla, la Cimmeria, sia in realtà la Sibilla Appenninica di Norcia.

Allo stadio attuale della nostra ricerca, non possiamo stabilire per quale motivo Maurolico (e, in tutta apparenza, solamente Maurolico) attesti questa posizione. Non è stato per noi possibile rintracciare alcuna ulteriore, e precedente, fonte letteraria che sostenga questa medesima idea.

Eppure, una flebile traccia sembra apparire tra le opere, i brani, i passaggi e le citazioni che si riferiscono al mondo degli oracoli sibillini: la Sibilla Appenninica pare presentare un qualche tipo di velato, indecifrabile collegamento con la Sibilla Cumana / Cimmeria, così come attestato da Andrea da Barberino nel romanzo quattrocentesco "Guerrin Meschino" e da Francesco Maurolico nella propria "Topographia".

In altre parole, una qualche sorta di nesso indistinto, enigmatico si starebbe delineando tra gli Appennini, che si ergono in prossimità di Norcia, e Cuma.

Ancora non sappiamo in cosa possa consistere esattamente questa relazione. O, meglio, abbiamo già una specifica idea in merito a questa tematica così altamente affascinante, ma questa idea è ancora inespressa. Un'ipotesi oscura, che "Sibilla Appenninica - Il Mistero e la Leggenda" ha intenzione di approfondire e sviluppare in futuri articoli, non ancora pubblicati.

Per il momento, vogliamo lasciare il lettore con le suggestioni legate all'antica città, da lungo tempo perduta, dei Cimmèri, con tutto il suo fascino misterioso e arcano, in grado di avvincere poeti e letterati di ogni epoca. Un mistero sul quale abbiamo tentato di gettare luce, percorrendo gli stretti sentieri tracciati da una pluralità di autori di saggi, romanzi e poemi nel corso di molti secoli.

Un viaggio arcano che vogliamo concludere con le parole scritte dal più grande poeta di ogni tempo, Omero, nella sua "Odissea". Qui, nel Libro 11, egli così ci racconta del tenebroso mistero dei Cimmèri:

«Essa [la nave di Ulisse] ai confini arrivò dell'Oceano corrente profonda, là dei Cimmèri è il popolo e la città, di nebbia e nube avvolti. Mai su di loro il sole splendente guarda coi raggi, né quando sale verso il cielo stellato, né quando verso la terra ridiscende dal cielo, ma notte tremenda grava sui mortali infelici».

Ulisse approda «al luogo che indicò Circe»: «la casa dell'Ade», presso cui egli effettua il più spaventoso dei riti, l'evocazione dei morti dall'Oltretomba, la cosiddetta 'nekya'.

Sibilla Appenninica, Sibilla Cumana, Sibilla Cimmeria, il mondo sotterraneo dei morti. Un mistero leggendario che pare trovare le proprie origini nei più nascosti recessi del tempo, e della mente umana.

15 Jul 2018

A Sibyl called Cimmerian: exploring the potential link to the Apennine Sibyl - 11. It's a long way from the Cimerian Sibyl to the Apennines

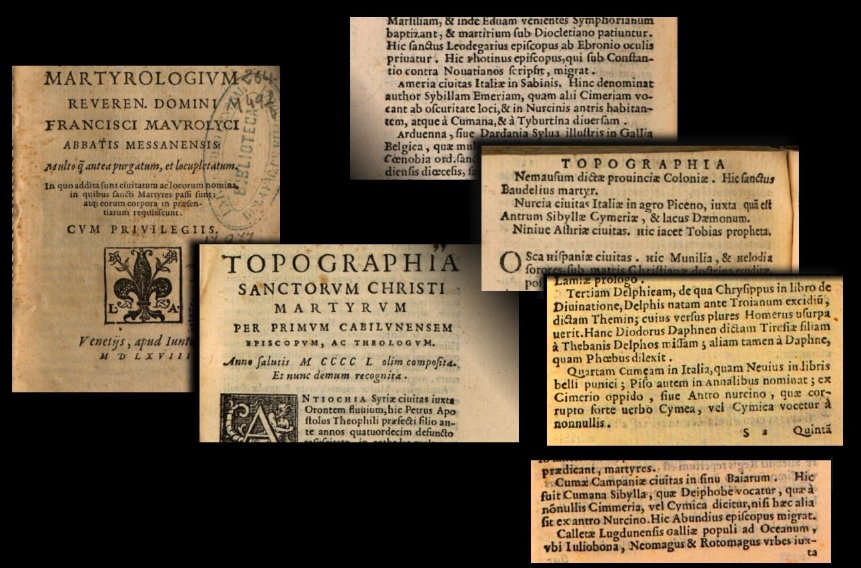

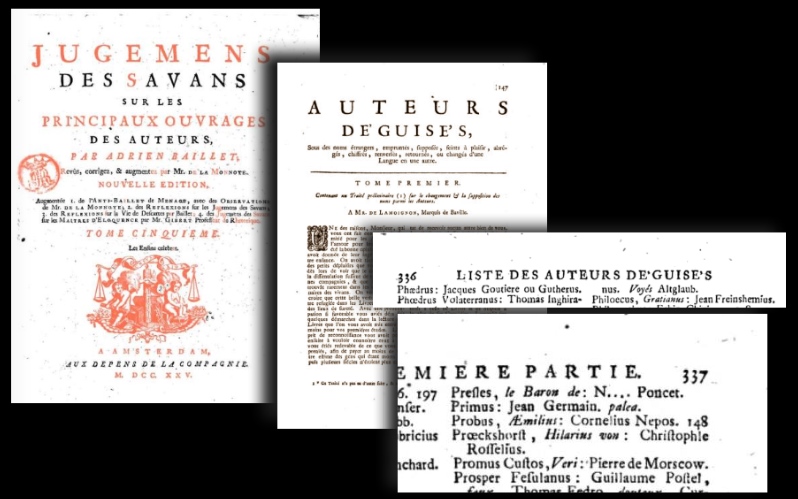

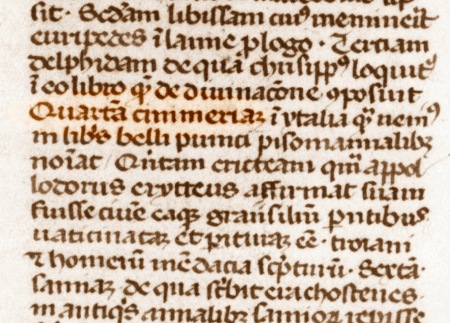

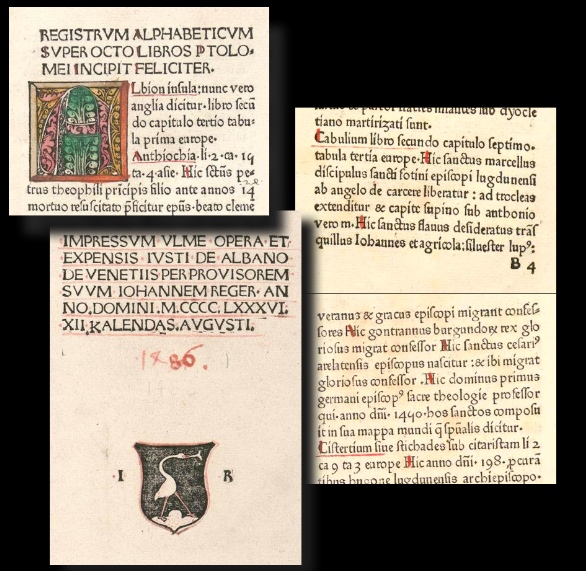

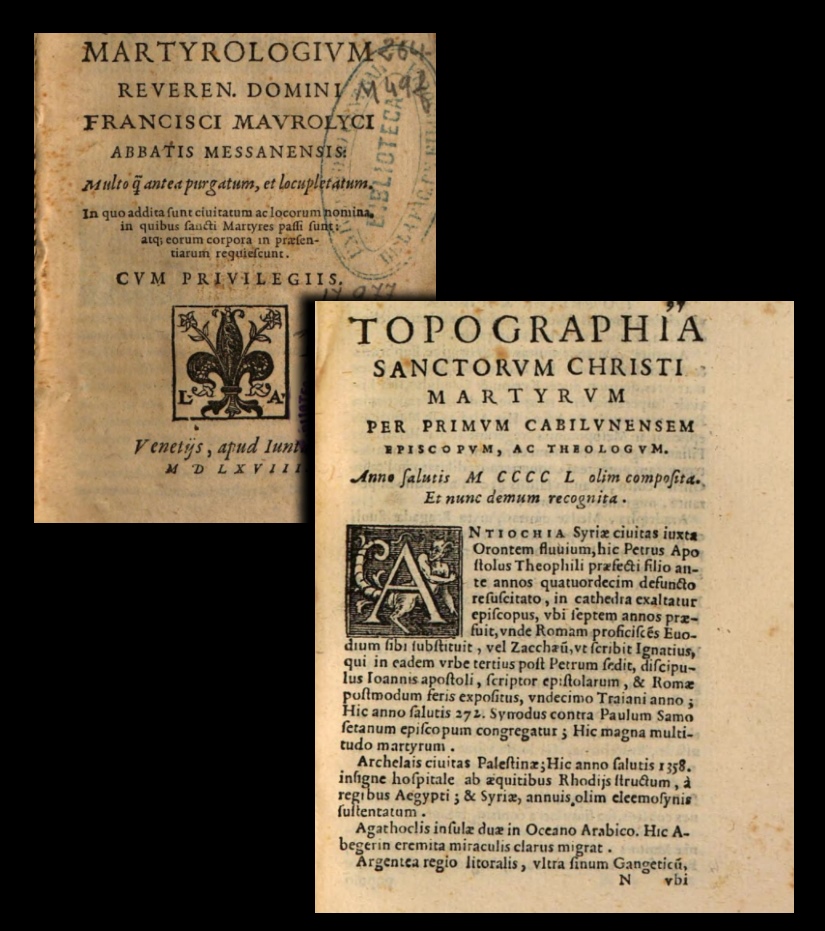

When we began our investigation into the myth of the Cimmerian and Cumaean Sibyl, we started by considering a number of excerpts written by Francesco Maurolico in 1568.

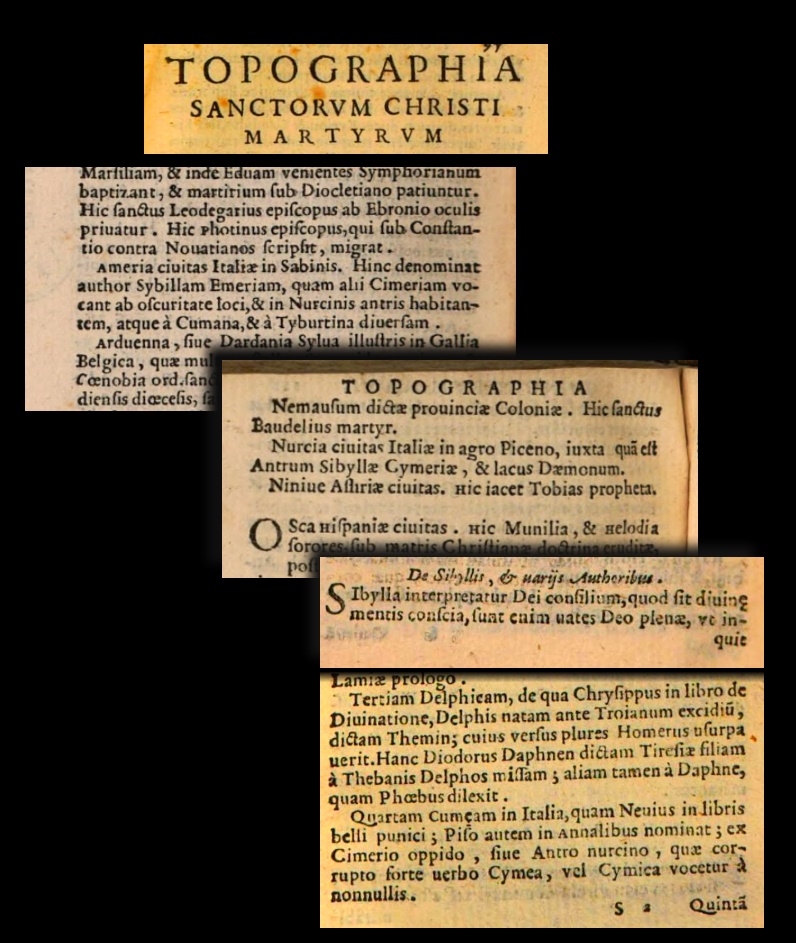

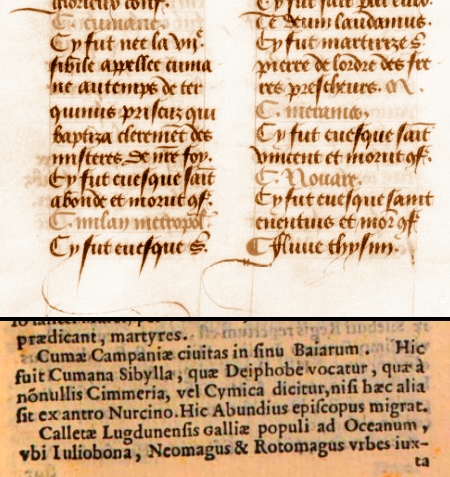

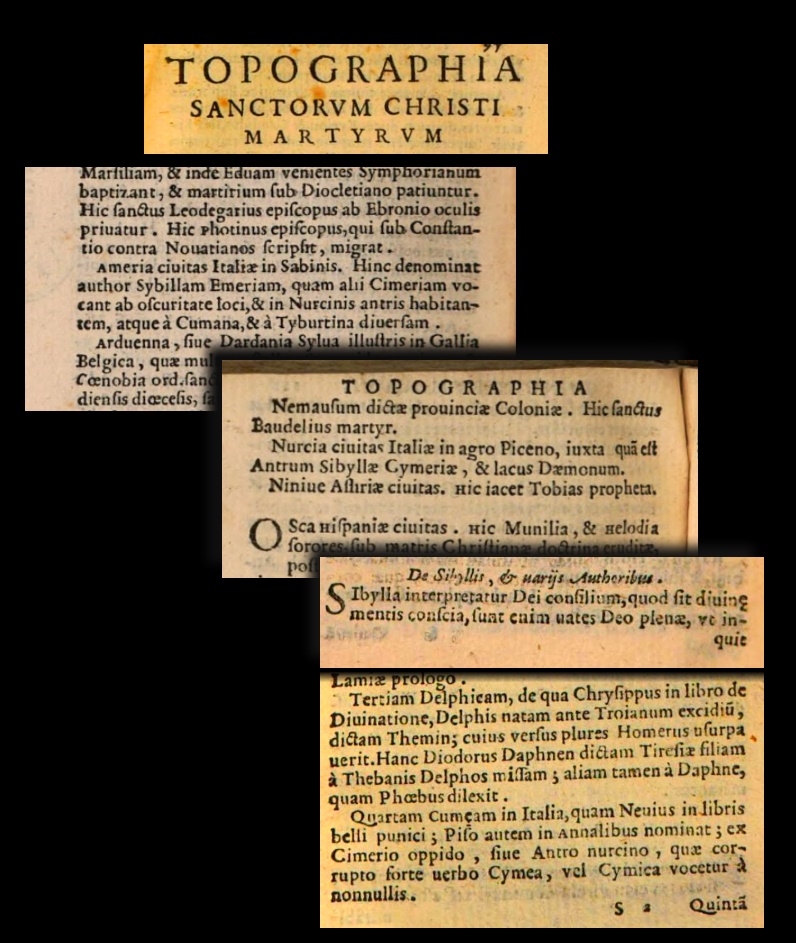

In his “Topographia Sanctorum Christi Martyrum”, Maurolico states the following:

«The fourth Sibyl is the Cumaeam, whom Naevius mentions in his books about the Punic war, and Piso in his annals as well; from the Cimeriam castle, also known as the Cave of Norcia, which some call by the corrupted name of 'Cymea' or 'Cymica' [...] Cumae, a town of Campania lying by the gulf of Baiae. Here was the Cumaean Sibyl, who was also called Deiphobe, and by some named as Cimmeria or Cymica, but in truth the latter is a different one in the cavern of Norcia [....] Ameria, an Italian town set in the Sabine region. From this town the author names the 'Emerian Sibyl', who others call the 'Cimeriam' owing to the uncertainty of the place; she lives in the caverns of Norcia, and is different from both the Cumaean and the Tiburtine Sibyls».

When we started our exploration, we sensed that some kind of confusion affected Maurolico's words, with all his manifest efforts to corroborate the idea that the Apennine Sibyl, whose legend pertains to a cavern located in the mountains raising in the vicinity of Norcia, in central Italy, should be identified with the fourth Sibyl in Lactantius' list, the Cimmerian.

Is Maurolico right?

The right answer is no. And possibly, from a certain point of view, yes.

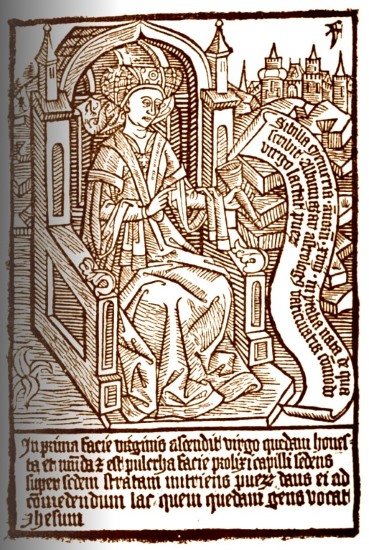

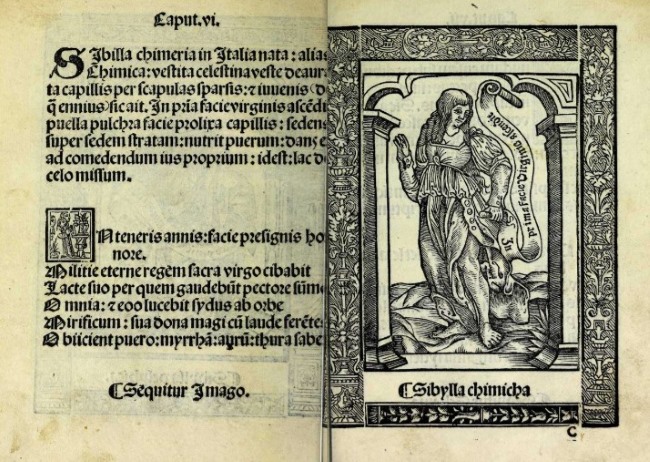

Maurolico is right when he says that the Cimmerian or Cumeam or Chemical Sibyl, the fourth Sibyl (see Fig .1), belongs to Cumae, as we ourselves have fully shown by our investigation. However, he is inconsistent when he says that the Cumaean is truly the Cimmerian, while in another passage he writes that the Cimmerian «is different from [...] the Cumaean»:

In addition to that, he is wrong when he expresses all his confidence in the unfounded assumption that the Sibyl of Norcia is Lactantius' Cimmerian Sibyl, the fourth sibilline oracle in the list, basing his surmise on the name of a village allegedly set by the Cave of Norcia, whose name is - according to Maurolico - 'Cimerian' or “Ameria'.

However, Maurolico's assumption is totally wrong. Because we have fully demonstrated that, in the antique tradition, the town of the Cimmerians was consistently situated by all ancient writers in Cumae, in the Italian province of Campania. Thus, Cimmerians had nothing to do with the Apennines, and equally they had nothing to do with Norcia. And the fourth Sibyl, the Cimmerian oracle, is not a Sibyl from Norcia, but a Sibyl from Cumae, as positively stated by all available classical authors.

Why did Maurolico incur this error?

His misleading statements appear to be the more perplexing when we consider that the identification of Cumae as the original place in which the fourth Cimmerian Sibyl vaticinated was not an unknown feature in Maurolico's times. Scholars of both his and later ages read the classical authors as we do today, and they found out the same pieces of information as we were able to retrieve in our present days: the Cimmerians lived by Cumae, and they had their prophesying Sibyl, who was called 'Cimmerian' after their own name.

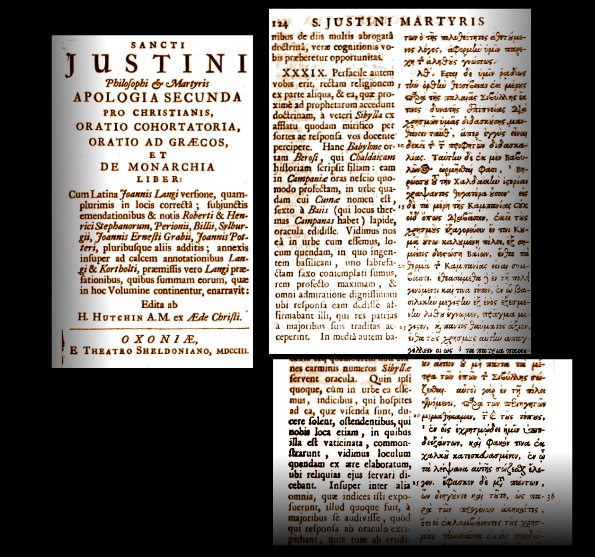

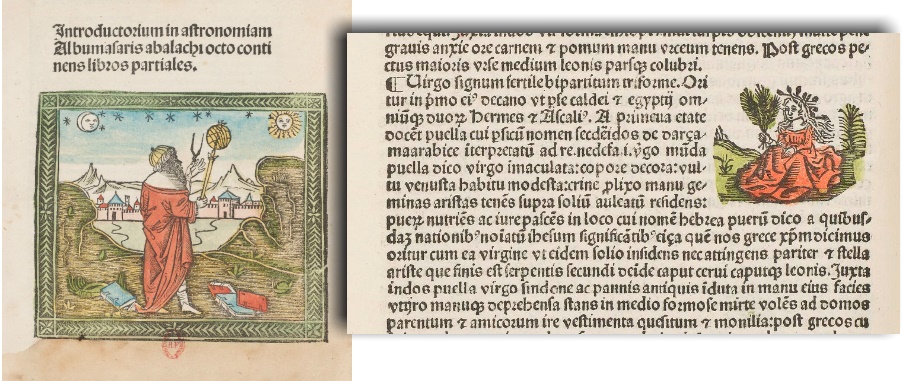

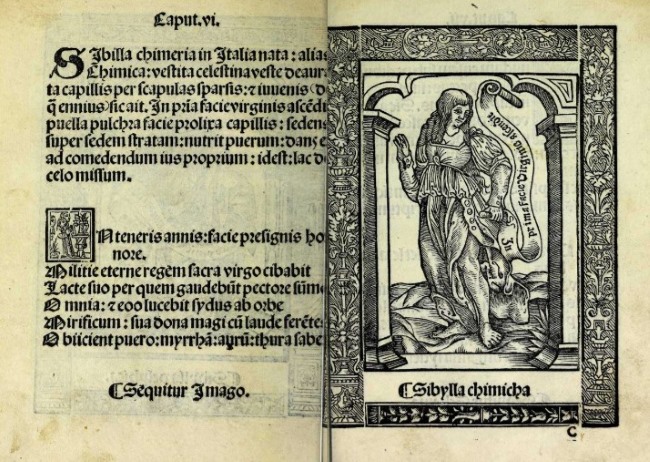

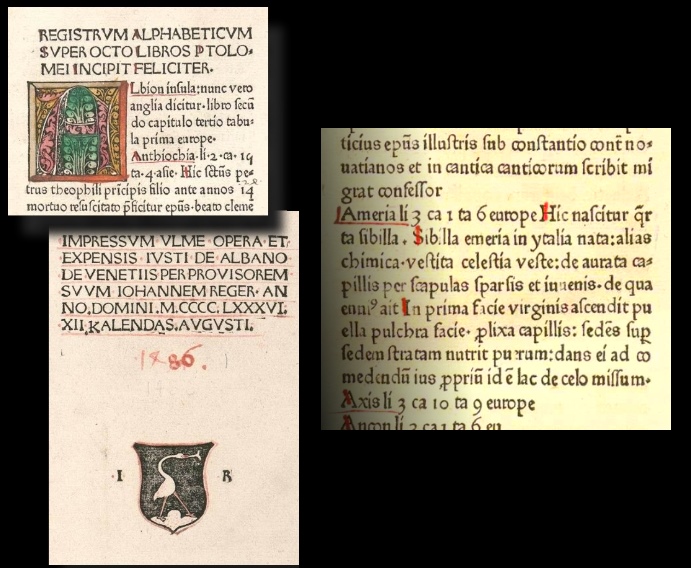

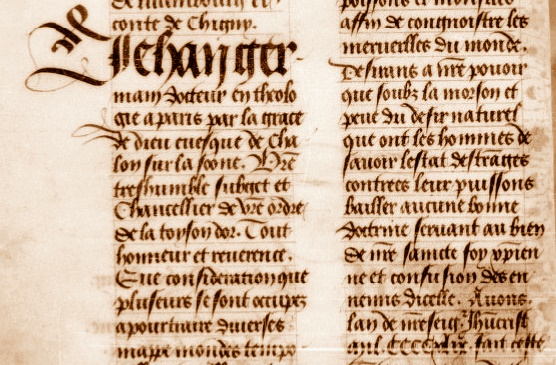

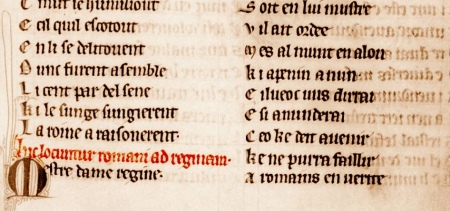

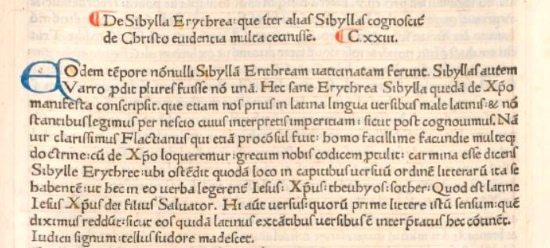

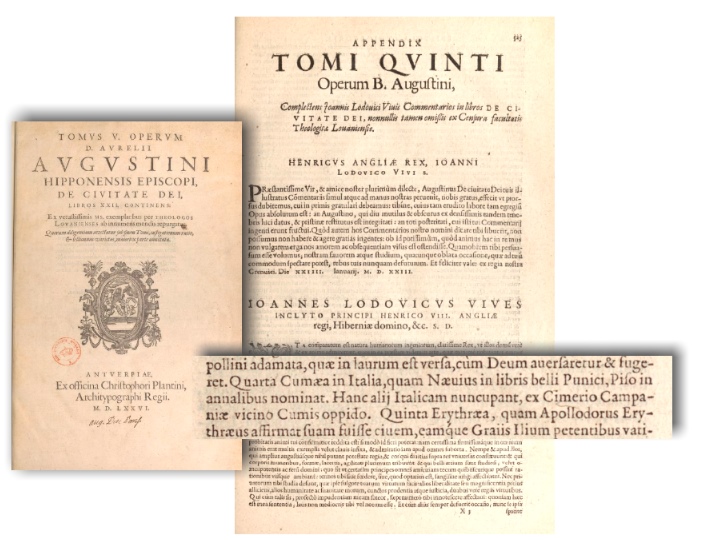

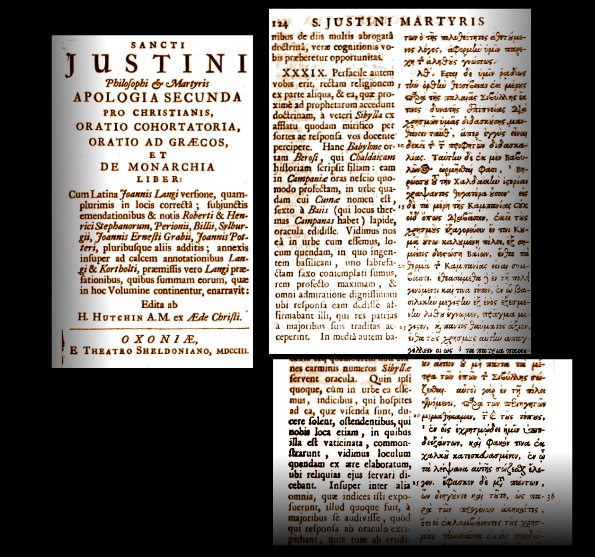

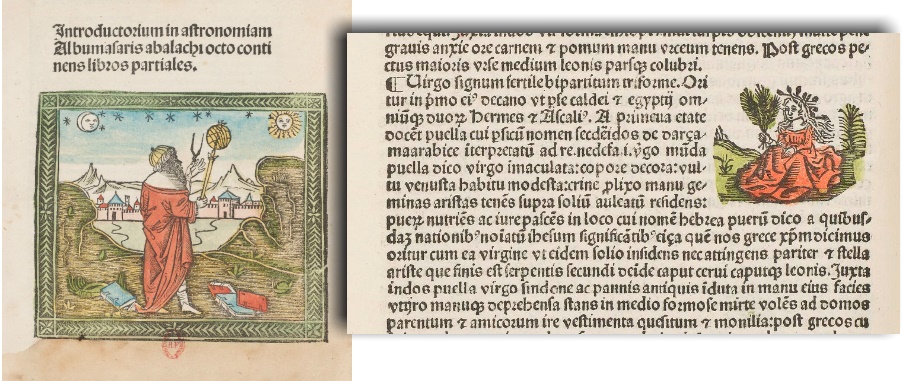

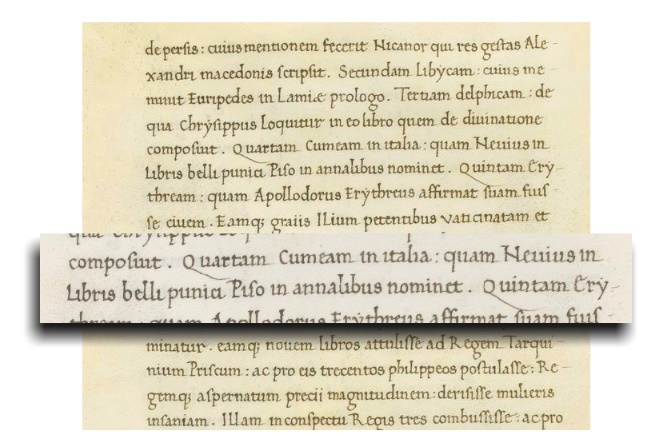

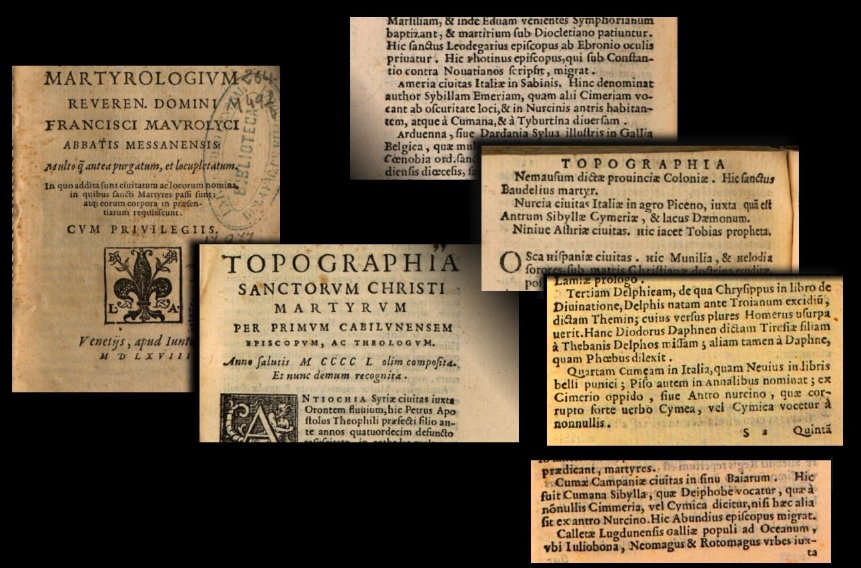

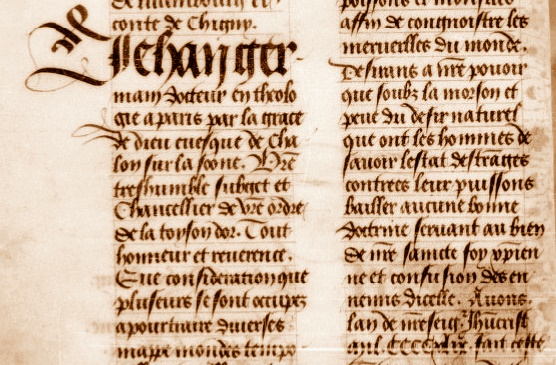

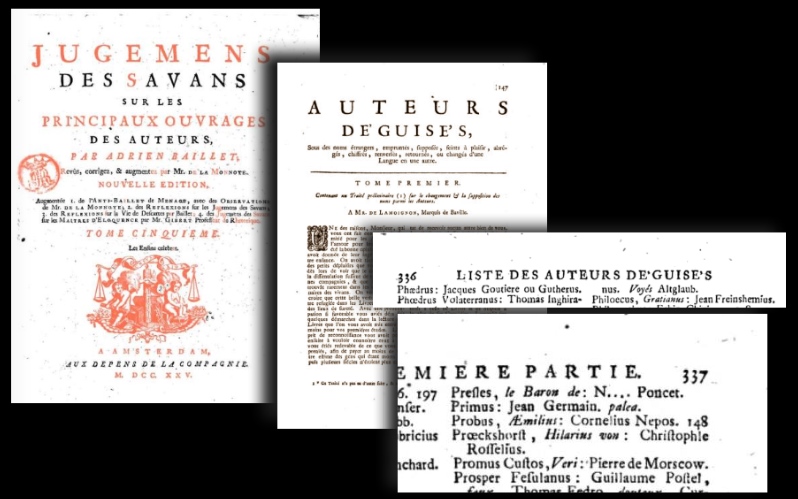

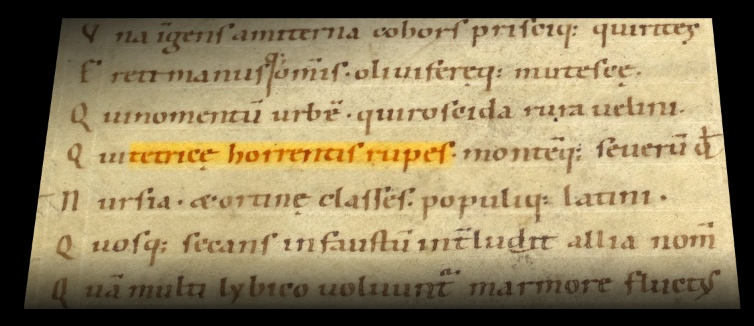

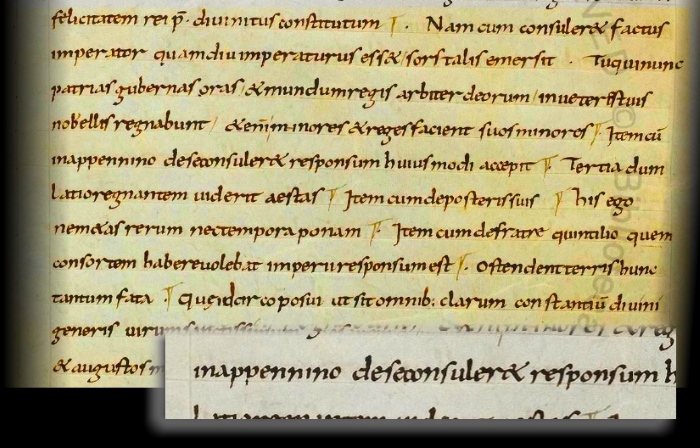

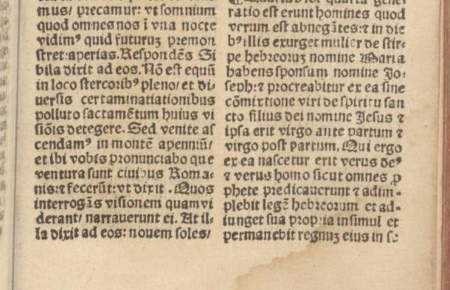

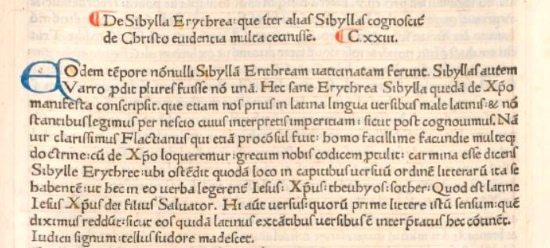

Let's take, for instance, a commentary written in 1523 by Juan Luis Vives, a great sixteenth-century Spanish scholar, a book published in Antwerp in 1576 (Fig. 2). In commenting a famous excerpt drawn from Augustine of Hippo's “The City of God” (Book XVIII, Chapter XXIII), in which Augustine enlists the Sibyls as pagan heralds of the Salvation, Juan Luis Vives reports the famous list of ten Sibyls originally contained in Lactantius' “Divinae Institutiones”.

But, when he gets to the fourth Sibyl, he quotes the words by Lactantius with the addition of a highly remarkable sentence:

«The fourth [Sibyl is] Cumaean in Italy, whom Naevius mentions in his book on the Punic war, and Piso in his annals. Some call her Italian, from the Cimmerian town which is not far from Cumae in the Campania province».

[In the original Latin text: «Quarta [Sibylla est] Cumaea in Italia, quam Naevius in libris belli Punici, Piso in annalibus nominat. Hanc alij Italicam nuncupant, ex Cimerio Campaniae vicino Cumis oppido»].

Juan Luis Vives could not have been clearer than that: the fourth Sibyl is an Italian oracle from a small town near Cumae. And the town's name - as we know from antique authors - is Cimmerian.

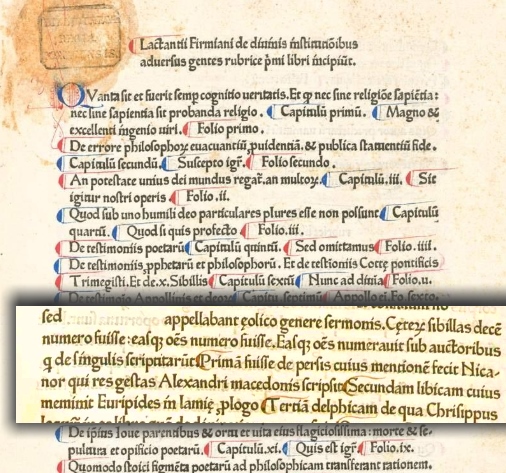

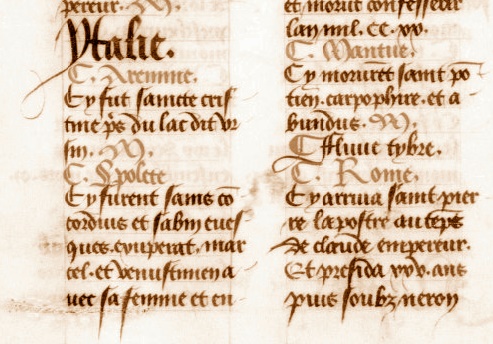

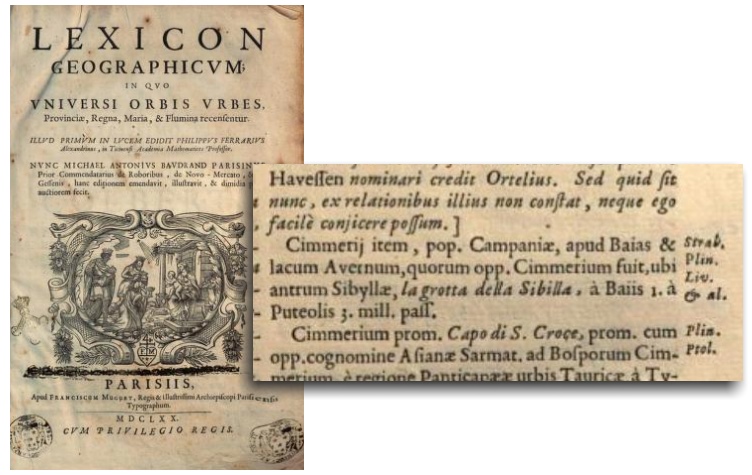

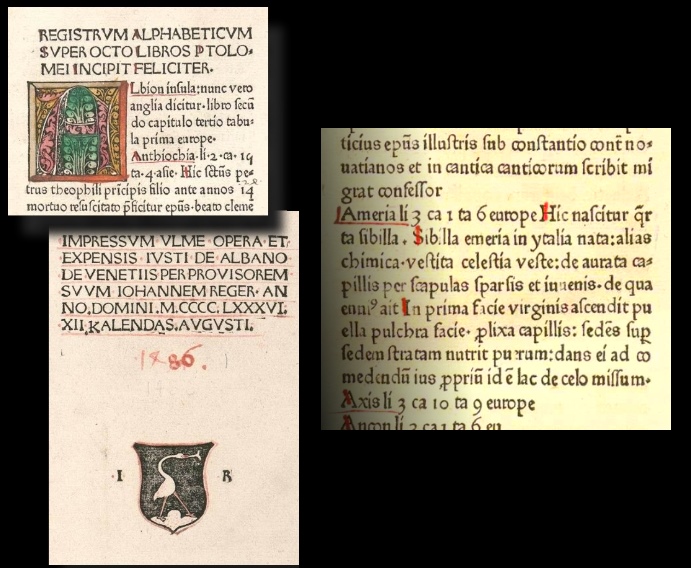

And let's consider another work released a century later, the “Lexicon Geographicum” (“Geographical Dictionary”) published by a French scholar, Michel Antoine Baudrand, in 1652 (Fig. 3). Under letter 'C', we find another clear reference to the town of the Cimmerians:

«Cimmerians, population of Campania, in the vicinity of Baiae and the lake of Avernus, whose town was called Cimmerian, where the Sibyl's cave is, 'la grotta della Sibilla' [in Italian], 1 mile from Baiae and 3 miles from Pozzuoli».

[In the original Latin text: «Cimmerij item, pop. Campaniae, apud Baias et lacum Avernum, quorum opp. Cimmerium fuit, ubi antrum Sibyllae, 'la grotta della Sibilla', a Baiis 1 a Puteolis 3 milia passuum»].

Again, in the seventeenth century too the Cimmerians were placed in the vicinity of Lake Avernus, very far from central Apennines, where Norcia lies.

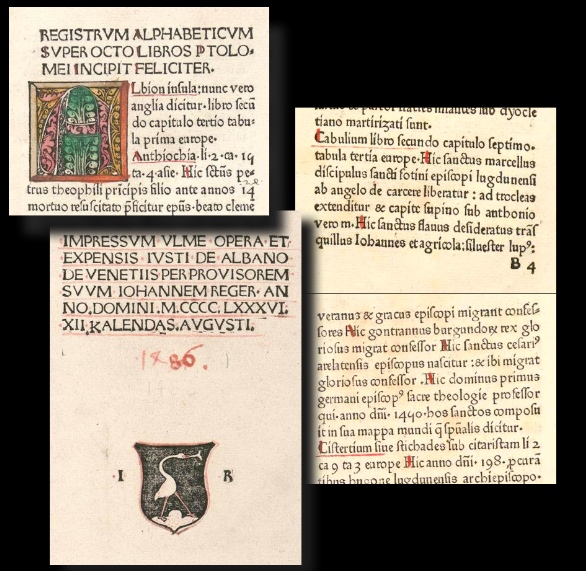

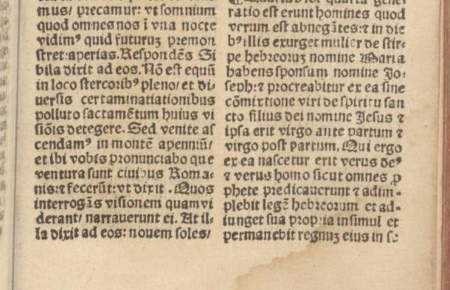

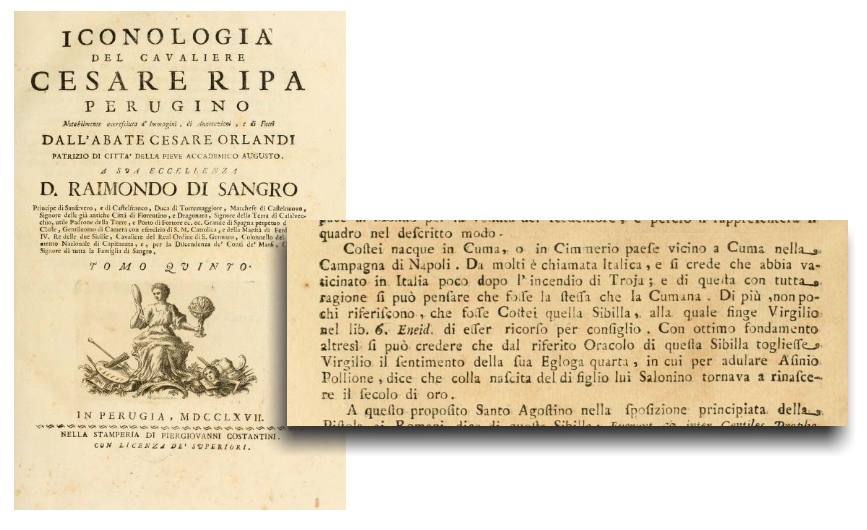

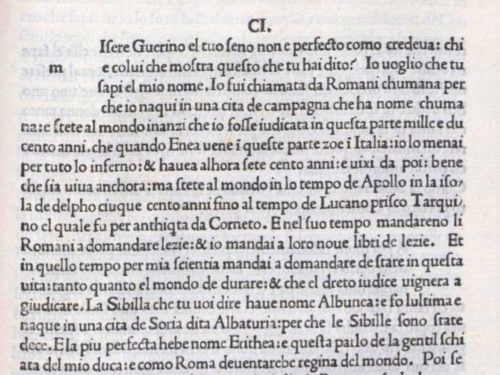

And here is another interesting example coming to us from a century later. In 1767, an Italian nobleman and scholar, Cesare Orlandi, who was born in an Umbrian town and whose family originated from the province of Marche, published an updated edition of a famous work, the “Iconologia”, originally edited by Cesare Ripa in 1593 (Fig. 4). In his own revised edition, Cesare Orlandi included a whole section on Sibyls, and the following is what he wrote on the Cimmerian:

«Cumean Sibyl, or Cimmerian: [...] she was born in Cumae, or in a Cimmerian village in the surroundings of Cumae, in the countryside of Naples. Many call her Italic, and it is reputed that she was vaticinating in Italy after the great fire of Troy; and of her, with full reason, we can reckon that she is the same as the Cumaean. Actually many authors report that this Sibyl was the Cumaean, to whom Vergilius pretends his characters turned for advice in Book 6 of his "Aeneid"».

[In the original Italian text: «Sibilla Cumea, ovvero Cimmeria: [...] Sibilla Cumea, ovvero Cimmeria: [...] Costei nacque in Cuma, o in Cimmerio paese vicino a Cuma nella Campagna di Napoli. Da molti è chiamata Italica, e si crede che abbia vaticinato in Italia poco dopo l'incendio di Troia; e di questa con tutta ragione si può pensare che fosse la stessa che la Cumana. Di più, non pochi riferiscono, che fosse Costei quella Sibilla, alla quale finge Virgilio nel lib. 6 'Eneid.' di esser ricorso per consiglio»].

Does Cesare Orlandi write that the Cimmerian Sibyl has any connection with a Sibyl in Norcia? Not at all. And this fact is of remarkable significance: because Cesare Orlandi was born in Città della Pieve, an Umbrian town, and his family came from Fermo, in the Marche region; if any relation had really existed between the Cimmerian and a Sibyl from Norcia - a town sitting between Umbria and Marche - Orlandi would certainly know, and would certainly tell. But he does not.

Thus, no doubt can still remain as to whether late-Renaissance scholars and later men of letters were fully informed about the true origin of the Cimmerian Sibyl: they knew that she had vaticinated in the area of Cumae, and no relation to the Apennines could be established in any way.

Definitely, Maurolico proves to be on the wrong side. But why was he so confident in his belief that the Apennine Sibyl was Lactantius' fourth Sibyl?

Though we have no conclusive information on that specific aspect, we will try to end our search with a few final consideration, which we will state in the next (and last) article.

Una Sibilla chiamata Cimmeria: un'investigazione sulla possibile relazione con la Sibilla Appenninica - 11. Lunga è la strada dalla Sibilla Cimmeria agli Appennini

Quando abbiamo cominciato la nostra investigazione attraverso il mito delle Sibille Cimmeria e Cumana, abbiamo preso le mosse da una serie di brani scritti da Francesco Maurolico nel 1568.

Nella sua “Topographia Sanctorum Christi Martyrum”, Maurolico si esprimeva nel seguente modo:

«La quarta Sibilla è la Cumea, di cui parla Nevio nei suoi libri dedicati alla Guerra Punica, a anche Pisone nei propri annali; dal castello Cimerio, conosciuto anche con il nome di Antro nursino, che alcuni chiamano con il nome corrotto di 'Cymea' o 'Cymica' [...] Cuma, città della Campania nel golfo di Baia. Qui fu la Sibilla Cumana, chiamata anche Deifobe, che alcuni indicano come Cimmeria o Cymica, se questa non fosse un diverso oracolo posto nella caverna di Norcia [...] Ameria, città dell'Italia posta nella regione Sabina. Da questa città l'autore denomina la 'Sibilla Emeria', che altri chiamano 'Cimeria' a causa dell'incertezza sul luogo; essa vive nell'antro di Norcia, ed è diversa sia dalla Cumana che dalla Tiburtina [...]».

Quando la nostra ricerca ha avuto inizio, non abbiamo potuto evitare di pensare che le parole di Maurolico fossero affette da un qualche genere di confusione, essendo evidente il suo palese tentativo di avallare l'idea che la Sibilla Appenninica, la cui leggenda riguarda una grotta collocata tra le montagne che si innalzano in prossimità di Norcia, nell'Italia centrale, dovesse essere identificata con la quarta Sibilla elencata nella lista di Lattanzio, la Cimmeria.

Ma Maurolico era veramente nel giusto?

La risposta corretta è no. E, forse, da un certo punto di vista, anche sì.

Maurolico, infatti, ha ragione quando afferma che la Sibilla Cimmeria o Cumea o Chimica, la quarta Sibilla (Fig. 1), appartiene a Cuma, come noi stessi abbiamo potuto dimostrare per mezzo della nostra investigazione. Invece, egli risulta essere in tutta evidenza inconsistente quando dichiara che la Cimmeria «è diversa [...] dalla Cumana».

Inoltre, egli prende un abbaglio quando manifesta di voler riporre ogni sua certezza nell'infondata ipotesi che la Sibilla di Norcia possa essere la Sibilla Cimmeria di Lattanzio, il quarto oracolo sibillino contenuto nell'enumerazione classica, basando la propria convinzione sul nome di un villaggio che esisterebbe nelle vicinanze della Grotta di Norcia, e il cui nome sarebbe - secondo Maurolico - 'Cimerio' o 'Amerio'.

Questa affermazione di Maurolico è totalmente errata. Abbiamo infatti pienamente dimostrato come, nella tradizione antica, la città dei Cimmèri fosse unanimemente collocata, da tutti gli autori classici, presso Cuma, nella provincia italica della Campania. Dunque, i Cimmèri non avevano nulla a che fare con gli Appennini, e parimenti nulla avevano a che fare con Norcia. E la quarta Sibilla, la Cimmeria, non è affatto una Sibilla di Norcia, ma una Sibilla di Cuma, come positivamente e indubitabilmente affermato da tutti i riferimenti testuali classici oggi disponibili.

Ma perché Maurolico cadde in questo errore?

Le sue fuorvianti affermazioni appaiono suscitare ancor maggiore perplessità quando si consideri che l'identificazione di Cuma come luogo originale presso il quale la quarta Sibilla, Cimmeria, vaticinava non costituiva affatto informazione ignota ai contemporanei di Maurolico. Gli studiosi del suo tempo e dei secoli successivi, infatti, erano in grado di leggere i testi degli antichi autori esattamente come noi facciamo oggi, e potevano reperire gli stessi elementi informativi che anche noi abbiamo potuto ritrovare ai nostri giorni: i Cimmèri vivevano a Cuma, e disponevano di una propria Sibilla oracolare, che era chiamata 'Cimmeria', traendo il proprio nome dall'appellativo stesso di quel popolo.

Prendiamo, ad esempio, un'opera scritta nel 1523 da Juan Luis Vives, un noto erudito spagnolo del sedicesimo secolo, un libro pubblicato in Anversa nel 1576 (Fig. 2). Nel commentare un famoso brano tratto da "La Città di Dio" di Agostino di Ippona (Libro XVIII, Capitolo XXIII), nel quale Agostino arruola le Sibille tra gli araldi pagani della Salvezza, Juan Luis Vives cita la famosa lista di dieci Sibille originariamente contenuta nelle "Divinae Institutiones" di Lattanzio.

Ma, quando egli arriva alla quarta Sibilla, Vives riferisce le parole di Lattanzio aggiungendo ad esse una frase ben significativa:

«La quarta [Sibilla è] la Cumea in Italia, di cui parla Nevio nei libri dedicati alla Guerra Punica, e anche Pisone nei propri annali. Alcuni la chiamano Italica, dalla città dei Cimmèri posta in prossimità di Cuma in Campania».

[Nel testo originale latino: «Quarta [Sibylla est] Cumaea in Italia, quam Naevius in libris belli Punici, Piso in annalibus nominat. Hanc alij Italicam nuncupant, ex Cimerio Campaniae vicino Cumis oppido»].

Juan Luis Vives non avrebbe potuto essere più chiaro: la quarta Sibilla è un oracolo italiano attivo in una piccola città posta presso Cuma. E l'appellativo della città - come già sappiamo dalle fonti antiche - è Cimmeria.

E proviamo a considerare un'altra opera diffusa nel secolo successivo, il “Lexicon Geographicum”, pubblicato da uno studioso francese, Michel Antoine Baudrand, nel 1652 (Fig. 3). Sotto la lettera 'C', troviamo un ulteriore, chiarissimo riferimento alla città dei Cimmèri:

«Cimmèri, popolazione della Campania, nell'area di Baia e del Lago d'Averno, la cui città fu chiamata Cimmeria, presso cui si trova l'antro della Sibilla, 'la grotta della Sibilla', 1 miglio da Baia e 3 miglia da Pozzuoli».

[Nel testo originale latino: «Cimmerij item, pop. Campaniae, apud Baias et lacum Avernum, quorum opp. Cimmerium fuit, ubi antrum Sibyllae, 'la grotta della Sibilla', a Baiis 1 a Puteolis 3 milia passuum»].

Ed ecco che, di nuovo, anche nel diciassettesimo secolo i Cimmèri venivano posizionati presso il Lago d'Averno, quindi molto lontano dall'Appennino umbro-marchigiano, dove si trova Norcia.

Ed ecco un ulteriore interessantissimo esempio, a noi proveniente dal secolo ancora successivo. Nel 1767, un aristocratico ed erudito italiano, Cesare Orlandi, nato in una città dell'Umbria e la cui famiglia era originaria delle Marche, pubblicò una edizione aggiornata di un'opera molto rinomata, il cui titolo era "Iconologia", originariamente data alle stampe da Cesare Ripa nel 1593 (Fig. 4). Nella propria edizione riveduta e ampliata, Cesare Orlandi inserì anche un'intera sezione dedicata alle Sibille, ed ecco ciò che egli scrisse a proposito della Cimmeria:

«Sibilla Cumea, ovvero Cimmeria: [...] Costei nacque in Cuma, o in Cimmerio paese vicino a Cuma nella Campagna di Napoli. Da molti è chiamata Italica, e si crede che abbia vaticinato in Italia poco dopo l'incendio di Troia; e di questa con tutta ragione si può pensare che fosse la stessa che la Cumana. Di più, non pochi riferiscono, che fosse Costei quella Sibilla, alla quale finge Virgilio nel lib. 6 'Eneid.' di esser ricorso per consiglio».

Cesare Orlandi ha forse scritto che la Sibilla Cimmeria presenta una qualsivoglia connessione con una Sibilla degli Appennini? Niente affatto. E, in effetti, questo elemento appare essere estremamente significativo: perché Cesare Orlandi era nato a Città della Pieve, città dell'Umbria, e la sua famiglia proveniva da Fermo, nelle Marche: se una qualsiasi relazione fosse realmente esistita tra la Cimmeria e una Sibilla di Norcia - città posta esattamente tra l'Umbria e le Marche - Orlandi lo avrebbe certamente saputo, e lo avrebbe sicuramente riferito e scritto. Ma egli non lo fa.

Dunque, nessun dubbio può ancora sussistere in merito al fatto che gli eruditi e gli studiosi del tardo Rinascimento, nonché i letterati dei secoli successivi, avessero piena cognizione della reale origine della Sibilla Cimmeria: essi sapevano che quell'oracolo aveva reso i propri vaticini nell'area di Cuma, e che non esisteva alcun motivo o ragione per collegare in alcun modo quella Sibilla con la catena degli Appennini.

È quindi un dato di fatto che Maurolico risulta trovarsi dal lato del torto. Ma come è possibile che egli si dichiari così sicuro della propria convinzione a proposito dell'identificazione tra Sibilla Appenninica e quarta Sibilla di Lattanzio?

Benché non disponiamo attualmente di alcuna informazione decisiva in merito a questa specifica questione, tenteremo comunque di concludere la nostra ricerca con alcune considerazioni finali, che andremo a esplicitare nel prossimo (e ultimo) articolo.

12 Jul 2018

A Sibyl called Cimmerian: exploring the potential link to the Apennine Sibyl - 10. The Cimmerian Sibyl as an earlier Cumaean

When the Roman Empire was flourishing, the Cimmerians too had already become a legendary population long vanished from the sight of history, just like the Cumaean Sibyl who had disappeared centuries earlier. For the Romans themselves, Cimmerians were but a faint recollection: a legendary population whose subterranean abode once concealed by the Lake Avernus was extant nomore already in the early Roman age. Not the least remnant of their subterranean dwellings and tunnels is to be found in our present days, and the more so if we consider the destructive earthquakes that have repeatedly been striking the area of Lake Avernus and the Phlegraean Fields across the centuries (for instance, let's consider the 1538 earthquake when a small volcano, Monte Nuovo, was generated in a handful of days).

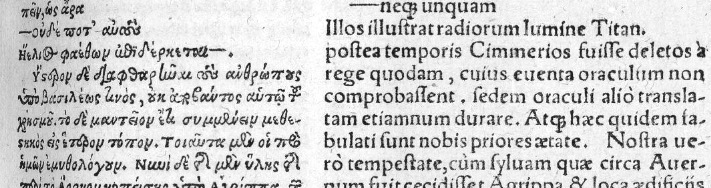

Despite all that, Strabo, who writes in the first century, reports an additional, remarkable detail (Fig. 2):

«Later on the Cimmerians were destroyed by a certain king, because the response of the oracle did not turn out in his favour; the seat of the oracle, however, still endures, although it has been removed to another place».

[In the Latin translation from the original Greek text: «postea temporis Cimmerios fuisse deletos a rege quodam, cuius eventa oraculum non comprobassent, sedem oraculi alio translatam etiamnun durare»].

According to Strabo, at his age Cimmerians had already been wiped out centuries earlier. In another passage we already quoted, it's Strabo himself who adds that «Ephorus maintained that this site was of the Cimmerians, about whom he says that they dwell in underground premises» [«Ephorus vero Cimmeriis locum illum dicans, hos abitare ait in subterraneis aedificiis» in Latin]. And Ephorus was a local historian, who lived in Cumae during the fourth century B.C. (his books no longer exist).

This means that Cimmerians vanished from Lake Avernus centuries and centuries before the arrival of the Romans in Cumae, but «the seat of the oracle, however, still endures, although it has been removed to another place».

Could it be that the Cimmerian Sibyl, who provided her responses in an underground site in Cumae by querying the dead through necromantic practices, had subsequently moved to another shrine, again situated in the town of Cumae, following the destruction of her original site, and that the Sibyl at the new site had taken the name of 'Cumaean'?

Could it be that the original, antique Cimmerian Sibyl had taken on the final name of 'Cumaean Sibyl', after having abandoned her former subterranean site, following its obliteration?

According to many scholars, the answer is positive. Jacques Hergon, a renowned French latinist, and other researchers (Luca Antonelli) consider the Cimmerian Sibyl as an early prophetess providing responses in the area of Cumae, by querying the dead through necromancy. Later on, after the destruction of her original underground shrine, the oracle moved to another temple in downtown Cumae, assuming the name of 'Cumaean Sibyl', providing her prophecies by writing them on a multiplicity of oak leaves, and then letting the leaves whirl freely in the whiffs of the wind («volent rapidis ludibria ventis», as Vergilius says), so as to render the oracular response almost incomprehensible.

So, the Cimmerian Sibyl and the Cumaean Sibyl would actually be the same prophetess, the former being only an earlier name for the latter.

This identity would provide a full explanation for the suspicious confusion in the names attributed to the fourth Sibyl which arises in different versions of the list stated by Lactantius: 'Cimmeriam' in some of them, and 'Cumeam' in other manuscripts. In the suggested theory, the fourth Sibyl would be just identical to the seventh, the Cumaeam, but called by her original, more ancient name.

And another peculiar literary intricacy, connected to the description of the Cumaean Sibyl provided by Vergilius in his “Aeneid”, would find its correct solution.

In Book VI, Vergilius says that, after arriving in Cumae, «Aeneas the pious ascends the citadel which is ruled by glorious Apollo and heads to the ghastly, secret recesses, the huge cavern of the Sibyl» («pius Aeneas arces, quibus altus Apollo presidet horrendaque procul secreta Sibyllae antrum immane petit» in Latin). He is visiting what is to be identified with the Cumaean Sibyl, who provides her responses acting as the voice of Greek deity Apollo:

«Such reins Apollo shakes in the body of the frenzied prophetess, and such spurs he urges in her heart».

[In the original Latin text: «ea frena furenti concutit et stimolos sub pectore vertit Apollo»].

But then, later in the same Book, the Sibyl commands Aeneas to make an offering to Hecate, the Greek goddess associated to witchcraft and necromancy, and the rite is carried out at a cave by the Lake Avernus. Now, the Sibyl has taken on the full attributes of the older Cimmerian prophetess:

«A deep cave was there, with a huge, frighful opening, hard to reach, protected by the gloomy lake and the darkness of the woods [... Aeneas] put the offerings on the sacred fire, a prominent donation, appealing to Hecate by his voice, calling to the heaven and to vast Erebus».

[In the original Latin text: «Spelunca alta fuit vastoque inmanis hiatu, scrupea, tuta lacu nigro nemoremque tenebris [...] ignibus imponit sacris, libamina prima, voce vocans Hecaten caeloque Ereboque potentem»].

In the above excerpts, Vergilius would be just portraying the two aspects of the Cimmerian / Cumaean Sibyl: the necromantic prophetess (Cimmerian) and the oracle of Apollo (Cumaean). Two different aspects for the same Sibyl: the Sibyl of Cumae.

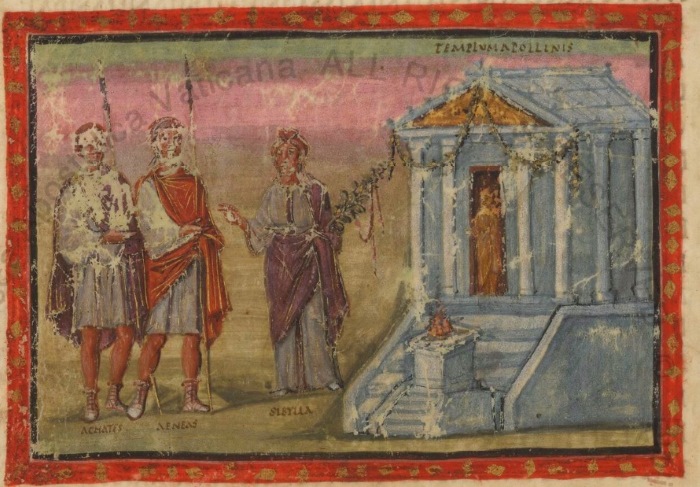

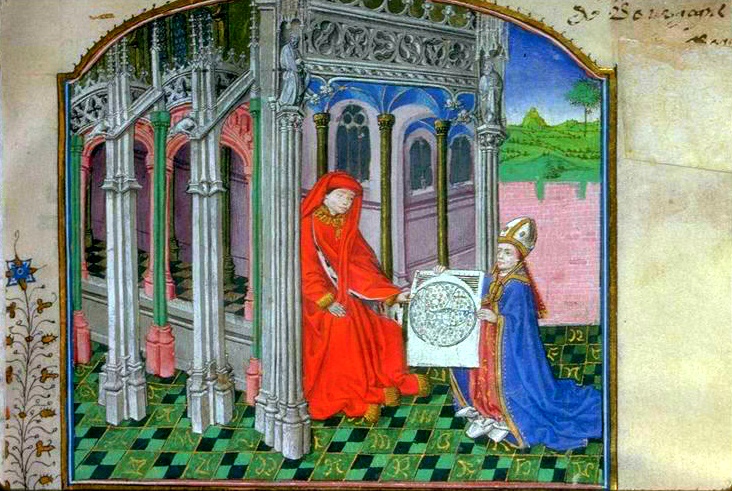

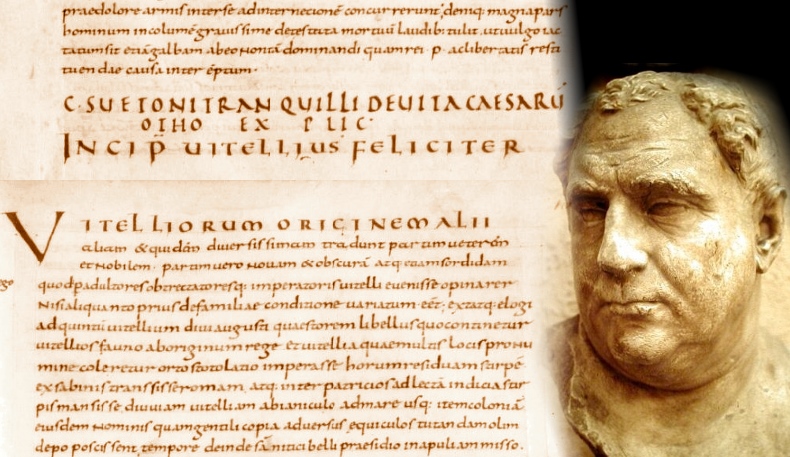

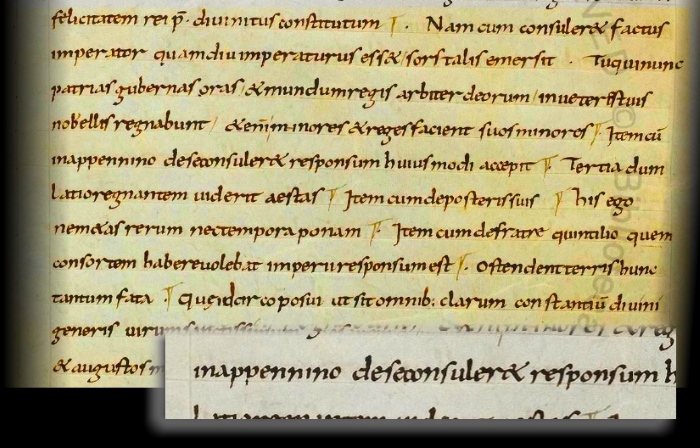

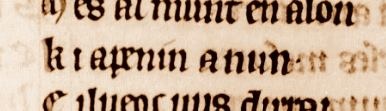

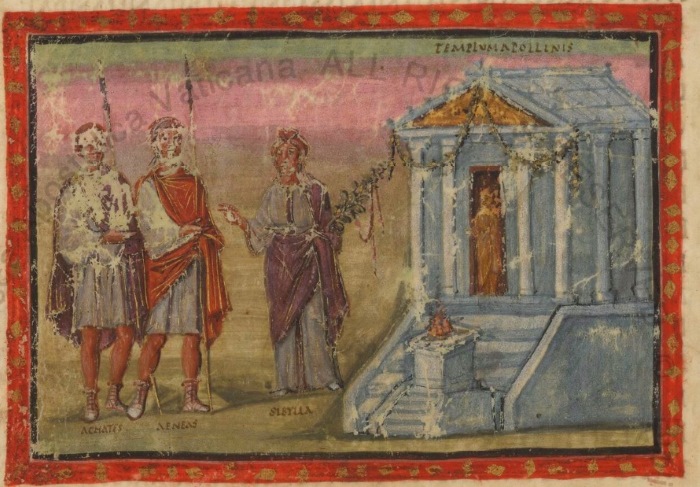

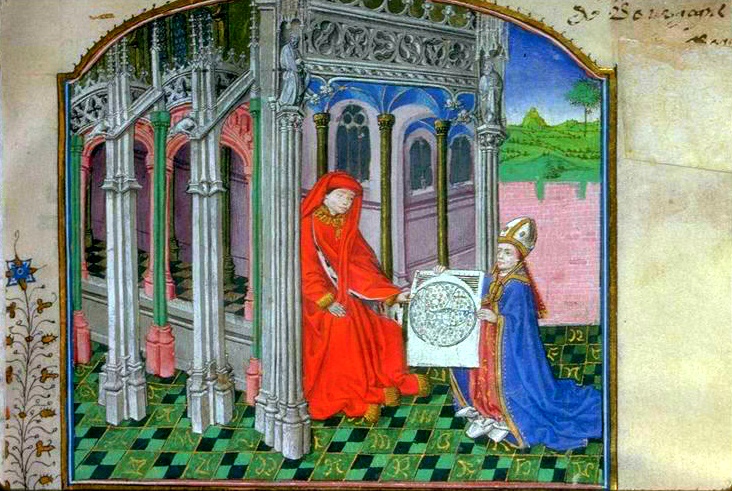

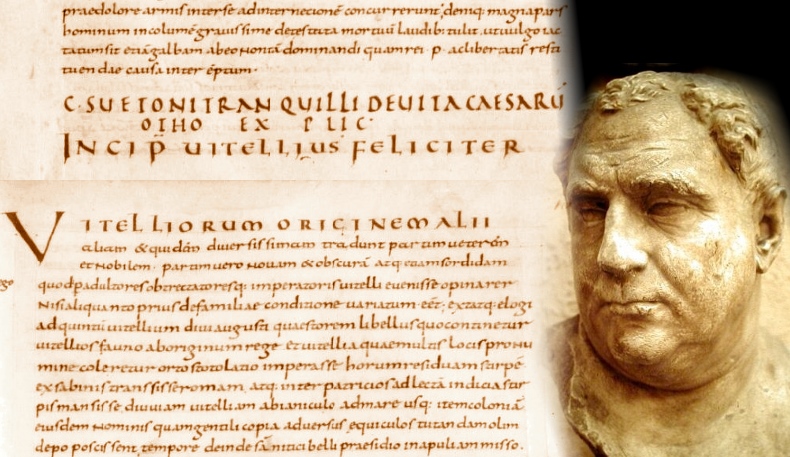

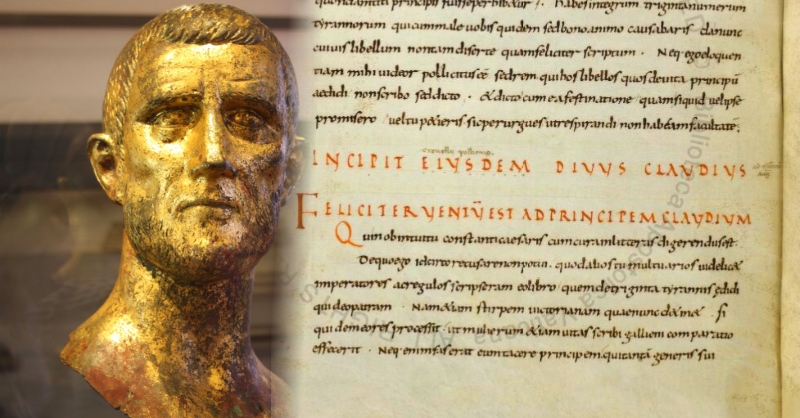

A Sibyl who re-emerges from the mists of a lost, almost forgotten past, as portrayed in a most precious illuminated manuscript (Vat. Lat. 3225) preserved at the Vatican Apostolic Library in Rome: one of the most ancient manuscripted relics coming to us from the classical Roman world, dating back to the fourth century and featuring a stunning picture of Aeneas and his comrade Achates as they stand before the Cumaean Sibyl and her shrine dedicated to Apollo (Fig. 1).

We are getting closer and closer to the end of our amazing journey into myth and sibilline lore. Time has come now to provide an answer to the initial question we had posed at the very beginning of our travel: is the Apennine Sibyl, the Sibyl of Norcia, connected in any way to the Cimmerian Sibyl, as alleged by a sixteenth-century abbot from Sicily, Francesco Maurolico, in his “Topographia Sanctorum Christi Martyrum”?

The answer seems now to be clear. And we will detail it in the next article.

Una Sibilla chiamata Cimmeria: un'investigazione sulla possibile relazione con la Sibilla Appenninica - 10. La Sibilla Cimmeria, antecedente della Cumana

Quando l'Impero Romano giungeva all'apice della propria potenza, anche i Cimmèri erano già divenuti un popolo leggendario, svanito da tempo dal teatro della storia, proprio come accaduto anche alla Sibilla Cumana, scomparsa già da molti secoli. Per gli stessi Romani, i Cimmèri non costituivano altro che un flebile ricordo: una popolazione leggendaria, le cui dimore sotterranee, un tempo celate in prossimità del Lago d'Averno, non esistevano già più sin dall'epoca in cui Roma era ancora giovane. Ai nostri giorni, nemmeno le più insignificanti vestigia di quelle residenze occultate nella terra, né di quei tunnel, possono essere più rintracciate in alcun modo, e questa impossibilità risulta essere tanto più evidente quando si considerino i terremoti e gli eventi catastrofici che hanno ripetutamente colpito il Lago d'Averno e i Campi Flegrei nel corso dei secoli (pensiamo, ad esempio, al sisma del 1538, in concomitanza del quale un piccolo vulcano, il Monte Nuovo, si innalzò dalla terra nel corso di una manciata di giorni).

Malgrado ciò, Strabone, che scrive nel primo secolo, ci rende disponibile un dettaglio aggiuntivo di grande rilevanza (Fig. 2):

«Successivamente i Cimmèri furono distrutti da un certo re, al quale i responsi oracolari non risultarono graditi; ma la sede dell'oracolo esiste ancora oggi, benché essa sia stata trasferita in altro luogo».

[Nella traduzione latina dall'originale greco: «postea temporis Cimmerios fuisse deletos a rege quodam, cuius eventa oraculum non comprobassent, sedem oraculi alio translatam etiamnun durare»].

È possibile ipotizzare che la Sibilla Cimmeria, la quale forniva responsi oracolari presso un sito sotterraneo nell'area di Cuma, interrogando i morti tramite pratiche negromantiche, abbia subìto un trasferimento presso un altro e diverso santuario, situato nella medesima area cumana, a seguito della distruzione della propria sede originale, e che il nome assunto dalla Sibilla nel nuovo sito sia proprio 'Cumana'?

È possibile che l'antica, originale Sibilla Cimmeria abbia acquisito il nome finale di 'Sibilla Cumana', dopo l'abbandono del proprio precedente sito sotterraneo, a causa dell'obliterazione dello stesso?

Secondo molti studiosi, la risposta a queste domande sarebbe positiva. Jacques Hergon, un celebre latinista francese, e altri ricercatori (Luca Antonelli) considerano la Sibilla Cimmeria come la più antica profetessa attiva nell'area cumana, operante con tecniche di tipo negromantico. In seguito, dopo la distruzione del tempio sotterraneo originale, l'oracolo si sarebbe trasferito in un diverso sito posto nell'area centrale di Cuma, assumendo il nome di 'Sibilla Cumana' e rendendo le proprie profezie mediante scrittura di vaticini eseguita su di una pluralità di foglie di quercia, abbandonate poi al libero gioco del vento («volent rapidis ludibria ventis», come racconta Virgilio), in modo tale da rendere il responso oracolare sostanzialmente incomprensibile.

Dunque, la Sibilla Cimmeria e la Sibilla Cumana non sarebbero altro che la medesima profetessa, la prima rappresentando semplicemente il nome più antico della seconda.

Questa identificazione sarebbe in grado di spiegare in modo del tutto esaustivo quella sospetta confusione tra i vari appellativi attribuiti alla quarta Sibilla, così come indicati nelle differenti versioni dell'antica enumerazione delineata da Lattanzio: 'Cimmeria', secondo alcune di esse, e 'Cumana' in altri manoscritti. Secondo questa ipotesi, la quarta Sibilla sarebbe fondamentalmente identica alla settima, la Cumana, ma ad essa sarebbe attribuito il nome originale e più antico.

E anche un altro peculiare enigma letterario, connesso alla descrizione della Sibilla Cumana così come proposta da Virgilio nella sua "Eneide", potrebbe trovare, in questo modo, la propria corretta soluzione.

Nel libro VI, Virgilio racconta di come, dopo il suo arrivo a Cuma, «il pio Enea ascenda la cittadella, retta dal glorioso Apollo, recandosi all'antro profondo, orrendo e appartato della Sibilla» («pius Aeneas arces, quibus altus Apollo presidet horrendaque procul secreta Sibyllae antrum immane petit» in latino). Egli sta per visitare quella che deve essere identificata come la Sibilla Cumana, la quale fornisce i propri responsi esprimendo la voce e la volontà del dio greco Apollo:

«Tali sono le redini che Apollo scuote nella furente profetessa, e tali gli speroni che il dio le urge nel petto».

[Nel testo originale latino: «ea frena furenti concutit et stimolos sub pectore vertit Apollo»].

Ma poi, successivamente, nel medesimo libro, la Sibilla ordina a Enea di presentare un'offerta a Ecate, la dea greca associata alla stregoneria e alla negromanzia, e il rituale viene posto in atto in una grotta posta presso il Lago d'Averno. Ora, la Sibilla ha assunto tutti gli attributi della più antica profetessa Cimmeria:

«Una profonda spelonca era lì, una vasta, immensa fenditura, difficile da penetrare, protetta dal lago nero e dalla tenebra delle selve [... Enea] pone l'offerta sul fuoco sacro, dono copioso, evocando Ecate con la propria voce, invocando i cieli e il vasto Erebo».

[Nel testo originale latino: «Spelunca alta fuit vastoque inmanis hiatu, scrupea, tuta lacu nigro nemoremque tenebris [...] ignibus imponit sacris, libamina prima, voce vocans Hecaten caeloque Ereboque potentem»].

Nei brani qui citati, Virgilio non starebbe facendo altro che porre in scena i due differenti aspetti della Sibilla Cimmeria / Cumana: la profetessa che si avvale di arti negromantiche (Cimmeria) e l'oracolo di Apollo (Cumana). Due diverse rappresentazioni della stessa Sibilla: la Sibilla di Cuma.

Una Sibilla che riemerge dalle nebbie di un passato perduto e quasi dimenticato, così come rappresentata nel preziosissimo manoscritto miniato dell''Eneide' (Vat Lat 3225) conservato presso la Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana: uno dei reperti manoscritti più antichi dell'intero mondo classico romano, risalente addirittura al quarto secolo, con una stupenda immagine di Enea e del suo compagno Acate raffigurati mentre si presentano innanzi alla Sibilla Cumana e al suo tempio apollineo (Fig. 1).

Ci stiamo avvicinando sempre di più al termine del nostro incredibile viaggio attraverso il mito e le tradizioni sibilline. È giunto ora il momento di rispondere alla domanda iniziale, quella che ci eravamo posti quando abbiamo cominciato il nostro percorso: la Sibilla Appenninica, la Sibilla di Norcia, è forse collegata in qualche modo con la Sibilla Cimmeria, così come sostenuto da un abate siciliano vissuto nel sedicesimo secolo, Francesco Maurolico, nella sua “Topographia Sanctorum Christi Martyrum”?

La risposta, adesso, ci appare assolutamente chiara. E andremo ad esplicitarla nel prossimo articolo.

9 Jul 2018

A Sibyl called Cimmerian: exploring the potential link to the Apennine Sibyl - 9. Cumaen and Cimmerian, a single Sibyl for Cumae

Cumae, one of the most ancient Greek colonies in southern Italy, established at the mid of the eighth century B.C., a town that was regarded as sacred to ctonian deities owing to its highly peculiar volcanic nature.

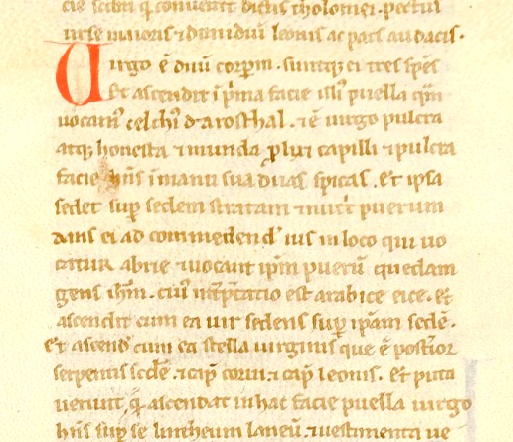

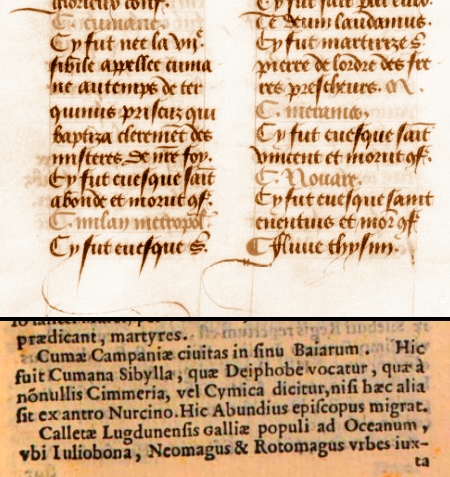

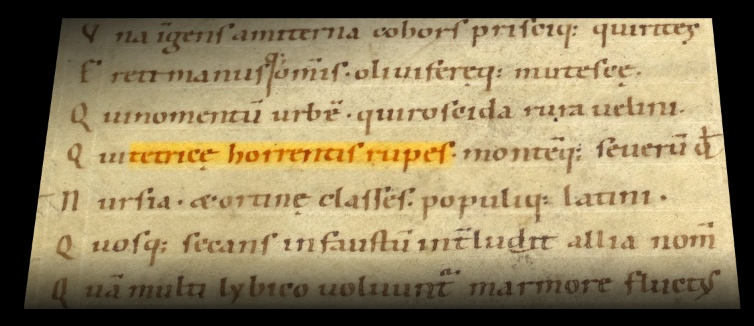

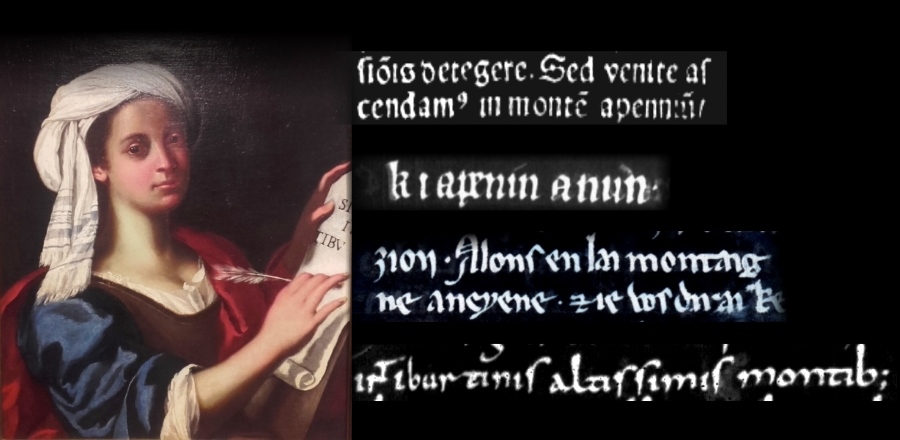

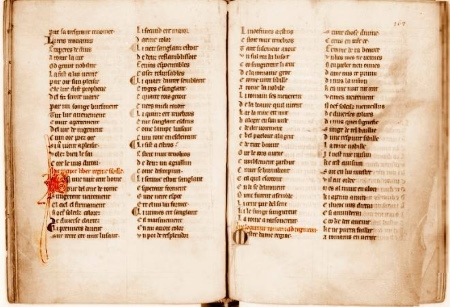

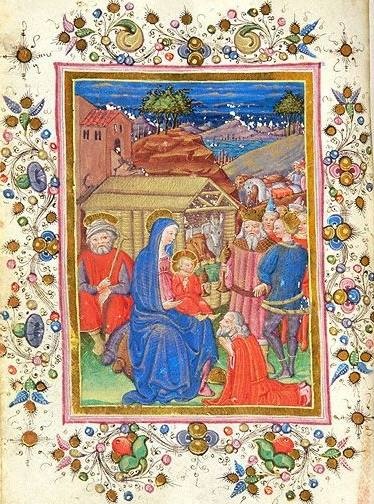

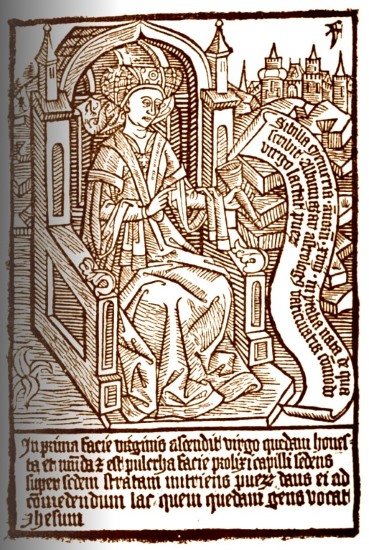

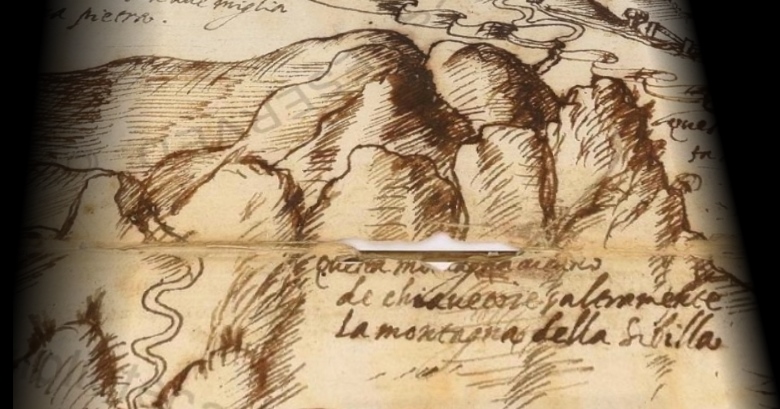

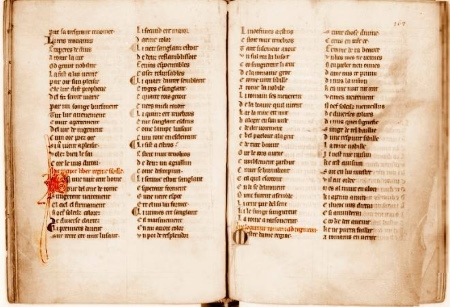

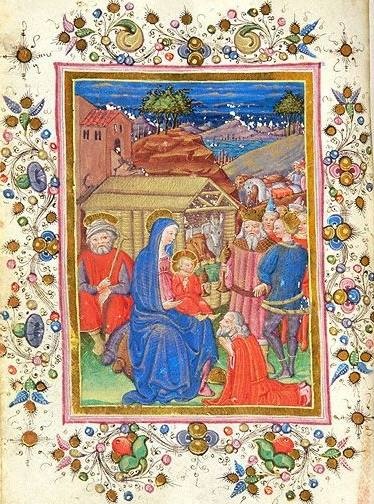

As we saw already, according to the available documents describing the traditions of ancient Rome, two sibilline oracles were to be found in Cumae: the Cumaean Sibyl and the Cimmerian Sibyl (both portrayed in Fig. 1 as they appear in a most precious Book of Hours dating to year 1427, preserved at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in manuscript Latin 920).

Were they different Sibyls? Did they have any relationship one another? And are there any visible remnants of their shrines? What do contemporary archeology and modern history research have to tell us about them?

Let's consider the most famous prophetess, the Cumaean Sibyl: the seventh oracle in Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius' classical list. She was also celebrated by Vergilius in Book 6 of “Aeneid” with masterful verses: «terrific riddles she yells, as she sings in her cave, the truth enshrouded in darkness» [«Cumaea Sibylla - horrendas canit ambages antroque remugit - obscuris vera involvens» in Latin]. And we cannot forget the amazing portrait of a withered, ever-ageing Sibyl subject to a doom of immortality, as provided to us by Publius Ovidius Naso in his “Metamorphoses”, with a final stroke being painted by Gaius Petronius Arbiter, in his “Satyricon”, in which a shrunken Cumaean Sibyl, confined in a flask, asks visitors for a merciful death.

The literary tradition on the Cumaean Sibyl seems unmistakable, and it appears to depict some sort of oracle that really existed in ancient times.

However, the topic is not so easily managed. The Sibyl's Cave discovered in Cumae by an Italian archeologist, Amedeo Maiuri, in 1932 and shown to visitors in our present days is not recognised by scholars as the veritable site where the Cumaean Siby vaticinated. No archeological evidence of such an attribution has ever been found at the place. No positive, glaring oracular site has yet been identified in the existing area of ancient Cumae.

The actual problem is that, already in antique times, the Cumaean Sibyl was not active anymore. When Vergilius, Ovidius, Petronius and Lactantius wrote their works, the Sibyl had long transfomed herself into a remote legend, lost in the mists of the past. Romans never knew nor saw this Sibyl in her actual reality, for she belonged to the long-gone Greek past of Cumae, a town which the Romans conquered in year 338 B.C., four hundred years after its foundation. Rieuwerd Buitenwerf, a Dutch scholar, says with an incisive remark on the Cumaean oracle that «its location had already been forgotten by the time Virgil visited Cumae».

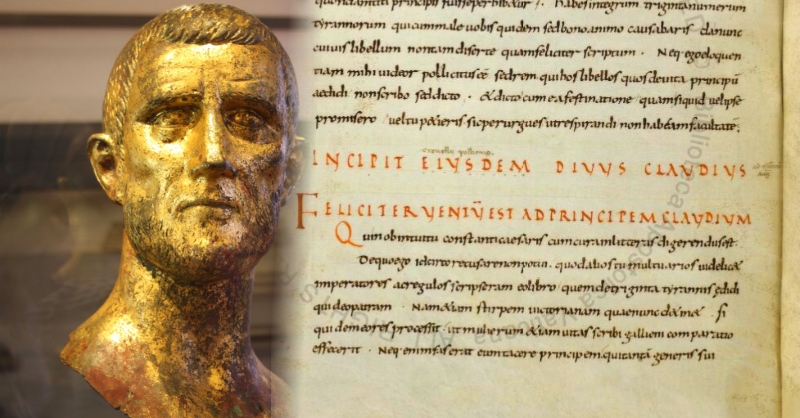

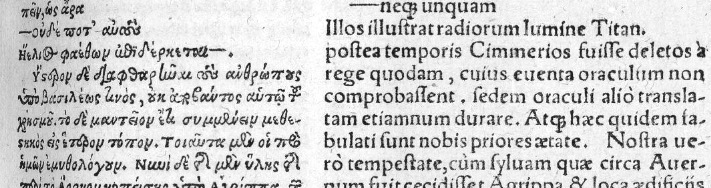

In the fourth century of the Christian era, Cumae had become a celebrated attraction for turists who - just as today - wanted to see the site of the legendary Sibyl chanted by Vergilius. And sure enough the locals did not restrain themselves from telling paying visitors what they wanted to hear, as narrated in the “Exhortation to the Greeks” (Chapter 39 - see Fig. 2), a Greek text once attributed to St. Justin Martyr:

«Easily you will learn the right religion from the ancient Sibyl, who used to teach through some kind of amazing inspiration by means of oracular predictions. [...] She, they say, rendered her prophecies in a city called Cumae, six miles from Baiae (where the hot springs of Campania are found). When we arrived in this city, we saw a certain place where we discerned a huge basilica, hewn out of one rock [...] People who had received the local tradition from their own ancestors, told us that this was the very place where the prophetess used to utter her oracles. [...] When we were in the city, we learned this things ourselves from the ones who use to guide the visitors around to see the remarkable places in the area. They showed us also [...] a small artifact, made of bronze, in which they said her remains were kept».

[In the Latin translation from the original text in Greek: «Perfacile autem vobis erit rectam religionem [...] a veteri Sibylla ex afflatu quodam mirifico per sortes ac responsa vos docente percipere. [...] Eam in Campaniae [...] in urbe quadam cui Cumae nomen est, sexto a Baiis (qui locus thermas Campanas habet) lapide, oracula edidisse. Vidimus nos ea in urbe cum essemus, locum quendam, in quo ingentem basilicam, uno fabrefactam saxo contemplati sumus [...] ubi responsa eam dedisse affirmabant illi, qui res patrias a majoribus suis traditas acceperint. [...] Quin ipsi quoque, cum in ube ea essemus, indicibus, qui hospites ad ea, quae visenda sunt, ducere solent, ostendentibus [...] vidimus loculum quendam ex aere elaboratum ubi reliquias ejus servari dicebant»].

So the actual, physical reality of the Cumaean Sibyl and her shrine appears to be lost forever, and that loss had already taken place at the time when Romans won Cumae for themselves.

And now, what about the Cimmerian Sibyl? If we start considering the Sibyl of the Cimmerians, the mist of history turns out to be even thicker. Let's try to dispel it, at least partially, in the next article.

Una Sibilla chiamata Cimmeria: un'investigazione sulla possibile relazione con la Sibilla Appenninica - 9. Cumana e Cimmeria, una sola Sibilla per Cuma

Cuma, una delle più antiche colonie greche nell'Italia meridionale, fondata a metà dell'VIII secolo a.C., una città che fu considerata come sacra alle divinità ctonie a causa della peculiarissima natura vulcanica di quel territorio.

Come abbiamo avuto modo di vedere, sulla base della documentazione disponibile relativamente alle tradizioni di Roma antica, Cuma ospitava due specifici oracoli sibillini: la Sibilla Cumana e la Sibilla Cimmeria (entrambe rappresentate in Fig. 1 così come appaiono in un preziosissimo Libro delle Ore risalente all'anno 1427, conservato presso la Bibliothèque Nationale de France all'interno del manoscritto Latin 920).

Si trattava veramente di oracoli differenti? Esisteva una relazione tra di essi? Esistono ancora resti visibili dei relativi luoghi di culto? Cosa possono raccontarci oggi, di esse, l'archeologia e le moderne ricerche storiche?

Prendiamo in esame la profetessa di maggior fama, la Sibilla Cumana: il settimo oracolo, nell'elencazione classica di Lucio Cecilio Firmiano Lattanzio. Essa fu anche celebrata da Virgilio nel sesto libro dell'"Eneide", con versi immortali: «enigmi paurosi essa canta mugghiando nell’antro, la verità avvolgendo di tenebra» [«Cumaea Sibylla - horrendas canit ambages antroque remugit - obscuris vera involvens» in latino]. E non possiamo nemmeno dimenticare l'impressionante immagine di una Sibilla decrepita e soggetta ad un invecchiamento senza fine, tramandataci da Publio Ovidio Nasone nelle sue "Metamorfosi", con un tocco finale dipinto per noi da Gaio Petronio Arbitro, nel suo "Satyricon", nel quale una Sibilla Cumana ormai avvizzita e ridotta ad un essere minuscolo, confinata in un'ampolla, implora i suoi visitatori affinché le sia finalmente concessa una morte misericordiosa.

La tradizione letteraria concernente la Sibilla Cumana appare dunque indubitabile, e pare effettivamente che essa descriva una qualche tipologia di oracolo realmente esistente in tempi molto antichi.

Eppure, l'intera materia non pare affatto presentarsi come definitivamente consolidata. L'Antro della Sibilla scoperto a Cuma nel 1932 da un archeologo italiano, Amedeo Maiuri, e mostrato oggi ai turisti non è affatto riconosciuto dagli studiosi come l'autentico sito presso il quale la Sibilla Cumana rendeva i propri vaticini. Nessuna evidenza archeologica in grado di confermare questa attribuzione è stata mai reperita nei locali sotterranei. E nessun sito manifestamente, indubitabilmente oracolare è stato mai identificato nell'attuale area dell'antica Cuma.

Il vero problema, infatti, è che già nell'antichità la Sibilla Cumana non era più attiva da lungo tempo. Quando Virgilio, Ovidio, Petronio e Lattanzio scrivono le rispettive opere, la Sibilla ha già compiuto la propria trasformazione da oracolo a leggenda nebulosa e remota, perduta tra le nebbie del passato. I Romani non conobbero né videro mai questa Sibilla nella sua tangibile realtà, in quanto essa già apparteneva, ormai, al lontano passato della Cuma greca, che fu conquistata dai Romani nell'anno 338 a.C., quattrocento anni dopo la fondazione dell'insediamento. Rieuwerd Buitenwerf, uno studioso olandese, afferma con un'incisiva osservazione a proposito dell'oracolo cumano che «la sua esatta localizzazione era stata già da tempo dimenticata all'epoca in cui Virgilio visitò Cuma».

Nel quarto secolo dell'era cristiana, Cuma si era già trasformata in una rinomata attrazione per i turisti dell'epoca, i quali - esattamente come accade anche oggi - volevano visitare il luogo dove aveva profetato la leggendaria Sibilla cantata da Virgilio. E la gente del luogo non si tirava certamente indietro nel narrare ai visitatori paganti ciò che essi volevano sentirsi dire, come ci viene raccontato nell'"Esortazione ai Greci" (Capitolo 39 - vedere Fig. 2), testo in lingua greca attribuito a S. Giustino Martire:

«Facilmente apprenderai la retta religione [...] dall'antica Sibilla, che insegnò attraverso una sorta di mirabile ispirazione per mezzo di responsi oracolari [...] Si racconta di come essa rendesse le proprie profezie in una certa città chiamata Cuma, a sei miglia da Baia (dove si trovano le acque calde della Campania). Quando giungemmo in città, visitammo un certo luogo nel quale si poteva vedere una grande basilica, tagliata all'interno di una grande roccia [...] La gente, alla quale era stata tramandata questa tradizione locale dai propri avi, ci raccontò che questo era il luogo in cui la profetessa era solita pronunciare i propri oracoli. [...] Quando fummo in città, potemmo apprendere queste cose da coloro che erano soliti fare da guida ai visitatori, per mostrare loro i luoghi notevoli. [...] Ci mostrarono anche [...] un piccolo contenitore, fatto di bronzo, all'interno del quale essi affermavano che fossero ancora custoditi i suoi resti».

[Nella traduzione latina dal testo greco originale: «Perfacile autem vobis erit rectam religionem [...] a veteri Sibylla ex afflatu quodam mirifico per sortes ac responsa vos docente percipere. [...] Eam in Campaniae [...] in urbe quadam cui Cumae nomen est, sexto a Baiis (qui locus thermas Campanas habet) lapide, oracula edidisse. Vidimus nos ea in urbe cum essemus, locum quendam, in quo ingentem basilicam, uno fabrefactam saxo contemplati sumus [...] ubi responsa eam dedisse affirmabant illi, qui res patrias a majoribus suis traditas acceperint. [...] Quin ipsi quoque, cum in ube ea essemus, indicibus, qui hospites ad ea, quae visenda sunt, ducere solent, ostendentibus [...] vidimus loculum quendam ex aere elaboratum ubi reliquias ejus servari dicebant»].

E così la presenza reale, attuale della Sibilla Cumana e del suo tempio oracolare pare ormai essere andata perduta per sempre, e questa perdita aveva già avuto luogo quando i Romani conquistarono Cuma per se stessi.

E la Sibilla Cimmeria? Se adesso cominciamo a prendere in considerazione la Sibilla dei Cimmèri, le nebbie della storia non possono che apparire ancor più fitte di fronte ai nostri occhi. Proviamo a disperderle, almeno in parte, nel prossimo articolo.

3 Jul 2018

A Sibyl called Cimmerian: exploring the potential link to the Apennine Sibyl - 8. Cumae, a land of netherworld gods

After a close scrutiny of a number of ancient literary sources, we found out that the Cimmerian Sibyl belongs to the area of the Lake Avernus, in the Italian region of Campania: only a mile away from the traditional site where the Cumaean Sibyl is said to have rendered her oracular responses by the ancient town of Cumae.

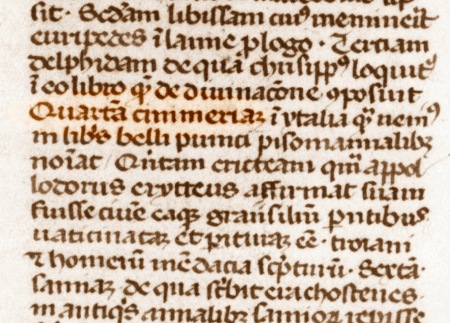

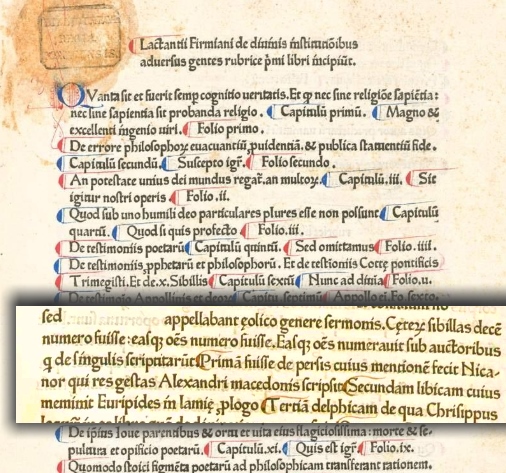

This result - which is already well known by scholars - should not be considered as unexpected. When we started our investigation, we noted, as many scholars did in the past, that in the classical enumeration of ten oracles set down by Lactantius the seventh Sibyl was the Cumaean («Cumana» in Latin), and the fourth the Cimmerian; however, in some versions of Lactantius' “De Divinis Institutionibus” the fourth oracle appears with the attribute “Cumean”: a name that cannot but remind us of the antique town of Cumae, and an attribute providing a strong clue as to where to direct our research efforts.

And finally we caught the Cimmerian Sibyl in very region of Cumae. But why should there be two different Sibyls in the same area, a Cumaen and a Cimmerian?

First, we have to bear in mind the utterly peculiar nature of this portion of Italian land.

Let's fly over this corner of Campania, in southern Italy, by considering the attached map: we are hovering on a territory which is heavily, permanently marked by the mightiest subterranean powers in Europe. A land blessed - and doomed - by the Gods of the Netherworld.

Eastward of Cumae and Cape Misenus, since time immemorial, the ground has been ravaged by the fury of volcanoes. We are in the most renowned Phlegraean Fields, a large volcanic area hiding one of the most dangerous, and still active today, subterranean magmatic chambers in the world.

The Lake Avernus itself, at the center of the image, is a volcanic crater lake, once encircled by gloomy hills covered with mysterious woods. Strabo says that «the birds that cross the lake fall down into the waters, being killed by the vapours that rise from it, as it happens for places which are linked to the Netherworld» («aves quae supervolarent in aquam decidere, exanimatas aeris exhalatione, quemadmodum i Plutonijs locis fit» in Latin). A number of additional volcanic calderas (Mount Barbaro, the large Astroni crater, and many others) are present in the top side of the picture, including the small yet impressive Monte Nuovo ('The New Mountain'), a tiny volcano which was created from nothing by a sudden eruption which took place between September, 29 and October, 6 1538. Earthquakes, emission of volcanic gases and measurable displacements of the ground (a phenomenon known as 'bradyseism') have always happened there.

No wonder that this land has always been considered as sacred to subterranean, divine powers. In Book 6 of his “Aeneid”, Publius Vergilius Maro sends Aeneas to the shore of Cumae, in search of the entryway to the underworld, «protected by the gloomy lake and the darkness of the woods» («tuta lacu nigro nemorumque tenebris» in Latin). And, according to many scholars, Lake Avernus was actually seen by ancient Romans as the entrance to Hades.

In this highly evocative context were rooted two different sibilline tradition: the Cumaean oracle and the Cimmerian oracle. However, both traditions, though documented through many literary passages drawn from a number of Latin and Greek authors, are not so easy to pinpoint from a storical and archeological points of view, as we will see in the next article.

Una Sibilla chiamata Cimmeria: un'investigazione sulla possibile relazione con la Sibilla Appenninica - 8. Cuma, terra di dèi inferi

Dopo avere attentamente esaminato una pluralità di fonti letterarie antiche, abbiamo scoperto come la Sibilla Cimmeria sia appartenuta all'area del Lago di Averno, situata nella regione chiamata Campania: ad un solo miglio di distanza dal sito tradizionale presso il quale si ritiene che la Sibilla Cumana rendesse i propri responsi oracolari, nell'antica città di Cuma.

Questo risultato - già ben noto agli studiosi - non dovrebbe essere considerato come del tutto inatteso. Quando abbiamo dato inizio alla nostra investigazione, abbiamo potuto osservare, come già notato in passato da molti ricercatori, come nella classica enumerazione redatta da Lattanzio e concernente dieci oracoli la settima Sibilla fosse la Cumana, e la quarta la Cimmeria; eppure, in alcune versioni del "De Divinis Institutionibus" di Lattanzio, la quarta Sibilla appare con l'attributo di "Cumaea": un appellativo che non può non riportare alla nostra mente l'antico nome di Cuma, fornendoci così un potente indizio utile ad identificare verso quale direzione volgere la nostra ricerca.

E, finalmente, siamo riusciti a rintracciare la Sibilla Cimmeria esattamente nell'area di Cuma. Ma come è possibile che vi fossero due differenti Sibille nella medesima area, una Cumana e una Cimmeria?

Come prima cosa, dobbiamo fissare bene in mente quale sia la peculiarissima natura di questa porzione della terra d'Italia.

Proviamo a volare insieme su questo angolo di Campania, nell'Italia meridionale, prendendo in considerazione la mappa qui allegata: stiamo sorvolando un territorio che è pesantemente e permanentemente marcato dalle più maestose potenze sotterranee dell'intera Europa. Una terra benedetta - e maledetta - dagli Dèi Inferi.

Ad est di Cuma e Capo Miseno, sin da tempo immemorabile, la terra è stata devastata dalla furia dei vulcani. Ci troviamo nei celeberrimi Campi Flegrei, una vasta regione vulcanica che nasconde una delle più pericolose, e del tutto attive ai nostri giorni, camere magmatiche sotterranee dell'intero globo.

Lo stesso Lago di Averno, al centro dell'immagine, è un lago formatosi all'interno di un cratere vulcanico, un tempo circondato da tenebrose colline ricoperte da boschi spaventevoli. Strabone racconta di come «gli uccelli che lo sorvolavano piombassero nell'acqua, uccisi dalle esalazioni di quei vapori, così come accade nei luoghi consacrati a Plutone» («aves quae supervolarent in aquam decidere, exanimatas aeris exhalatione, quemadmodum i Plutonijs locis fit» in Latino). E ulteriori, numerose caldere vulcaniche (Monte Barbaro, il grande cratere degli Astroni, e molti altri) sono inoltre presenti nella porzione superiore dell'immagine, compreso il piccolo ma impressionante Monte Nuovo, un minuscolo vulcano formatosi dal nulla in conseguenza di un'improvvisa eruzione che ebbe luogo tra il 29 settembre e il 6 ottobre 1538. Terremoti, emissione di gas vulcanici e sensibili spostamenti verticali del terreno (un fenomeno denominato 'bradisismo') hanno avuto luogo in questa zona da sempre.

Non c'è dunque da meravigliarsi se questa terra sia stata da sempre considerata come sacra alle divine potenze del sottosuolo. Nel Libro 6 dell'"Eneide", Publio Virgilio Marone invia Enea fino alle spiagge di Cuma, in cerca dell'ingresso al mondo sotterraneo dei morti, «guardato dal nero lago e dall'oscurità delle selve» («tuta lacu nigro nemorumque tenebris» in Latino). E, secondo molti studiosi, il Lago Averno era effettivamente considerato dagli antichi Romani come il punto di ingresso all'Ade.

In questo contesto così altamente evocativo hanno avuto modo di radicarsi ben due differenti tradizioni sibilline: l'oracolo Cumano e quello Cimmerio. Eppure, nessuna delle due tradizioni - benché entrambe risultino essere menzionate in vari brani letterari tratti da diversi autori sia greci che latini - sembra essere facilmente documentabile dal punto di vista storico e archeologico, come avremo modo di vedere nel prossimo articolo.

1 Jul 2018

A Sibyl called Cimmerian: exploring the potential link to the Apennine Sibyl - 7. A subterranean Sibyl at the Lake Avernus

By following the footprints left by the Cimmerian Sibyl throughout the centuries, we have come back to the classical age, when southern Italy was the magical scenario for colonies established by settlers moving from Greece.

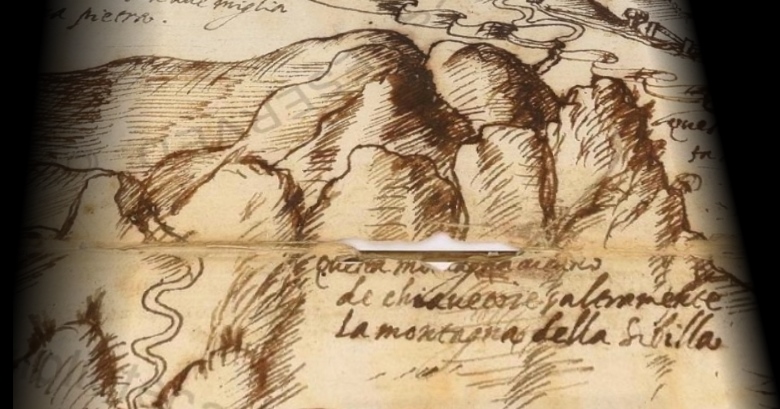

In the seaside region set between Cumae, Mount Procida with Cape Misenus, Baiae and Pozzuoli, lay an area which was the realm of mighty subterranean powers: a volcanic area, fully active at that times as it is today, and where the gloomy Lake Avernus stood (see Fig. 1), surrounded by looming hills and protected by an impenetrable forest. There, an antique population had their abode, the Cimmerians, who lived in subterranean dwellings.

And they served an oracle, hidden from view and set under the ground. An oracle which vaticinated by querying the dead, as Strabo recounts in his “Geographica”:

«Those who lived prior to our age applied to Lake Avernus the fairy tale about necromancy which is found in Homer, and so much so that they thought here was the oracle where the dead uttered prophecies as if they were alive: the oracle to which Ulysses came».

[In the Latin translation from the original Greek text: «Qui nos aetate antecesserunt, Necyae Homericae fabulas Averno applicaverunt, atque adeo narrant fuisse ibi oraculum ubi vita defuncti responsa darent, eoque Ulissem advenisse»].

But who provided a bridge between the world of the dead and the living men who asked for responses?

It was a Sibyl.

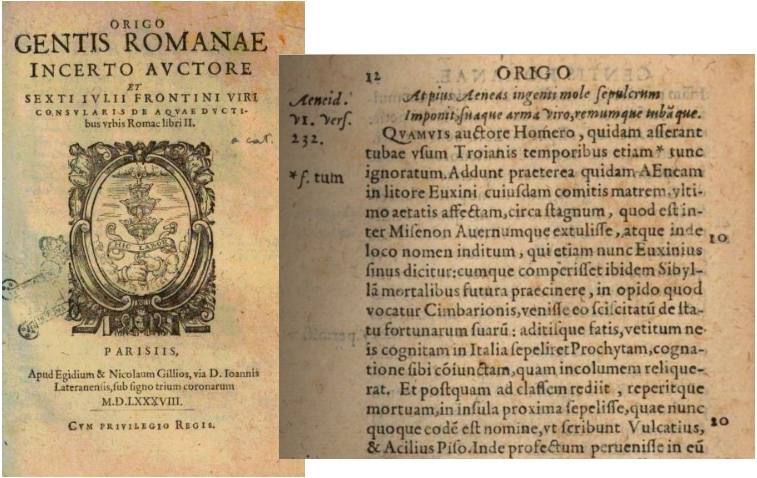

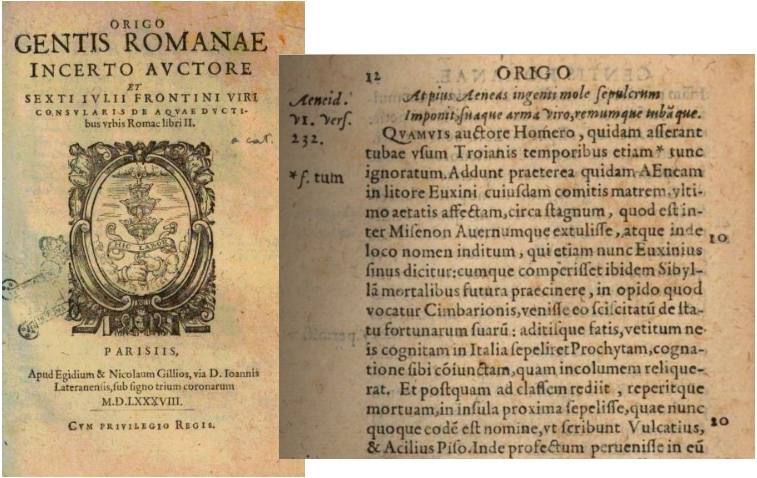

Let's read from a remarkable excerpt taken from “Origo Gentis Romanae” (“The Origin of Roman People”), a fourth-century work attributed to Latin author Sextus Aurelius Victor. The passage depicts Aeneas after his arrival to Italy following the destruction of Troy:

«Aeneas buried on the shore the mother of Euxinus, one of his comrades, who had been carried off by old age, around the marsh which is between Misenus and Avernus, and that, thence, the name was assigned to the spot. And when he had discovered that in that very place a Sibyl chanted future events to mortals in the city which is called Cimbarionis, [they add that] he came to it, having inquired about the state of his own fortunes, and having been forbidden to bury in Italy his relative Prochyta, related to him by blood, whom he had left in good health. And afterwards he returned to the fleet and found she was dead in actual truth...».

[In the original Latin text: «Aeneam in eo litore Euxini cuiusdam comitis matrem ultime aetatis affectam circa stagnum, quod est inter Misenon Avernumque, extulisse atque inde loco nomen inditum; cumque comperisset ibidem Sibyllani mortalibus futura praecinere in oppido, quod vocatur Cimbarionis, venisse eo sciscitatum de statu fortunarum suarum aditisque fatis vetitum, ne is cognatam in Italia sepeliret Prochytam, cognatione sibi coniunctam, quam incolumem reliquerat. Et postquam ad classem rediit repperitque mortuam...»].

In the town of Cimmerians («Cimbarionis» in Strabo), hidden beneath the ground and set between Cape Misenus and the Lake of Alvernus, there was a Sibyl, who vaticinated through the responses given by the dead.

At last, we have found the Cimmerian Sibyl: she was another Italian Sibyl, included in the classical list set down by Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius, also including two other Sibyls from Italy, namely the Cumaean and the Tiburtine. And her abode was under the hills of Lake Avernus, not far from Cumae and Naples.

But what about the Cumaean Sibyl, whose shrine was also present in the very same area? And what about the alleged relationship - as stated by Francesco Maurolico in the sixteenth century - between the Cimmerian and the Apennine Sibyl, who was set in an utterly different region of Italy? Now, it seems to us that the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle are all coming together, and they indicate that no relation can be highlighted between the two Sibyls.

We will try to disentagle the above remaining questions in the next article.

Una Sibilla chiamata Cimmeria: un'investigazione sulla possibile relazione con la Sibilla Appenninica - 7. Una Sibilla nel sottosuolo presso il Lago d'Averno

Seguendo le orme lasciate dalla Sibilla Cimmeria nel corso dei secoli, siamo tornati indietro nel tempo sino all'età classica, quando l'Italia meridionale era un territorio dai magici scenari per i molteplici insediamenti ivi stabiliti dai coloni provenienti dalla Grecia.

Nella zona costiera posta tra Cuma, il Monte Procida e il Capo Miseno, Baia e Pozzuoli, si trovava una regione che era il regno misterioso abitato da immani potenze sotterranee: un'area vulcanica, viva e attiva oggi come allora, dove si trovava il tenebroso Lago d'Averno (Fig. 1), circondato da incombenti colline e protetto da una foresta impenetrabile. Proprio lì aveva la propria dimora un popolo antico, i Cimmèri, i quali vivevano nel sottosuolo.

E questo popolo serviva un oracolo, nascosto alla vista e posto nel sottosuolo. Un oracolo che vaticinava interrogando i morti, così come ci racconta Strabone nella sua opera “Geographica”:

«Coloro che vissero prima di noi, considerarono il Lago d'Averno come il luogo in cui si svolge il leggendario episodio della negromanzia raccontato da Omero, tanto da narrare come si trovasse proprio lì l'oracolo che otteneva responsi dai morti come se essi fossero vivi: lo stesso oracolo al quale si rivolse Ulisse».

[Nella traduzione latina dall'originale Greco: «Qui nos aetate antecesserunt, Necyae Homericae fabulas Averno applicaverunt, atque adeo narrant fuisse ibi oraculum ubi vita defuncti responsa darent, eoque Ulissem advenisse»].

Ma chi era a stabilire la comunicazione tra il mondo dei morti e quello dei vivi, uomini mortali in cerca di oracolari responsi?

Si trattava di una Sibilla.

Andiamo infatti a leggere un significativo passaggio tratto dall'“Origo Gentis Romanae”, un'opera del quarto secolo attribuita all'autore latino Sesto Aurelio Vittore. Il brano racconta di Enea, l'eroe troiano appena giunto in Italia dopo la distruzione della sua città e della sua gente:

«Enea seppellì su quella spiaggia la madre di Eusino, uno dei suoi compagni, deceduta a causa dell'età avanzata; la seppellì vicino alla palude che si trova tra Miseno e l'Averno, ed ecco da dove quel luogo trasse il proprio nome. E quando venne a sapere che nel villaggio, chiamato Cimbarione, una Sibilla cantava ai mortali il futuro, egli vi si recò e, avendo chiesto un responso a proposito del suo stesso destino, ed essendogli stato proibito di seppellire in Italia la sua congiunta Prochyta, a lui consanguinea, che egli aveva lasciato in buona salute, si affrettò a tornare presso la flotta, e trovò che veramente ella era morta...».

[Nel testo originale latino: «Aeneam in eo litore Euxini cuiusdam comitis matrem ultime aetatis affectam circa stagnum, quod est inter Misenon Avernumque, extulisse atque inde loco nomen inditum; cumque comperisset ibidem Sibyllani mortalibus futura praecinere in oppido, quod vocatur Cimbarionis, venisse eo sciscitatum de statu fortunarum suarum aditisque fatis vetitum, ne is cognatam in Italia sepeliret Prochytam, cognatione sibi coniunctam, quam incolumem reliquerat. Et postquam ad classem rediit repperitque mortuam...»].

Nella città dei Cimmèri («Cimbarionis» in Strabone), nascosta nel sottosuolo e posta tra Capo Miseno e il Lago d'Averno, operava una Sibilla, che profetava per mezzo di responsi ottenuti interrogando le anime dei morti.

Siamo riusciti dunque, finalmente, ad arrivare fino alla Sibilla Cimmeria: essa era un'ulteriore Sibilla italica, inclusa nell'elencazione classica definita da Lucio Cecilio Firmiano Lattanzio, che comprendeva anche due ulteriori Sibille originarie dell'Italia, la Cumana e la Tiburtina. E la sua dimora si trovava al di sotto delle colline che circondavano il Lago d'Averno, non lontano da Cuma e Napoli.

E la Sibilla Cumana? Cosa possiamo dire a proposito di questa Sibilla, il cui tempio oracolare era anch'esso presente proprio nella medesima area? E cosa possiamo ora affermare in merito alla supposta connessione - così come rivendicata da Francesco Maurolico nel sedicesimo secolo - tra la Sibilla Cimmeria e quella Appenninica, la cui dimora si trova invece in una regione d'Italia totalmente differente? Sembrerebbe proprio, adesso, che tutti i pezzi del rompicapo comincino ad incastrarsi tra loro, e ciò i vari elementi reperiti cominciano ad indicare non pare che vadano a stabilire alcuna relazione tra le due Sibille.

Proveremo a rispondere a queste intricate questioni nel prossimo articolo.

29 Jun 2018

A Sibyl called Cimmerian: exploring the potential link to the Apennine Sibyl - 6. The Cimmerians and their oracle

We are still on the footsteps of the Cimmerian Sibyl, the fourth oracle mentioned in the classical enumeration provided by Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius in the fourth century. A Sibyl that in some versions of Lactantius “De Divinis Institutionibus” is presented as “Cumean”, a word that brings to the mind of the reader the word 'Cumae', the Campanian town of the Cumaean Sibyl, who in turn is listed under number seven in Lactantius' list.

So the main question now is: where is the Cimmerian Sibyl from? According to Francesco Maurolico, a sixteenth-century Sicilian author, she would reside by a town called «Ameria» or a village named «Cimerio» lying by the caves of Norcia, so the Cimmerian Sibyl and the Apennine Sibyl would actually be the very same oracle.

But only Maurolico (and a Father Fortunato Ciucci from Norcia, who quotes from Maurolico in the seventeenth century) supports this assumption.

No other similar identification is retrieved in other authors or works, either in the main sources used by Maurolico (the “Mappemonde Spirituelle” by Jean Germain, which we saw in a previous paper) or the “Oracula Sibyllina” and Filippo Barbieri's “Opuscula”.

So, if we want to find the truth, we have no choice left: we have to turn back and return to classical authors.

The key to all that is the nature and identity of the people known as 'Cimmerians'. Today, many people think that Cimmerians were an ancient tribal population who lived in the Caucasus. In fact they are mentioned by the Greek historian Herodotus, and have become part of a wider, contemporary popular culture through the fictional tales of Conan the Cimmerian, written by American author Robert E. Howard, in which Cimmerians are depicted as an offspring of a Celtic, northern-European culture.

But this is only a minor tradition, though the most widely known, concerning the Cimmerians.

Because if we look for Cimmerians in classical literature, we find no Celts and no Caucasus at all: instead, we are transported back to a place we already know. We know it well, owing to a most famous Sibyl.

And this place is Cumae.

Because, if the works by ancient writers such as Gnaeus Naevius and Lucius Calpurnius Piso Frugi - who mentioned the Cimmerian Sibyl as Lactantius indicates- are unfortunately lost to us, nonetheless there are still other ancient authors whose works survive. And they all tell unanimously the same story: Cimmerians lived in southern Italy, namely near Cumae (Fig. 1 - Ancient Cumae in a map detail taken from the Tabula Peutingeriana, a thirteenth-century copy on parchment of an original Roman road map - Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Codex Vindobonensis 324).

Let's listen to the ancient voices which narrate this amazing tale. And we are about to start with the war cry sent out long ago by Hannibal, the great Carthaginian general:

«Soldiers [...] I implore you to make yourselves once more worthy of the reputation you trail after you; and remember the battle of Cannae!»

[In the original Latin text: «Miles [...] obtestor, dignos iam vosmet reddite vestra quam trahitis fama et revocate in pectore Cannas»].

Such are the words reported to us by Silius Italicus, a Roman consul and poet, who wrote his “Punica” at the end of the first century. In his work, Silius describes the anguish and sense of powerlessness that seized Hannibal's heart after the victorious battle of Cannae, followed by a long, idle stay of his army in the Campanian town of Capua. Hannibal fails in capitalizing on his winning moves against the Romans, as his soldiers lose their strength amid banquets and pleasures.

In this occurrence, Hannibal is led by local aristocrats into a visit of the surrounding region, which contains many wonders and notable places, most of them connected to the volcanic nature of the area. The Carthaginian general is shown Baiae, a fashionable resort lying by the Tyrrhenian sea, and the Lake Lucrinus, also known under the name of 'Cocytus' (just like the river flowing in the Otherworld of ancient Greece), and then Lake Avernus, or 'Styx' (another Greek river of the underworld), and the nearby swamps, loaded with dark legends connected to the realm of deads.

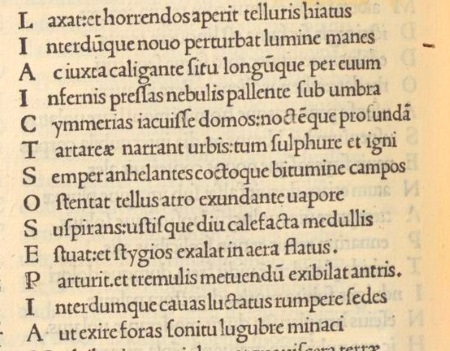

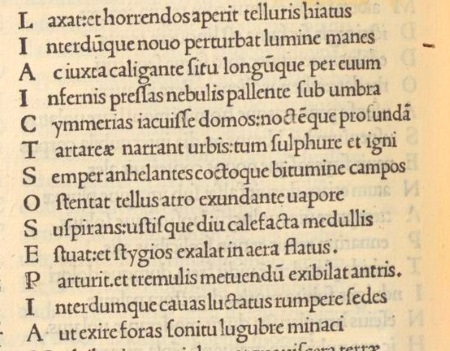

Finally, Hannibal listens to the following words (“Punica”, Chapter XII, v. 130-133, as they appear in an antique 1483 edition printed in Venice):

«Close at hand, wrapped in gloom and sunk for long ages in subterranean mists, the city of the Cimmerians lay deep in earth under a pall of shade; and tales are told about the unfathomed night of that Tartarean city».

[In the original Latin text: «Ac iuxta caligante situ longumque per aevum infernis pressas nebulis pallente sub umbra Cymmerias iacuisse domos noctemque profundam Tartareae narrant urbis»].

The subterranean houses of the Cimmerians. A place of mystery and darkness, which lay in the vicinity of Lake Lucrinus, Lake Avernus, and Baiae.

That is, near Cumae.

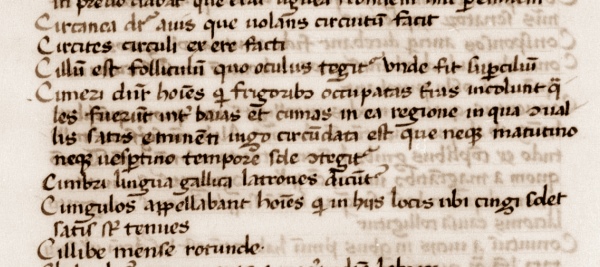

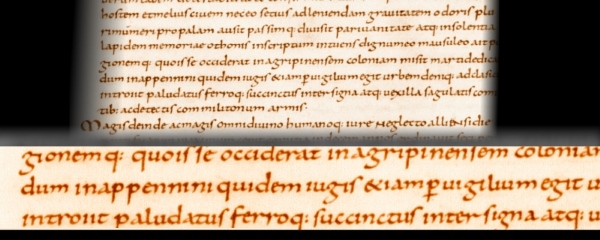

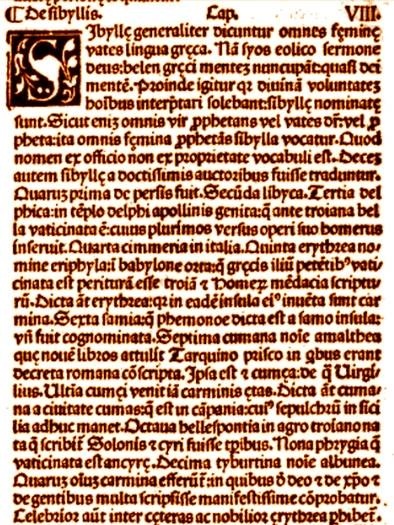

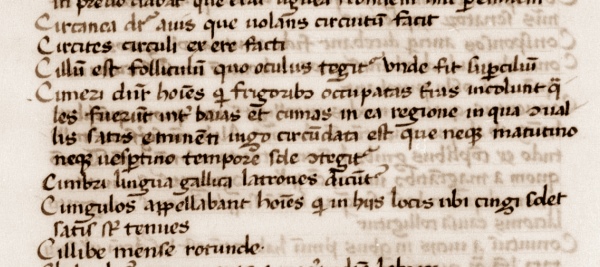

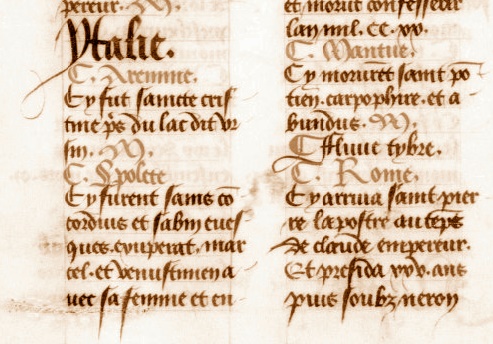

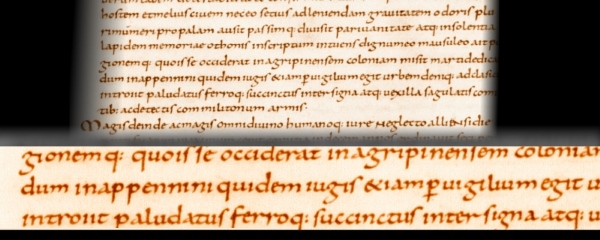

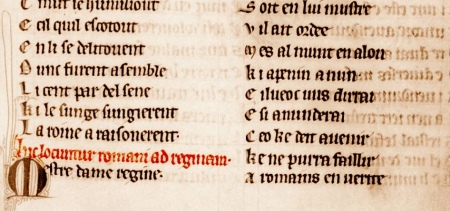

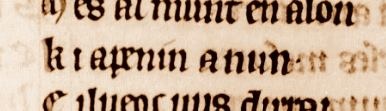

The Cimmerians are no Celts. In antiquity, it was in the region of Cumae that was located the Cimmerian town, a place of gloominess and absence of light. Here is how Sextus Pompeius Festus - a second-century writer who wrote a “De Verborum Significatione” (“On the meaning of words”), subsequently integrated by the benedictine monk Paul the Deacon - portrays the mysterious Cimmerians (Fig. 3 - Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Latin 7662):

«The Cimmerians are a population inhabiting lands which are subject to the cold of death, and lie between Baiae and Cumae, in the region where a low, large valley is encircled by a huge ridge; the place is never reached by the sun, neither in the morning nor in the evening».

[In the original Latin text: «Cimeri dicuntur homines, qui frigoribus occupatas terras incolunt, quales fuerunt inter Baias et Cumas in ea regione, in qua convallis satis eminenti iugo circumdata est, quae neque matutino, neque vespertino tempore sole contingitur»].

There is no surviving doubt: Herodotus' Cimmerians might have actually lived in the Caucasus, but they are different 'Cimmerians'. There existed, in ancient Italy, an Italic population that was based in the Campania province, in a region where the land itself was enshrouded in magic, which originated from the volcanic nature of the soil. And many authors report about them.

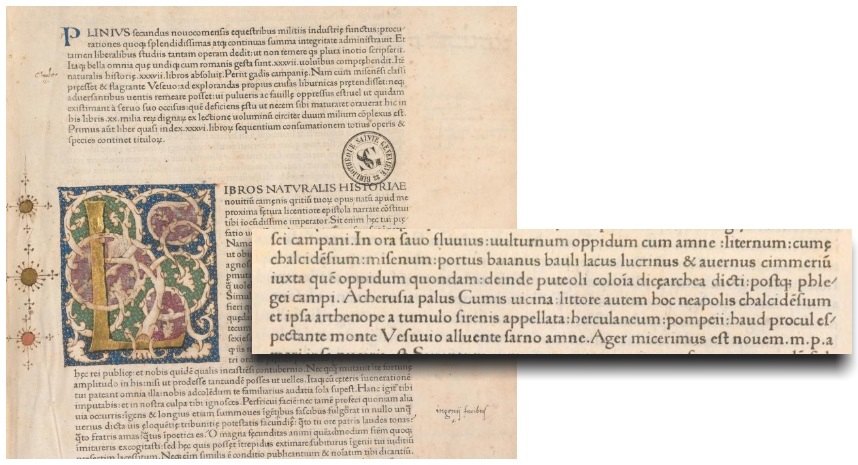

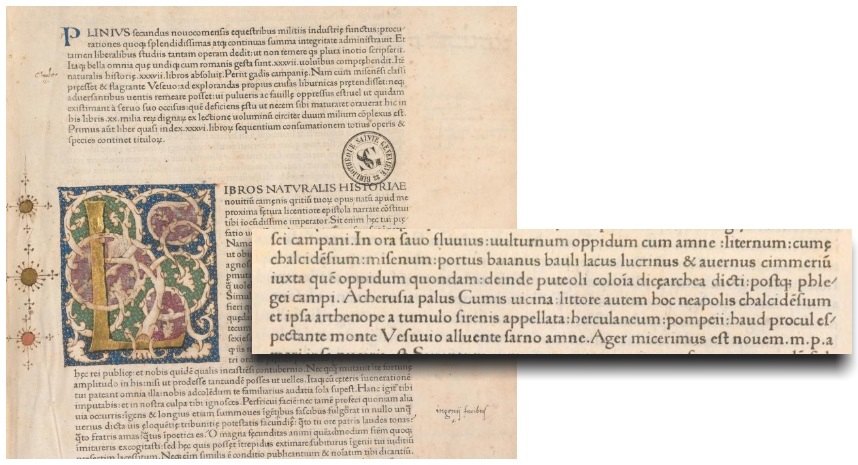

Pliny the Elder, in his first-century “Naturalis Historia”, says in Book III (Fig. 4) that «on the coast [we find] Cumae, a Chalcidian colony, Misenum, the port of Baiae, Bacoli, Lake Lucrinus and Lake Avernus, which is near to where once stood the Cimmerian town. We then come to Puteoli, formerly called the colony of Dicaearchia, then the Phlegraean Plains, and the Marsh of Acherusia in the vicinity of Cumae [...] and then Erculaneum, Pompeii...».

[In the original Latin text: «in ora [...] cumae chalcidesium, misenum, portus baianus, bauli, lacus lucrinus et avernus cimmerium iuxta quem oppidum quondam; deinde puteoli colonia dicerachea dicti, postquem phlegei campi. Acherusia palus Cumis vicina [...] herculaneum, pompeii...»].

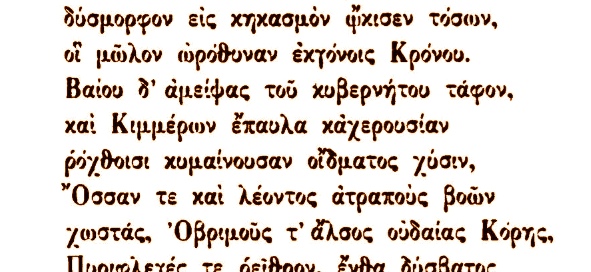

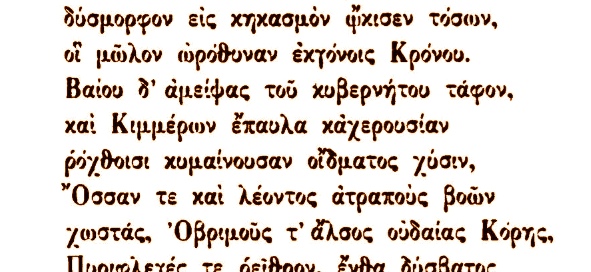

And in the third century, Lycophrone of Chalcis, in his poem “Alexandra” (v. 695 - Fig. 5), will write of Odysseus, who «pushes himself beyond the burial place of his helmsman Baius [modern Baiae] and the abode of Cimmerians and the Acherusian plain...», again locating the Cimmerians in the surroundings of Cumae.

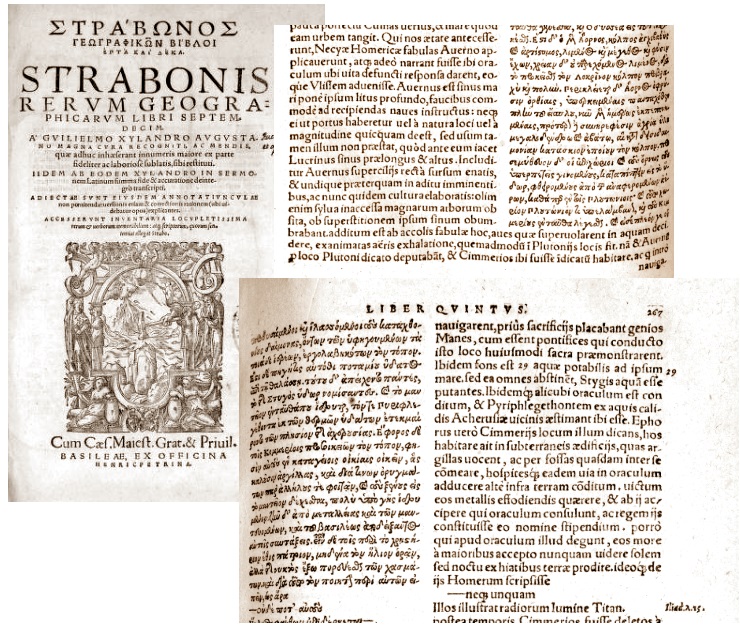

But it is Strabo, the Greek geographer and historian, who provides a most comprehensive reference about the Cimmerians in his most renowned “Geographica”, a work written in the first century. In Book V, he describes Cumae, Cape Miseno, the swamps called 'Acherontia' (another name for a river flowing in the Otherworld of ancient Greece), Baiae, the Lake Lucrinus, and the shadowy, blood-curdling Lake Avernus (Fig. 6):

«Avernus, entirely encircled by ridges above, looming on it from every side but a single point; it is now cultivated, however in old times it was enshrouded by an inaccessible wood made of huge trees, which covered with gloomy, superstitious shade the whole lake».

[In a 1571 Latin translation of the original text in Greek: «Avernus superciliis recta sursum enatis et undique praterquam in aditu imminentibus, ac nunc quidem cultura elaboratis; olim enim sylva inaccessa magnarum arborum obsita, ob superstitionem ipsum sinum obumbrabant»].

There, according to Strabo, was the abode of Cimmerians, and their oracle:

«People considered Avernum as a place sacred to Pluto, and that Cimmerians lived there [...] Ephorus maintained that this site was of the Cimmerians, about whom he says that they dwell in underground premises, which they call 'clay-made'; and they come to and fro through subterranean tunnels, and by the same way they allow visitors to the oracle which is deeply dug into the ground; they live on the metal ore they mine, and on those who consult the oracle. [...] And in addition to that, there is an ancient custom that those who live by the oracle must never see the sun, as they can only go outside through the crevices in the ground when the night comes».

[In the Latin translation: «Nam et Avernum p loco Plutoni dicato deputabat, et Cimmerios ibi fuisse indicatu habitare [...] Ephorus vero Cimmeriis locum illum dicans, hos abitare ait in subterraneis aedificiis, quas argillas vocent, ac per fossas quasdam inter se comeare, hospitesque eadem via in oraculum adducere alte infra terram conditum, victum eos metallis effodiendis quarere, et ab ii accipere qui oraculum consulunt [...]. Porro qui apud oraculum illud degunt, eos more a maioribus accepto nunquam videre solem sed noctu ex hiatibus terrae prodire»].

We are getting closer and closer to the true origin of the Cimmerian Sibyl. We have come to Cumae and by the shore of Lake Avernus, in the Italian region of Campania. And we know that the mysterious, almost mythical Cimmerians lived in underground dwellings, and controlled an oracle, deeply set in a subterranean shrine.

Was that oracle a Sibyl?

Yes it was. It was a Cimmerian Sibyl. As we will discover in the next article.

Una Sibilla chiamata Cimmeria: un'investigazione sulla possibile relazione con la Sibilla Appenninica - 6. L'oracolo dei Cimmeri

Ci troviamo ancora sulle tracce della Sibilla Cimmeria, il quarto oracolo menzionato nella classica lista delineata da Lucio Cecilio Firmiano Lattanzio nel quarto secolo. Una Sibilla che, in alcune versioni delle "De Divinis Institutionibus" di Lattanzio viene indicata come "Cumea", un appellativo che riporta alla mente del lettore la parola 'Cuma', la città della Campania nella quale profetava la Sibilla Cumana, la quale, a propria volta, è presente nella lista di Lattanzio con il numero sette.

Ma dove si troverebbe la Sibilla Cimmeria? Secondo Francesco Maurolico, autore siciliano del sedicesimo secolo, essa sarebbe originaria di una città chiamata «Ameria», oppure di un villaggio il cui nome è «Cimerio», situato in prossimità delle grotte di Norcia, in modo tale da far corrispondere la Sibilla Cimmeria con la Sibilla Appenninica, che dunque non sarebbero altro che il medesimo oracolo.

Eppure, a sostenere questa identità è solamente Maurolico (e Padre Fortunato Ciucci da Norcia, che nel diciassettesimo secolo, citerà brani tratti da Maurolico).

Nessun altro autore od opera riferisce di una simile identificazione, né le fonti primarie di Maurolico (il "Mappemonde Spirituelle" di Jean Germain, che abbiamo avuto occasione di considerare in un precedente articolo), né altre fonti quali gli "Oracula Sibyllina" o gli "Opuscula" di Filippo Barbieri.

Se vogliamo arrivare alla verità, non abbiamo allora altra scelta: dobbiamo volgerci verso il passato e tornare agli autori della classicità.

La chiave di tutto questo problema si trova nella vera natura e identità del popolo conosciuto con il nome di 'Cimmèri'. Oggi, molti sono convinti che i Cimmèri siano stati un'antica popolazione tribale vissuta nella regione del Caucaso. In effetti, il loro nome è mezionato dallo storico greco Erodoto, ed essi sono inoltre divenuti parte di una più diffusa cultura popolare contemporanea grazie ai racconti fantasy di Conan il Cimmero, ideati dal narratore americano Robert E. Howard, in cui i Cimmèri sono rappresentati come appartenenti ad una cultura di origine celtica e nordeuropea.

Ma si tratta solamente di una tradizione secondaria, benché certamente la più nota tra il grande pubblico, riguardante il popolo dei Cimmeri.

Perché se andiamo a ricercare i Cimmèri nella letteratura della classicità, non troviamo né Celti né tantomeno il Caucaso: ci troviamo, invece, ad essere riportati verso un luogo che già conosciamo. E lo conosciamo bene, grazie ad una famosa, notissima Sibilla.

E questo luogo è Cuma.