8 Dec 2017

Domenico Falzetti: a life for music, a life for the Sibyl /2

«One day, it happened some sixty years ago - so a boy began to speak to his young friends - a man came to Norcia, looking for brave, ruthless companions; he was a Frenchman and he was determined to go as far as the Sibyl's cave, in a hunt for legendary treasures. He said he had a map with him, depicting the internal arrangement of the Sibyl's hollows, he stated he fully knew the secrets concealed within that drawing, as he knew how to read it and how to spot the exact point where the treasure was hidden».

This is the opening of an account set down by Domenico Falzetti, a typewritten document now at the Norcia Municipal Library. It is a tale that cast a spell on Falzetti when he was a child, and urged the man to dedicate his whole life to the enchanting mystery of the Apennine Sibyl.

«Following a few days of feverish arrangements, the treasure hunters set out from Norcia in the dead of night», writes Falzetti. And it seems to us to read anew the brave deeds accomplished by Guerrino the Wretch, the knight who faced the unknown, his heart full of hope and courage as he started his journey to the mountains. «After many hours of exhausting walk they attained the mountain-top», adds Falzetti. However, for the dauntless adventurers hardships weren't over yet. Actually they had just begun.

«The entranceway [to the cave] was exceedingly obstructed, more than they had expected. To clear it up they would spend time and a lot of demanding work. [...] After a quick look at the situation, they thought they would rather drill a new passageway». The tale is set at the mid of the nineteenth century and the cave, as we already know, was sealed and inaccessible since many centuries earlier.

However, our heroes do not give up. They clear from rocks and rubble a second pathway to the cave, so that at last they can «creep into a void and reach the cavern's inner part»: a dream comes true, that had been housed in the hearts of innumerable travellers for centuries and centuries. It is the start of a quest, a magical route into gloom and darkness, bringing them right into the secret places hidden in the unfathomable depths of the cave.

«They secured themselves with ropes and their exploration began. The ground on which they treaded was not firm; their feet seemed to sink into it. They had to be careful and restrain the excitement they had felt following their lucky start».

A feeling of uneasy apprehension began to beset the minds of the adventurers, now fully treading the soil of the forbidden kingdom of Queen Sibyl: «the passageway ahead was a bit too narrow. The light, remarkably faint, suggested to us that we should fire up a torch. That reddish flame, smoky and utterly unstable (the flame of an old-fashioned link), cast on the cave's walls sinister, eerie shadows».

The main characters of our tale are now ready to meet the weird, the inexplicable, the uncanny. The cavern itself appeared to be bound in an unnatural, wicked spell: «they summoned all their courage and the pick hit the ground again and again. It looked like brushing away the sand from the seafloor!», writes Falzetti. Now the very leader of the party seemed to be overwhelmed by the evil fascination oozing from the cave: «meanwhile the Frenchman intently scrutinized all things around him: with increasing apprehension he looked at the men working, now with frantic efforts».

Then, something happened.

«Suddenly a terrified scream resounded in the cavern... A huge snake had popped up between the Frenchman's feet and then vanished with a hiss».

How to forget Guerrino the Wretch and his encounter with Macho the Snake, at the entrance of the Sibyl's cave, «a big-sized reptile twenty-four feet long which seemed to be made of earth, bulky at mid-length and definitely ugly»?

Now the time, for the once-dauntless treasure hunters, begins to run quick. «Fear started to pervade our hearts. The desire to leave that gloomy place became unbearable. The Frenchman proposed to recover their wits in the open air, out from that cavern».

But a last encounter awaited them: emerging from the very darkness of the cave, «they saw a weird animal, with the likeness of a toad, its eyes glowing like embers [...] and fiercely staring at them...».

They feared it might be the Fiend in person, and «all fled the best they could». Insanity seemed to take hold of their souls, because when they found themselves «outside the cavern they were enveloped in a thick fog. Their failing minds saw Our Lady who pointed her finger towards the path to their salvation».

The Sibyl had called their name, and then had repelled them, just like the countless visitors - real men and literary characters - that had been so bold as to climb that mount throughout the centuries.

And don't you assume that such things never happen in our present time: during a presentation session I held last summer ("Sibyl - A Secret of Stone"), I collected the words of an attendee who told me that he had once been caught by fog and storm on the Sibyl's mountain-top, amid flashing lightnings which were furiously striking the precipitous peak; and that he had found his way down thanks to an indistinct shadow who, among the frenzied clouds, appeared to point her finger to the way he had to go for safety. That was but a tree - he told me - but how to keep from thinking that up there, where no trees grow at all, a benevolent entity might have helped him toward his own salvation, as he himself thought it had actually happened?

Such are the tales that nourish the antique legend of the Apennine Sibyl. A tale, like the one reported by Domenico Falzetti, «of the kind which lives forever in the soul of children. Yet it did not convey dread to my heart, on the contrary it fostered in me a yearning to go and visit that mysterious cave».

A long search, a lifelong one, had just started in the soul of Falzetti: a quest devoted to the ancient myth of a Sibyl. A legendary tale that still casts spells on the minds of today's men.

[Falzetti's tale, as contained in a typewritten document registered under no. 11366 at the Norcia Municipal Library, is reported in the most fascinating book "The Last Sibyl (L'Ultima Sibilla)'" by Maria Luciana Buseghin, Carsa Edizioni, Pescara, 2012]

Domenico Falzetti: una vita per la musica, una vita per la Sibilla /2

«Un giorno, circa sessant'anni fa - così prese a dire un giovane ad altri suoi coetanei - giunse a Norcia, in cerca di uomini coraggiosi e senza scrupoli, un francese, diretto alla Grotta della Sibilla, per ritrovarvi favolosi tesori. Egli diceva di possedere un disegno (pianta) particolareggiato dell'interno della grotta sibillina, affermava di conoscere i segreti di quel disegno e di sapervi leggere e precisare il punto dove poteva essere nascosto il tesoro».

Così comincia il racconto di Domenico Falzetti, custodito in un dattiloscritto conservato presso la Biblioteca Comunale di Norcia. È il racconto che avrebbe affascinato Falzetti bambino, e che lo avebbe spinto a dedicare la propria vita al magico enigma della Sibilla Appenninica.

«Dopo qualche giorno di intensa preparazione, i cercatori di tesori partirono da Norcia nel cuore della notte», scrive Falzetti. E sembra di rileggere le ardite avventure di Guerrin Meschino, il cavaliere che affronta l'ignoto con cuore impavido e pieno di speranza, mentre comincia il suo viaggio verso le montagne. «Giunsero alla meta dopo varie ore di cammino estenuante», scrive ancora Falzetti. Ma le prove, per quei cercatori di tesori senza paura, sono solo all'inizio.

«L'entrata [della grotta n.d.r.] era eccessivamente ostruita, più di quanto avessero supposto. Per sgombrarla occorreva lungo tempo e faticoso lavoro. [...] Dopo un rapido esame, stimarono più opportuno praticare una nuova entrata». Siamo intorno alla metà del diciannovesimo secolo e la caverna, come noto, è già occlusa ed impenetrabile da molti secoli.

Ma i nostri eroi non si perdono d'animo. Dopo avere liberato dai massi una seconda via, essi finalmente «poterono penetrare in un vuoto all'interno della grotta», realizzando così il sogno che aveva occupato per secoli e secoli i cuori di innumerevoli viaggiatori. Comincia così un viaggio iniziatico, un percorso magico nel buio e nell'oscurità, che li porterà verso i luoghi segreti nascosti all'interno della grotta.

«Legatisi con corde iniziarono l'esplorazione. Il terreno su cui camminavano non era compatto; i piedi vi si affondavano. Occorreva estrema prudenza e mitigare l'entusiasmo suscitato dal felice inizio».

Una sensazione di sottile inquietudine comincia a diffondersi nelle menti di quegli avventurieri, ormai penetrati nel regno proibito della Regina Sibilla: «Più avanti, il passaggio era un po' troppo angusto. La luce piuttosto scarsa consigliò di accendere una torcia. Quella luce rossastra, fumiginosa e continuamente instabile (luce di torcia a vento), proiettò sulle pareti ombre strane e indefinibili».

I protagonisti di questa storia sono ormai pronti per l'incontro con l'arcano, con l'inspiegabile, con il sovrannaturale. La stessa grotta sembra essere avvolta da un incantesimo strano e ostile: «ripreso coraggio, il piccone tornò ad affondarsi nella terra. Sembrava come rimuovere la rena del mare!», scrive Falzetti. Anche il capo degli avventurieri sembrava ora subìre il fascino oscuro, maligno della grotta: «il francese intanto consultava ogni cosa all'intorno: con ansia seguiva il lavoro fattosi febbrile».

Qualcosa, infatti, accade.

«Ad un tratto un grido di spavento risuonò nella grotta... Fra i piedi del francese era passato improvviso un grosso serpente ed era fuggito sibilando».

Come non pensare al Guerrin Meschino e al suo incontro con il serpente Macho, all'ingresso della grotta della Sibilla, «uno grande serpente longo circa quatro braza e pareva proprio de terra grosso in lo mezo e molto era bruto»?

Ma ormai il tempo, per quelli che erano stati in principio ardimentosi cercatori di tesori, comincia a correre veloce. «La paura cominciò a far capolino. Il desiderio di fuggire da quel luogo divenne prepotente. Il francese suggerì di ritemprare lo spirito all'aria libera, fuori dalla caverna».

Un ultimo incontro però li attende: dal profondo della grotta «videro comparire un animale dalle forme strane, un poco simile a un rospo, dagli occhi di brace [...] i suoi occhi sfavillavano, guardavano terribili...».

Temendo che si trattasse del demonio in persona, «ciascuno fuggì come poté». La pazzia sembrò impossessarsi delle loro menti, perché quando furono «fuori dalla caverna una fitta nebbia li avvolse. La loro mente ormai malata vide la Madonna che additava loro premurosa la via della salvezza».

La Sibilla li aveva chiamati, e li aveva respinti, come gli innumerevoli visitatori reali e letterari che hanno osato, nei secoli ascendere, quella montagna.

E non crediate che ciò non accada ancora oggi: durante una delle mie presentazioni estive dal titolo “Sibilla - Il Segreto di Pietra”, ho potuto raccogliere le parole emozionate di una persona, la quale mi raccontava di essere stato sorpreso dalla nebbia e dalla tempesta sulla cima della Sibilla, tra fulmini che trafiggevano irati il picco scosceso, e di avere trovato la via per discendere grazie a un'ombra indistinta che, tra le nubi impazzite, sembrava indicargli la strada. Non era che un albero, mi disse, ma come non pensare che lassù, dove gli alberi non vivono affatto, una qualche potenza benigna non possa avergli indicato il sentiero verso la salvezza, come egli stesso affermava di ritenere?

Sono questi i racconti che alimentano il mito secolare della Sibilla Appenninica. Racconti, come quello di Domenico Falzetti, «che rimangono nella memoria dei fanciulli. Ma anziché paura mi generò il desiderio di conoscere da vicino un così misteriosa grotta».

Sarebbe cominciata così la ricerca, lunga una vita, di quel musicista, alla scoperta del mito antico della Sibilla. Un mito che sorprende e affascina ancora oggi.

[il testo di Falzetti, contenuto nel dattiloscritto coll. 11366 conservato presso la Biblioteca Comunale di Norcia, è tratto dal bellissimo ed informatissimo volume “L'Ultima Sibilla” di Maria Luciana Buseghin, Carsa Edizioni, Pescara, 2012]

5 Dec 2017

Domenico Falzetti: a life for music, a life for the Sibyl /1

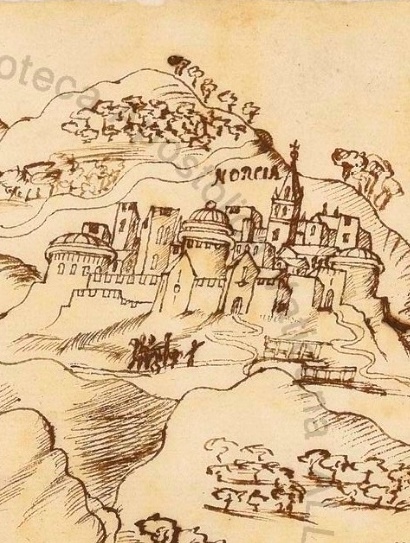

Domenico Falzetti, a name which is almost forgotten today. Yet in the 1950s he was a celebrated musician, the conductor in Italy of a famous "The One-Thousand-Little-Singer Choir" set up by the Centre for Artistic Education (CEA), an organization established after World War II by Guido Mestica, a superintendent of the public school system in Rome, to promote the love for arts and music among the youngsters. With his one-thousand children, Falzetti used to travel all around Italy featuring his young choir members in theaters at all main Italian towns (in the picture, a rare frame of Falzetti in his conduction role and a commemorative medal with his name inscribed on it).

That was an intense passion for music which has never deserted Falzetti's soul. He was married to the celebrated soprano Maria Viscardi, a famous singer who was born in Rieti, and the queen of opera houses all around the globe throughout the first quarter of the twentieth century.

However, conductor and musician Domenico Falzetti housed in his heart another ardent passion as well: that for the legend of the Apennine Sibyl.

Born in Norcia on April, 11th 1896, throughout his life he had been bewitched by the fairy tale of the crowned mountain and its inaccessible cavern. «A mysterious fascination», as his daughter Julia wrote, «an appeal which I have never fully understood nor examined urged my father, Domenico Falzetti, to 'climb the lofty peak of Mount Sibyl more than once' and turn that mount, and the legends which have made it so widely known, into the main object of his work, and entire life».

Falzetti will ascend the cliff of that mountain, up to its secretive cave, on many fundamental occurrences: the first time in 1920, when he established in Montemonaco an historical "Committee for the excavation of Mount Sibyl's cavern" together with Mario Monti Guarnieri; again in 1925, when the excavations will uncover «a sort of lintel carved in stone, with squared edges», an unmistakable sign of the fact a man's hand had been working on that natural hollow; and once again the following year, in 1926, with the aid and support of the Department of Antiquities and Heritage in the provinces of Marche and Abruzzi, the public office which accepted to be involved in the expedition by the urge of an illustrious philologist, Pio Rajna, a Senator of the Kingdom of Italy; again in August 1930, with the company of another philologist from Belgium, Fernand Desonay, when they thought they could feel «a faint whiff of air» coming out from the abyss underneath; and finally in 1953, when a fully equipped expedition unearthed «beneath the rubble a Tournois coin of Henry II, a spur and a knife».

But the Sibyl's spell, with the enchanted magic of her call, had striken Domenico Falzetti's soul ever since a long-gone past. At that time, he had not yet climbed the mysterious, crowned mountain.

«Possibly I was just out of my earlier youth when I heard for the first time, in Norcia, just by chance, the following tale which produced a vivid impression on my heart...»

We will see that this tale, to which a child named Falzetti had listened with wide-open eyes, was not so dissimilar from the amazing accounts that Andrea da Barberino had set down in his romance "Guerrino the Wretch", nor any different from the legendary narratives reported to Antoine de La Sale by the peasants who accompanyed him up to the Sibyl's peak on May, 18th 1420.

Now let's listen to the evocative, beguiling tale that Domenico Falzetti heard in Norcia when he was but a small child.

Domenico Falzetti: una vita per la musica, una vita per la Sibilla /1

Domenico Falzetti, una figura oggi quasi del tutto dimenticata. Eppure, negli anni 1950 egli fu un famoso musicista, direttore del notissimo “Coro dei Mille Piccoli Cantori” del CEA - Centro di Educazione Artistica, un'istituzione voluta, negli anni del dopoguerra, da Guido Mestica, Provveditore agli Studi di Roma, per promuovere tra le giovanissime generazioni l'interesse verso la musica e le arti. Con quei mille bambini, Falzetti viaggiava per tutta l'Italia, esibendo i piccoli coristi nei teatri delle principali città (nella foto, una rara immagine di Falzetti e del suo coro, con una medaglia commemorativa che riporta il suo nome).

Un amore, quello per la musica, che non avrebbe mai abbandonato il Falzetti, sposato con il celebre soprano di origine reatina Maria Viscardi, regina dei teatri lirici di tutto il mondo nel primo quarto del ventesimo secolo.

Ma il musicista Domenico Falzetti albergava nell'animo anche un altro, differente amore: quello, bruciante, per la leggenda della Sibilla Appenninica.

Nato a Norcia l'11 aprile 1896, per tutta la vita egli fu ammaliato dal mito della montagna coronata e della sua inaccessibile grotta. «Un fascino misterioso», scriverà la figlia Giulia, «un'attrazione che non ho mai troppo capito o analizzato spinse mio padre, Domenico Falzetti, a salire “ripetutamente sulla impervia vetta del Monte Sibilla” e fare di quel monte e delle leggende, che lo hanno reso famoso, il fine principale del suo lavoro, e della sua vita».

Falzetti si recherà sulla vetta di quella montagna, fino alla misteriosa grotta, in varie occasioni fondamentali: la prima volta, nel 1920, quando, con Mario Monti Guarnieri, fonderà a Montemonaco uno storico “Comitato per gli scavi nella grotta del Monte Sibilla”; ancora, nel 1925, quando gli scavi porteranno alla luce «una specie di architrave di pietra sagomata e squadrata», segno sicuro che la mano dell'uomo aveva contribuito a modificare sensibilmente quella cavità naturale; e, nuovamente, l'anno successivo, nel 1926, con il supporto della Soprintendenza alle Antichità delle Marche e degli Abruzzi, l'istituzione che fu possibile coinvolgere grazie all'intervento e alla sollecitazione dello stimato filologo Pio Rajna, Senatore del Regno; ancora nell'agosto del 1930, assieme al filologo belga Fernand Desonay, quando si credette di poter percepire, proveniente dal fondo dell'abisso, «una leggera corrente d'aria»; e infine nel 1953, quando una ben equipaggiata spedizione riuscirà a scoprire «sotto i crolli, [...] un soldo tornese di Enrico II, uno sperone e un coltello».

Ma il fascino della Sibilla, con il magico incantesimo del suo richiamo, aveva colpito Domenico Falzetti già da molto tempo. Ben prima che egli salisse, per la prima volta, sulla misteriosa montagna coronata.

«Potevo essere uscito dalla fanciullezza quando per la prima volta udii, a Norcia, così a caso, questo racconto che allora mi impressionò vivamente...»

Vedremo come questo racconto, ascoltato da un Falzetti bambino, gli occhi sgranati dalla meraviglia, non fosse poi così diverso dalle favolose narrazioni che Andrea da Barberino aveva riportato nel suo romanzo “Guerrin Meschino”, né differente dalle fantastiche storie riferite ad Antoine de La Sale dai popolani che lo avevano accompagnato sulla cima della Sibilla il 18 maggio del 1420.

Ma ascoltiamo anche noi il racconto, suggestivo e affascinante, udito da Domenico Falzetti, a Norcia, quando ancora era solo un bambino.

21 Sep 2017

Norcia, 1703: a description of the earthquake by Fr. Antonio d'Orvieto /2

In his “Chronicles of the Province of the Friars Minor of Umbria, or Assisi”, Fr. Antonio d'Orvieto continues his account of 1703 earthquake in Norcia by reporting the first anticipatory signs of the destruction-to-come:

«To begin my most distinguished tale in an orderly fashion, first I will tell you, through the accounts of thoroughly reliable People, who had the unhappy chance to behold the ghastly occurrence, that on October, 18th 1702, a day dedicated to St. John the Evangelist, at 13 in the morning, the ground was shaked by a seismic wave which was so long and terrible that it produced tangible damages [...] Then other quakes followed, but they were less strong, until January, 14th 1703; and they were a matter for concern among Residents, though no further damages were added. [...] Yet penances and offerings proved to be insufficient to allay God's inflamed Wrath».

Then, it all happened:

«On January, 14th 1703, [...] a Sunday, [...] at 1:45 in the night so fierce and migthy an earthquake came, subsequently followed by many others which were not less frightful throughout the whole extent of that mournful night, and accompanied by thunders and bolts and rains and gloomy darkness and sulphurous smell and bitumen stench and uninterrupted quivers of the ground, that in addition to the complete slaughter of Norcia it appeared the quake was determined to swallow everything it found above the ground, with the upheaval and sinking of all buildings, and their displacement first to one side and then to the other. To all that it must be added the loud noise of the town's collapsing walls, the high cries, the dreadful uproar and the calling voices from the underground».

As in a movie's sequence, Antonio d'Orvieto provides a number of visions of that ghastly night (we spare the reader Antonio's horrifying descriptions of people under the ruins - they are too ghastly even for our contemporary taste):

«Everybody was terrified, and scared by the darkness of the night, and by the unrelenting quivering of the earth [...] St. Benedict [...] whose church suffered great damage, and owing to the collapse of the falling stones the vaulted ceiling of the lower Church, where the Magnificent Brother Saints Benedict and Scholastica were born, opened up, and even its lavish Belfry was harmed, though not thoroughly, as its four huge bells got loose from their support and stood still, incredibly enough, amid the high arches of the belfry without falling down despite the many frightful blows of the Earthquake. The Main Collegiate Church was totally ruined [...] with the utter collapse of its nice Belfry, recently built. As to the second Collegiate Church, said of St. John, half of it went down, and the remaining half appeared to be scattered with appalling cracks. [...] The Apostolic Palace, called the Small Castle, [...] well reinforced with its sloping walls, resisted all shocks, mighty as they were, with only a few cracks popping up in its Vaulted Rooms».

Thus, what we find in this description is that in year 1703, in Norcia, a ruin occurred which is not dissimilar from that experienced in 2016: today we actually see the same churches badly damaged or collapsed.

However, a difference can be outstandingly spotted: in 1703, says Antonio d'Orvieto, «Norcia had reduced itself to a broken pile of wooden beams, a heap of rubble, and a ruin of stones»; by contrast, today's downtown Norcia has basically resisted, with a far stronger resilience than three centuries ago. Roofs and walls still stand in place, owing to an improved strengthening of the buildings achieved in the last decades. That's why Norcia will soon enjoy a new start up and development phase - as it already did after 1703 - but at a much quicker pace than after the terrible earthquakes occurred in the eighteenth century.

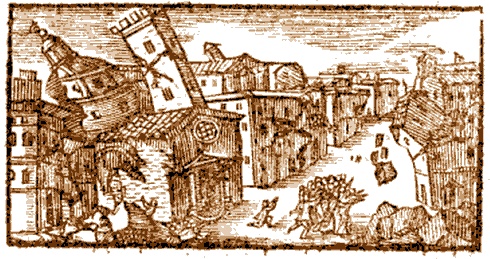

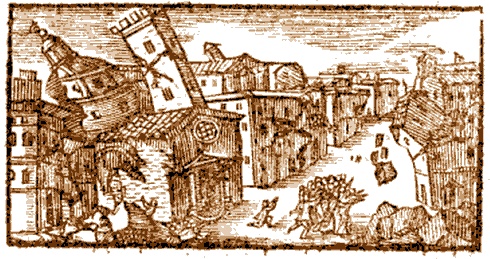

[In the picture: a drawing of a ruined town contained in the “Historical account of the Earthquakes perceived in Rome, and in portions of the Papal States and other places in the evening of January, 14th [...]” published in Rome by Lucantonio Chracas in 1704]

Norcia, 1703: una descrizione del terremoto redatta da Padre Antonio d'Orvieto /2

Nella sua "Cronologia della Provincia Serafica Riformata dell'Umbria o d'Assisi", Padre Antonio d'Orvieto prosegue con il suo racconto relativo al terremoto del 1703 a Norcia, narrandoci delle prime avvisaglie che sembrarono far presagire la successiva distruzione:

«E per dar principio con qualche ordine al mio più distinto racconto, dirovvi primieramente col testimonio di Persone molto degne di fede, e che furono con sua gran pena presenti al tremendissimo spettacolo, Come alli 18 d'Ottobre del 1702, giorno dedicato all'Evangelista S. Luca, verso le 13 ore della mattina diede la terra in una scossa così lunga, e terribile, che cagionò sensibil danno [...] Seguitarono poi a farsi sentire i terremoti più leggiermente fino alli 14 di Gennaio, e contuttoché tenessero in qualche apprensione gli Abitatori, non cagionarono però altro danno. [...] ma non furono a bastanza le penitenze, ed i Sagrifizj per placare l'Ira accesa Divina».

Poi, tutto ebbe luogo:

«Alli 14 dunque di Gennajo dell'anno 1703, [...] caduto in quell'anno di Domenica, [...] ad un'ora, e quasi tre quarti di notte del detto giorno venne un così fiero e terribile Terremoto, seguitato da molti altri di non minore spavento in tutto lo spazio di quella funestissima notte, ed accompagnato da' tuoni, da' lampi, da' piogge, da' oscurità tenebrose, da' puzze solfuree, da' fetori bituminosi, e da così continoui tremori della terra, che oltre l'intero eccidio di Norcia, sembrava che assorbir volesse quanto le stava di sopra, or' alzandosi, or' abbassandosi quasi tutte le fabbriche, e quando agitavansi da una banda, e quando dall'altra; al che si aggiugnevano lo strepitoso fragore delle mura, che rovesciavano, strida spaventose, clamori terribili, e voci sotterranee».

Come in una sequenza cinematografica, Antonio d'Orvieto ci presenta una serie di immagini che ci riportano a quella terribile notte (risparmiamo al lettore alcune impressionanti descrizioni, riportate da Padre Antonio, concernenti persone sepolte dalle rovine - particolarmente crude anche per la nostra moderna sensibilità):

«Tutti [erano] atterriti dallo spavento, e spaventati dall'oscurità della notte, e dall'incessante traballar della terra [...] S. Benedetto [...] la cui chiesa sofferse un grave danno, ed al cadere de' materiali aprissi la volta della Chiesa di sotto, dove nacquero i Gloriosi Santi Germani Benedetto, e Scolastica, il cui sontuoso Campanile restò offeso, benché non molto sensibilmente, schiodandosi da' loro sesti le sue quattro grosse Campane, che tutte rimasero con grande stupore su gli archi de' loro stessi fenestroni senza mai cadere a basso a tante orribili scosse de' Terremoto. La Chiesa Collegiata Matrice restò del tutto rovinata [...] rovesciando anche interamente il suo bel Campanile di poco tempo compiuto. Della seconda Collegiata, detta di S. Giovanni, se ne atterrò la metà, e nel rimanente fu piena di spaventose fessure. [...] Il Palazzo Apostolico, detto la Castellina, [...] ben fortificato dalle sue forti mura a scarpa non cadde a tante scosse, benché terribili di quei Terremoti, se non che comparve qualche apertura nelle Volte delle sue Stanze».

Dunque, ciò che possiamo rilevare in questa descrizione è che nell'anno 1703 si verificò, a Norcia, una rovina non molto dissimile rispetto a quella occorsa nel 2016: oggi, infatti, possiamo vedere che ad essere gravemente danneggiate o del tutto crollate sono proprio le medesime chiese.

C'è una differenza, però, che sembra delinearsi con grande risalto: nel 1703, racconta Antonio d'Orvieto, la città andò soggetta ad una totale distruzione, «essendosi ridotta Norcia quasi tutta ad un mucchio di confusi legnami, ad un cumulo di calcinacci, e ad una maceria di sassi». Al contrario, oggi la Norcia storica ha sostanzialmente resistito, dimostrando una resilienza ben superiore rispetto a tre secoli orsono. Tetti e mura sono ancora in piedi, grazie all'accresciuta resistenza degli edifici implementata negli scorsi decenni. Ecco perché Norcia potrà presto ripartire ed entrare in una nuova fase di sviluppo, come già in effetti fece anche dopo il 1703, ma lo farà ad un passo drasticamente più veloce rispetto a quanto avvenne a valle dei terribili terremoti del diciottesimo secolo.

[Nell'immagine: una città distrutta dal terremoto rappresentata nel "Racconto istorico de Terremoti Sentiti in Roma, e in parte dello Stato Ecclesiastico e in altri luoghi la sera de' 14 di gennaio [...]" di Lucantonio Chracas, 1704]

18 Sep 2017

Norcia, 1703: a description of the earthquake by Fr. Antonio d'Orvieto /1

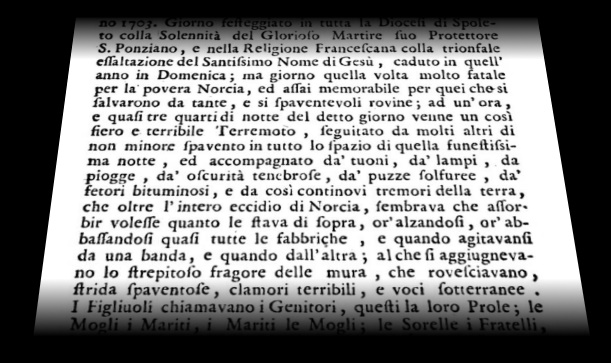

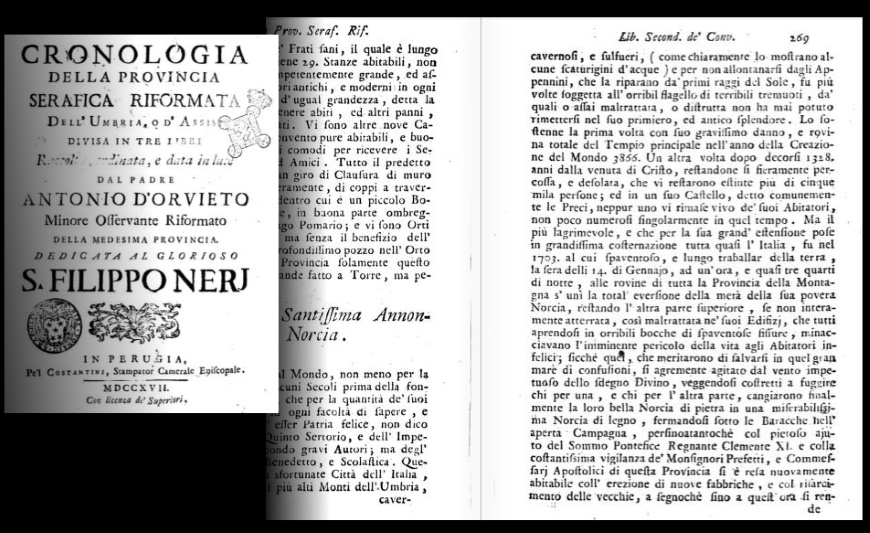

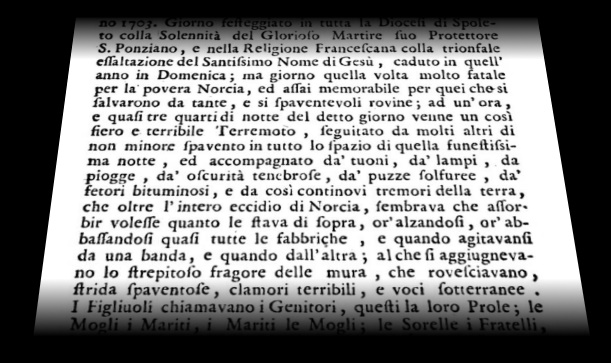

One of the most remarkable events in the history of Norcia is certainly the great earthquake of 1703. And one of the most striking, impressive accounts of those events of centuries ago is contained in the “Chronicles of the Province of the Friars Minor of Umbria, or Assisi”, written by Fr. Antonio d'Orvieto in 1717.

«Norcia, a most illustrious town in the world», writes Antonio d'Orvieto, «[..] more than once was hit by the awful curse of mighty earthquakes, which either injured or ruined it so much that it could never restore itself in its previous magnificence. [...] However, the most grievous event, which by his extent greatly upset the largest portion of Italy, took place in 1703, when in the occurrence of a frightful, long-lasting shaking of the ground on the evening of January, 14th, at 1:45 in the night, the wreck of the whole Province of the Mountain came together with the utter destruction of half of wretched Norcia, leaving the remaining upper portion - if not entirely razed to the ground - so ruined in its Buildings that all of them showed awful voids made of appalling cracks, and they endangered right away the lives of its poor inhabitants; so that those who deserved salvation in that large sea of chaos, bitterly swept by the contempt of God, seeing they were forced to flee some here and some else there, transformed their charming Norcia, originally made of stone, into a wholly miserable, wooden Norcia, as they looked for shelter under shacks in the open countryside [...]».

This is the beginning of the vivid account written by Fr. Antonio d'Orvieto on the formidable earthquake that struck Norcia in 1703. Yet, the Franciscan friar, who writes his report a few years only after the ruinous event, also offers to our modern view a vision of new hope and achieved reconstruction:

«[...] until, with the merciful support by the Ruling Sublime Pontiff, Clement XI, and with the uninterrupted supervision by the Monsignor Chief Magistrates and the Apostolic Delegates of this Province, Norcia was rendered a habitable town again by raising new buildings and through the restoration of the old ones; and so much so that Norcia is presently even handsomer than before in her newly-constructed buildings and in the renovation of her beautiful Churches in a likewise modern form».

Thus Norcia has always re-built itself after each earthquake, even the most appalling one. A lesson that must be always kept in mind when discouragement seems to be in command of the hearts of people.

In the next post, we will see how Antonio d'Orvieto continues his chronicle, providing a pictorial description of the seismic events with utter fervency and emotional involvement, bringing us right in the middle of the town's past history.

[in the picture: a drawing of the ruined town of L'Aquila in 1703 contained in a “Report on the damages caused by the floods and earthquake in the town of L'Aquila, And in other sites nearby” published in Rome the same year]

Norcia, 1703: una descrizione del terremoto redatta da Padre Antonio d'Orvieto /1

Uno degli avvenimenti più importanti nella storia di Norcia è stato certamente il grande terremoto del 1703. E una delle descrizioni più intense e toccanti di quegli eventi del passato è contenuta nella "Cronologia della Provincia Serafica Riformata dell'Umbria o d'Assisi", scritta da Padre Antonio d'Orvieto nel 1717.

«Norcia, chiarissima nel Mondo, [...] fu più volte soggetta all'orribil flagello di terribili tremuoti, da' quali o assai maltrattata, o distrutta non ha mai potuto rimettersi nel suo primiero, ed antico splendore. [...] Ma il più lagrimevole, e che per la sua grand'estensione pose in grandissima consternazione tutta quasi l'Italia, fu nel 1703, al cui spaventoso, e lungo traballar della terra la sera delli 14 di Gennajo, ad un'ora, e quasi tre quarti di notte, alle rovine di tutta la Provincia della Montagna s'unì la total eversione della metà della sua povera Norcia, restando l'altra parte superiore, se non interamente atterrata, così maltrattata ne' suoi Edifizj, che tutti aprendosi in orribili bocche di spaventose fissure, minacciavano l'imminente pericolo della vita degli Abitatori infelici; sicché quei, che meritarono di salvarsi in quel gran mare di confusioni, si agremente agitato dal vento impetuoso dello sdegno Divino, veggendosi costretti a fuggire chi per una, e chi per l'altra parte, cangiarono finalmente la loro bella Norcia di pietra in una miserabilissima Norcia di legno, fermandosi sotto le Baracche nell'aperta Campagna».

Così comincia il vivido racconto redatto da Padre Antonio d'Orvieto sul terribile sisma che colpì Norcia nel 1703. Eppure, il padre francescano, il quale scrive solamente a pochi anni di distanza dal disastroso evento, offre alla nostra visione di contemporanei immagini di nuova speranza e di ricostruzione positivamente avvenuta:

«[...] perfinoatantoché col pietoso ajuto del Sommo Pontefice Regnante Clemente XI e colla costantissima vigilanza de' Monsignori Prefetti, e Commessarj Apostolici di questa Provincia si è resa nuovamente abitabile coll'erezione di nuove fabbriche, e col risarcimento delle vecchie, a segnoché fino a quest'ora si rende assai più vagha di prima negli edifizj singolarmente moderni, e nella rinuovazione parimente moderna delle sue belle Chiese».

Nel prossimo post, vedremo come Antonio d'Orvieto prosegua la sua cronaca, fornendoci una descrizione per immagini di quel terremoto, con grande drammaticità ed intensa partecipazione emotiva, riportandoci nel pieno degli eventi storici di allora.

[nell'immagine: una rappresentazione delle rovine della città dell'Aquila nel 1703 contenuta in una “Relazione de' danni fatti dall'innondazioni e terremoto nella città dell'Aquila, Ed in altri luoghi Circonvicini”, pubblicata in Roma nello stesso anno]

15 Sep 2017

The fame of ancient Norcia: truffles, cured pork meat and the Sibyl /2

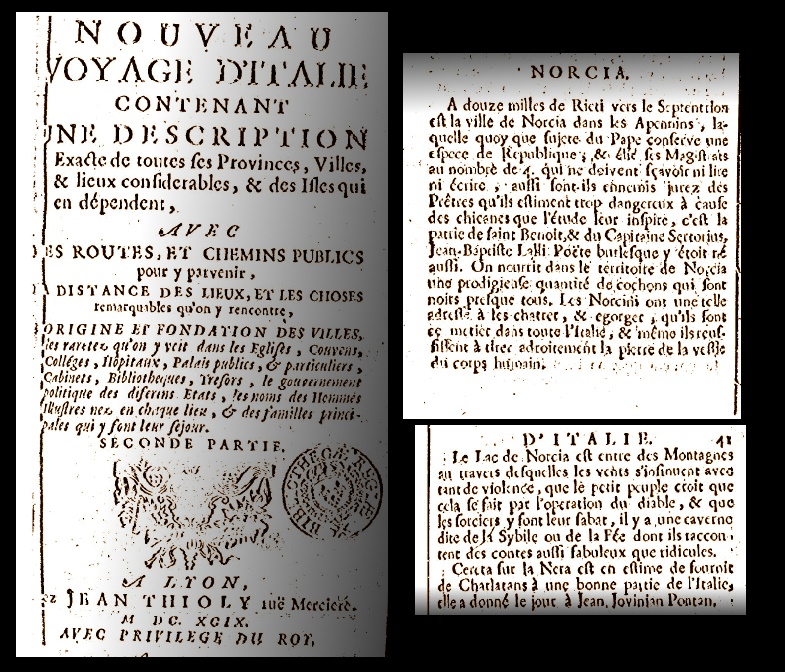

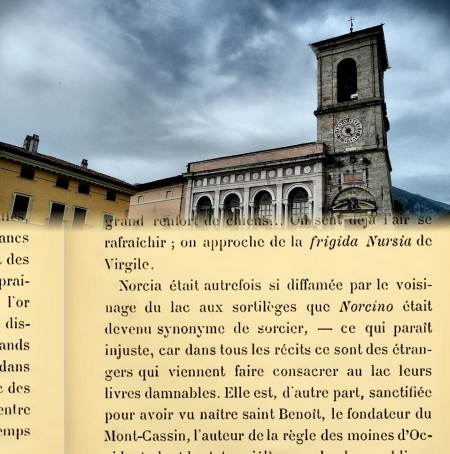

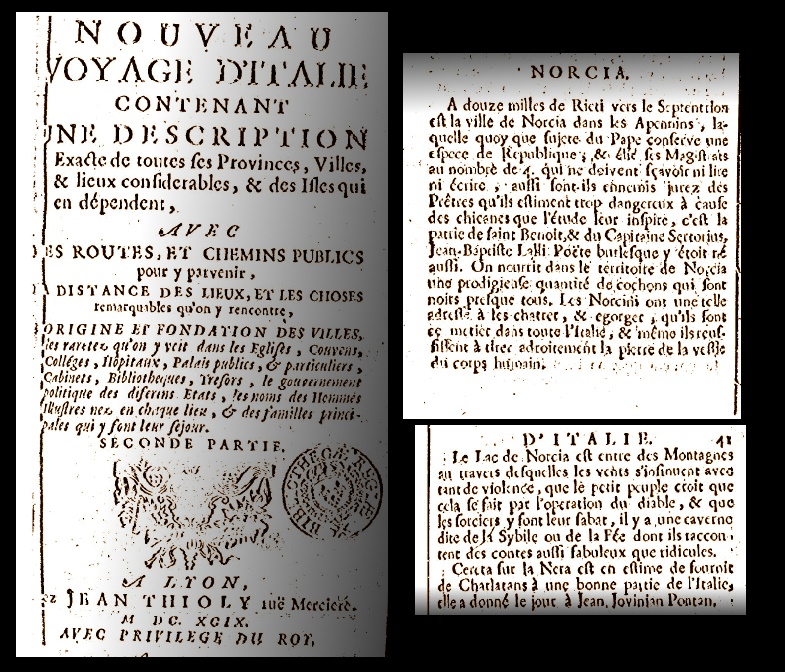

Another instance of the renown of Norcia in past centuries can be retrieved in François-Jacques Deseine's “A new journey to Italy” (“Nouveau voyage d'Italie”) published in 1699. In this book we find the complete list of Norcia's most famed peculiarities: from the odd rumor about the illiteracy of his rulers (we dedicated a specific post to this topic) to the art of butchery in Norcia and, finally, to the magical lakes and caverns lying in its territory:

«Twelve miles north of Rieti is the town of Norcia set amid the Apennines; despite its being under Papal rule it retains a sort of Republican status. The town chooses its four rulers, who must be ignorant of reading and writing; the inhabitants are also foes of the Priests, who are reputed exceedingly dangerous owing to the tricks that their education suggests to them. Norcia is the hometown of St. Benedict and Commander Sertorius. Giovanni Battista Lalli, a burlesque poet, was born in the town as well».

After the above introduction, Deseine starts praising the art of Norcia's butchers:

«In the territory of Norcia, a huge number of swines are bred, most of them with black skin. The people from Norcia are so adept at castrating and slaughtering them that they practice this art all around Italy. They are also proficient in removing stones from the human bladder».

And finally, the magical side:

«The Lake of Norcia stands between Mountains through which the winds creep so fiercely that the common people believes this happens under the urge of the fiend, and sorcerers use to hold their Sabbath there; there is also a cavern said of the Sibyl or the Fairy, of which they tell tales as whimsical as risible».

This is Norcia's complex, layered cultural heritage: for sure, not many such small places in the world can claim so manifold local traditions. A wealth that should be exploited to lure tourists into this tiny, wondrous town.

[in the original French text: «A douze milles de Rieti vers le Septentrion est la ville de Norcia dans les Apennins, laquelle quoy que sujete du Pape conserve une espece de Republique, et élit ses Magistrats au nombre de 4, qui ne doivent savoir ni lire ni écrire, aussi sont-ils ennemis jurez des Prêtres qu'ils estiment trop dangereux à cause des chicanes que l'étude leur inspire, c'est la patrie de saint Benoit & du Capitaine Sertorius, Jean-Baptiste Lalli poëte burlesque y étoit né aussi. On nourrit dans le territoire de Norcia une prodigieuse quantité de cochons qui sont noirs presque tous. Les Norcini ont une telle adresse à les chatrer, & egorger, qu'ils font ce metier dans toute l'Italie, & même ils reussissent à tirer adroitement la pierre de la vessie du corps humain. Le Lac de Norcia est entre des Montagnes au travers desquelles les vents s'insinouent avec tant de violence, que le petit peuple croit que cela se fait par l'operation du diable, & que les sorciers y font leur sabat, il y a une caverne dite de la Sybile ou de la Fée dont ils raccontent des contes aussi fabuleux que ridicules.»]

La fama dell'antica Norcia: tartufi, norcineria e Sibilla /2

Un altro esempio della fama di Norcia nei secoli passati può essere reperito nel volume di François-Jacques Deseine "Nouveau voyage d'Italie", pubblicato nel 1699. In esso troviamo un elenco completo di tutte le più famose peculiarità nursine: dalla strana dicerìa a proposito dei suoi illetterati governanti (abbiamo dedicato un post specifico a questo particolare tema), all'arte della norcineria, fino ai magici laghi e caverne presenti nel suo territorio:

«A dodici miglia da Rieti verso Settentrione si trova la città di Norcia, tra gli Appennini; questa città, benché soggetta al Papa, si comporta come una sorta di Repubblica, ed elegge i propri Magistrati in numero di quattro, i quali non devono sapere né leggere, né scrivere; inoltre, gli abitanti di Norcia sono nemici giurati dei Preti, che essi reputano troppo pericolosi a causa delle malizie che lo studio ispira loro. È la patria di San Benedetto & del Capitano Sertorio; Giovanni Battista Lalli, poeta burlesco, vi è nato anch'egli».

Dopo questa introduzione, Deseine inizia a magnificare l'arte della norcineria:

«Nel territorio di Norcia si alleva una prodigiosa quantità di maiali, che sono quasi tutti neri. I Norcini hanno una tale abilità nel castrarli e macellarli che essi praticano questo mestiere in tutta Italia, & essi riescono anche ad estrarre la pietra dalla vescica del corpo umano».

E, infine, gli aspetti magici:

«Il Lago di Norcia si trova tra Montagne attraverso le quali i venti si insinuano con tanta violenza, che il popolino crede che ciò avvenga per opera del demonio, & che i maghi vi tengano i loro sabba. C'è anche una caverna detta della Sibilla o della Fata della quale essi raccontano storie tanto favolose quanto ridicole».

Questa è la complessa, stratificata eredità culturale di Norcia: di certo, non molti luoghi nel mondo, così piccoli e quasi sperduti, sono in grado di vantare tradizioni locali così varie e differenziate. Una ricchezza che andrebbe sviluppata per attrarre ulteriore turismo verso questa piccola, mirabile città.

[nel testo originale francese: «A douze milles de Rieti vers le Septentrion est la ville de Norcia dans les Apennins, laquelle quoy que sujete du Pape conserve une espece de Republique, et élit ses Magistrats au nombre de 4, qui ne doivent savoir ni lire ni écrire, aussi sont-ils ennemis jurez des Prêtres qu'ils estiment trop dangereux à cause des chicanes que l'étude leur inspire, c'est la patrie de saint Benoit & du Capitaine Sertorius, Jean-Baptiste Lalli poëte burlesque y étoit né aussi. On nourrit dans le territoire de Norcia une prodigieuse quantité de cochons qui sont noirs presque tous. Les Norcini ont une telle adresse à les chatrer, & egorger, qu'ils font ce metier dans toute l'Italie, & même ils reussissent à tirer adroitement la pierre de la vessie du corps humain. Le Lac de Norcia est entre des Montagnes au travers desquelles les vents s'insinouent avec tant de violence, que le petit peuple croit que cela se fait par l'operation du diable, & que les sorciers y font leur sabat, il y a une caverne dite de la Sybile ou de la Fée dont ils raccontent des contes aussi fabuleux que ridicules.»]

13 Sep 2017

The fame of ancient Norcia: truffles, cured pork meat and the Sibyl /1

As shown in previous posts, Norcia was once known throughout Europe as a land of magic: a territory to which foreign people came to ascend Mount Sibyl and visit the Lake of Pilatus.

However, Norcia was also well known for the very same reasons that make up the fame of the place in our present days: truffles (how delicious!) and cured pork meat (the renowned, tasty 'norcineria').

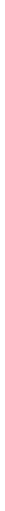

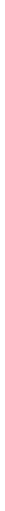

In a 1747 edition of Franz Schott's “Itinerary through Italy”, a travel guide originally intended for Jubilee pilgrims, Norcia is described as a town «twelve miles north of Rieti, set amid the Apennines, and subject to the Holy See, yet enjoying substantial freedom. This town (despite its unealthy climate, and prone to earthquakes, by which the land has been almost completely ruined in recent years) is praised for having been the birthplace of a famed Sertorius, who was defeated by Gnaeus Pompeius, and of St. Benedict as well, the Patriarch of the Monastic Order in western Europe».

And, then, a description of Norcia's most renowned arts of that time follows. «Those people have great skills as it comes to castrating and removing kidney stones; they practice their art on swines that suffer from the same sickness, of which animals a great quantity is found; they even use them to unearth truffles, as many of them can be found in the countryside. In this land are still present a few honorable families, as the Passarini, the Senzasono, ond others».

Today just like centuries ago: Norcia is still renowned for its magical, toothsome food.

[in the picture: eleventh-century fresco depicting the ancient art of butchery on the right wall of the Church of St. Maria Immacolata in Ceri (RM)]

La fama dell'antica Norcia: tartufi, norcineria e Sibilla /1

Come illustrato in precedenti post, Norcia era un tempo conosciuta in tutta Europa come luogo di magia: una terra verso la quale gente straniera si recava per ascendere il Monte Sibilla e visitare il Lago di Pilato.

Ma non è tutto. Norcia era anche molto nota per la stessa identica ragione che rende questi luoghi così rinomati anche ai nostri giorni: il tartufo (una meravigliosa bontà!) e la lavorazione delle carni suine (la famosa, saporitissima 'norcineria').

In una edizione del 1747 dell'"Itinerario d'Italia" di Franz Schott, una guida di viaggio originariamente pensata per i pellegrini dei Giubilei, Norcia è descritta come una città «dodici miglia da questa Città [Rieti] lontano verso settentrione, [...] situata negl'Appennini, sottoposta alla Sede Apostolica, che gode degl'ampli privilegj. Si vanta questo luogo (non però di buon'aria, e sottoposto a i Terremoti, da' quali in quest'ultimi anni è stato quasi affatto rovinato) di avere dato i natali al famoso Sertorio, vinto da Pompeo, ed a S. Benedetto Patriarca dell'Ordine Monastico in Occidente».

Poi, ecco una descrizione delle più famose arti nursine del tempo. «Sono questi popoli naturalmente pratici di castrare, e cavar pietre; esercitandosi negl'animali porcini, sottoposti a simili mali, de' quali ve ne è gran quantità, che anche gli servono a discoprire i tartufi, che ve ne sono molti nella campagna. Vi è ancora in questo luogo qualche buona Famiglia, come i Passarini, Senzasono, ed altre».

Oggi come tanti secoli fa: Norcia è ancora famosa ed apprezzata per le sue magiche, gustosissime specialità culinarie.

[nell'immagine: affresco dell'XI sec. raffigurante l'antica arte della norcineria posto sulla parete destra della Chiesa di S. Maria Immacolata a Ceri (RM)]

23 Aug 2017

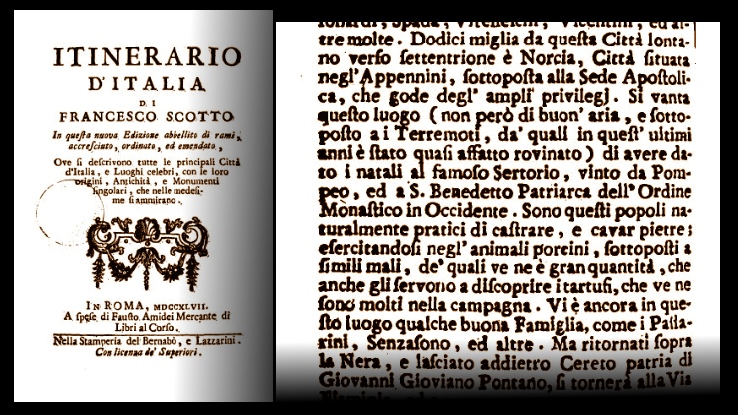

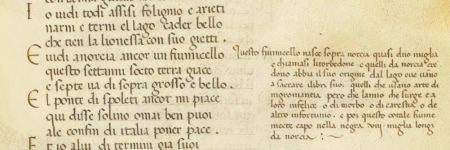

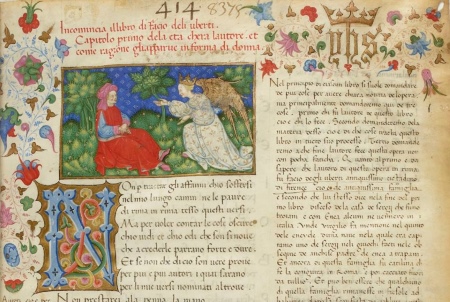

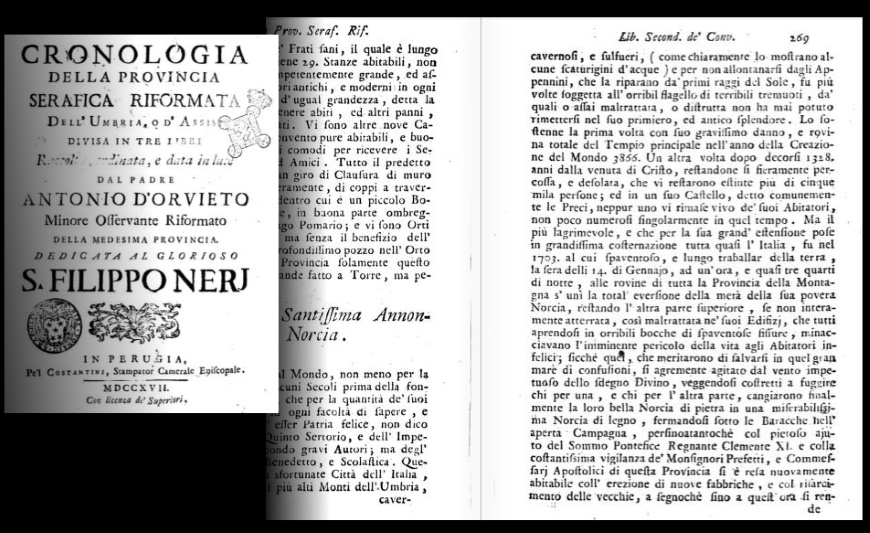

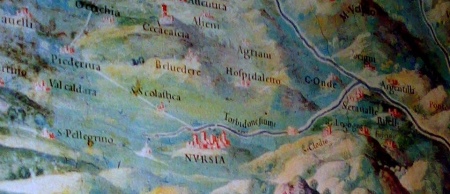

The Apennine Sibyl in a sixteenth-century vatican manuscript: the fabled domes of Norcia

In previous posts we presented a Vatican manuscript (Vat Lat 5241) depicting a sixteenth-century journey to Mount Sibyl, possibly drawn by Baldo Angelo Abbati or his fellow-scholar and most famous printer and publisher Aldo Manuzio the Younger.

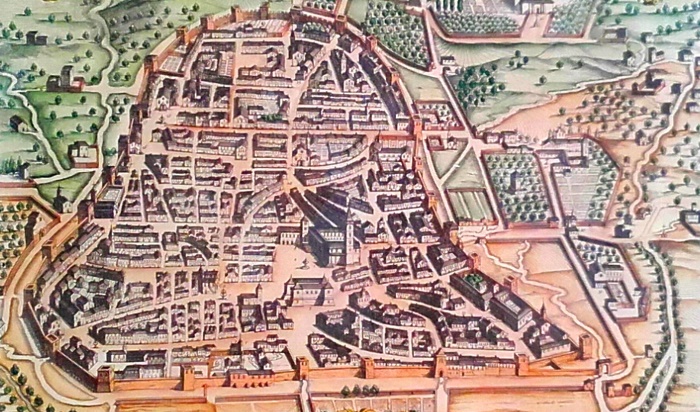

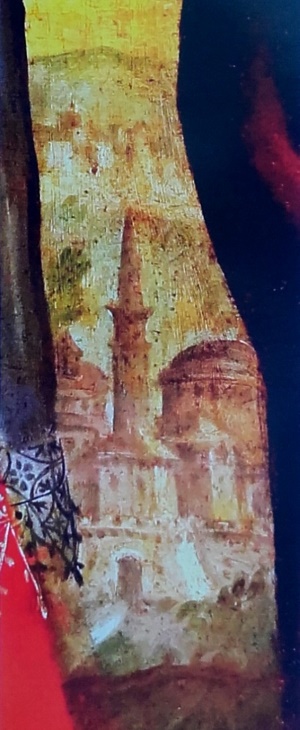

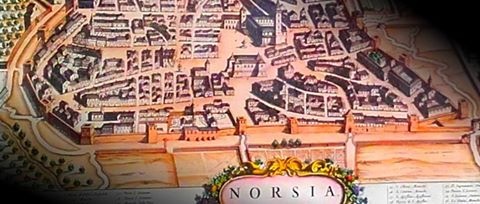

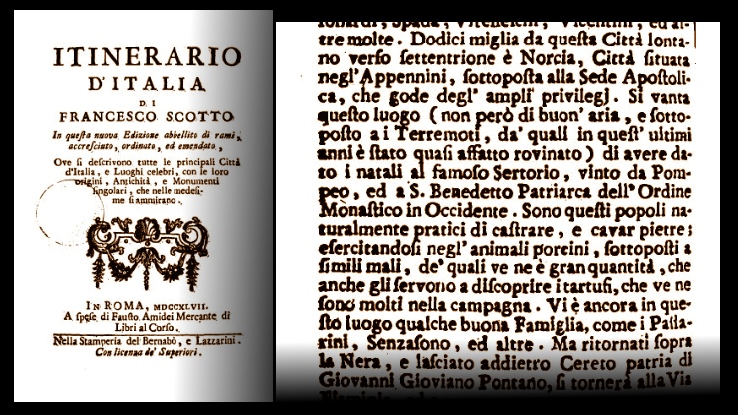

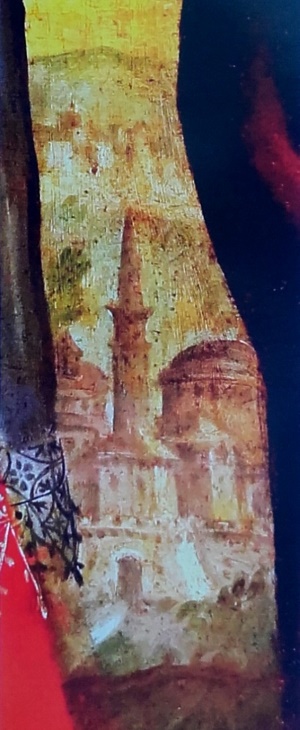

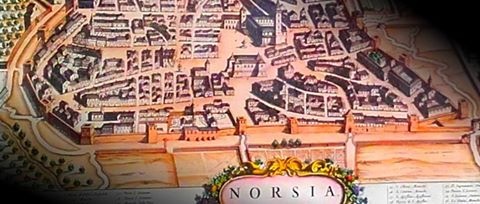

Surprisingly enough, in the manuscript Norcia is portrayed as a rich, walled city, with towers and domed churches (see figure 1). The surprising feature is connected to the presence of domes, which are missing altogether in both present and historical Norcia.

Did the manuscript's draftsman actually ever visit Norcia? Is the manuscript a true, reliable information source?

The answer is yes. And let's check out why.

Before the destructive earthquake that struck the town in 1703, Norcia really HAD domes, though singular as it may seem today.

Look at this seventeenth-century fresco which was painted in Norcia's Basilica of St. Benedict at the altar of St. Lucy (now unfortunately heavily damaged after the collapse of the Basilica on October, 30th 2016): as noted by historian Romano Cordella, the Basilica itself was adorned with domes, and more than one (see figure 2). This is precisely the same vision provided to us in the drawing contained in Vat Lat 5241.

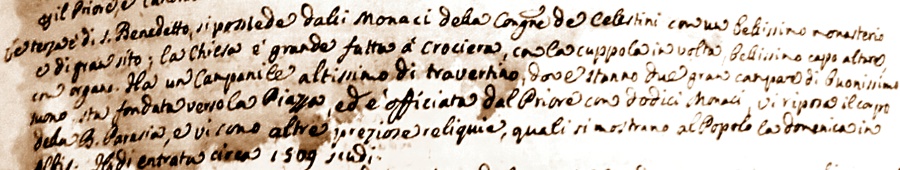

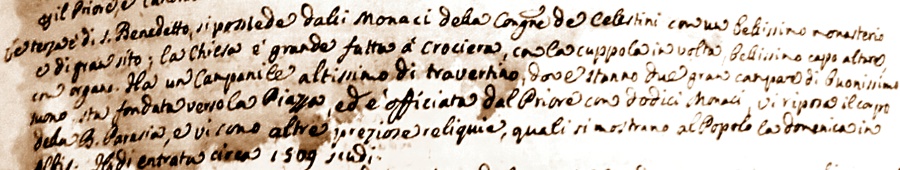

As an additional confirmation to the presence of domes in Norcia before 1703, Romano Cordella has retrieved an excerpt written by Giovanni Battista Lalli, a poet from Norcia who lived in the seventeenth century (see figure 3). Here is how the man of letter describes the Basilica at that time:

«The church of St. Benedict is ruled by the monks of the Order of the Celestinians with a most charming monastery of great size; the church is huge and cross-shaped, with a DOME above, a splendid main altar, with a pipe organ. It has a lofty belfry made of travertine stone, where two large bells provide the most charming chimes; it raises beside the main square and is run by the abbot and twelve monks...»

Thus, Vat Lat 5241 tells no lies. It is a true witness to the magical spell of the Apennine Sibyl's legend in the sixteenth century. A document that will need further study and insight.

[in the original Italian text: «La [chiesa?] di S. Benedetto si possiede dalli monaci della Congregazione de' Celestini con un bellissimo monasterio e di gran sito; la chiesa è grande, fatta a crociera, con la CUPPOLA in volta, bellissimo capo altare, con organo. Ha un campanile altissimo di travertino, dove stanno due grandi campane di buonissimo suono, sta fondata verso la piazza, ed è officiata dal priore con dodici monaci...»]

La Sibilla Appenninica in un manoscritto vaticano del sedicesimo secolo: le leggendarie cupole di Norcia

In precedenti post abbiamo presentato un manoscritto vaticano (Vat Lat 5241) il quale ci descrive una cinquecentesca escursione al Monte Sibilla, compiuta forse da Baldo Angelo Abbati o dal suo amico ed erudito, nonché famosissimo editore e stampatore, Aldo Manuzio il Giovane.

Nel manoscritto, Norcia è ritratta come una città ricca, cinta di mura e - sorprendentemente - popolata di cupole (vedere fig. 1). Questa inattesa caratteristica soprende l'osservatore, proprio perché né nella Norcia di oggi, né nella città del secolo scorso risultano essere presenti cupole di alcun genere.

Il dubbio che si presenta alla mente è, dunque, se l'autore del manoscritto abbia mai veramente visitato Norcia. È possibile considerare questo antico documento come una fonte di informazione veritiera ed affidabile?

La risposta è positiva. E vediamo insieme perché.

Prima del terribile terremoto che distrusse la città nel 1703, Norcia ERA realmente dotata di cupole, per quanto singolare oggi possa sembrare.

Osserviamo questo affresco seicentesco che era conservato all'interno della Basilica di San Benedetto a Norcia, presso l'altare di Santa Lucia (oggi purtroppo fortemente danneggiato dal crollo della Basilica avvenuto il 30 ottobre 2016): come notato dallo storico Romano Cordella, la Basilica stessa era coronata da cupole, e addirittura più di una (vedere fig. 2). Questa è esattamente la medesima immagine restituitaci nel disegno contenuto nel manoscritto Vat Lat 5241.

Come ulteriore conferma della presenza di cupole a Norcia prima del 1703, Romano Cordella ha reperito un brano scritto di pugno di Giovanni Battista Lalli, un poeta nursino vissuto nel diciassettesimo secolo (vedere fig. 3). Ed ecco come l'uomo di lettere descrive la Basilica del suo tempo:

«La [chiesa?] di S. Benedetto si possiede dalli monaci della Congregazione de' Celestini con un bellissimo monasterio e di gran sito; la chiesa è grande, fatta a crociera, con la CUPPOLA in volta, bellissimo capo altare, con organo. Ha un campanile altissimo di travertino, dove stanno due grandi campane di buonissimo suono, sta fondata verso la piazza, ed è officiata dal priore con dodici monaci...»

Quindi, il manoscritto Vat Lat 5241 non ci racconta falsità. Si tratta di una testimonianza affidabile relativa alla magica fascinazione connessa alla leggenda della Sibilla Appenninica nel sedicesimo secolo. Un documento che dovrà essere certamente oggetto di ulteriori studi e approfondimenti.

14 Aug 2017

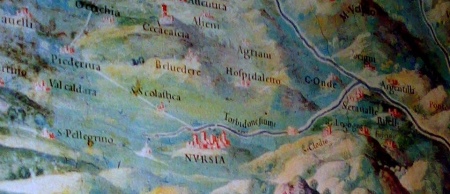

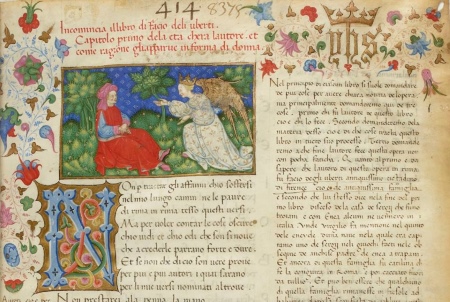

Torbidone, the river that resurfaces from the hidden core of the Sibillini Range

There is a river that has gained a widespread renown throughout the centuries: the Torbidone, a streamlet that flows in the territory of Norcia and whose peculiar behaviour has stricken the imagination of men of letters and scientists.

The Torbidone appears and then vanishes for years following the seismic activity that hits periodically the Sibillini Range region. After the 2016 earthquakes and a forty-year-long disappearance, it has resurfaced again, with a considerable flow rate as it drains waters that are normally hidden in titanic subterranean reservoirs concealed amid the perforated limestone which form the foundation of the Sibillini Mountain Range and its Castelluccio plateau.

From centuries, its resurfacing point lies - as is today - in a ploughed field sitting at the very base of a hill near the town of Norcia: the Colle Vallacone (or Vallaccone - see images 1 and 2), where the gently sloping ground turns suddently into a marsh of mud and wet herbage, as the waters start to spring up from different spots in the field.

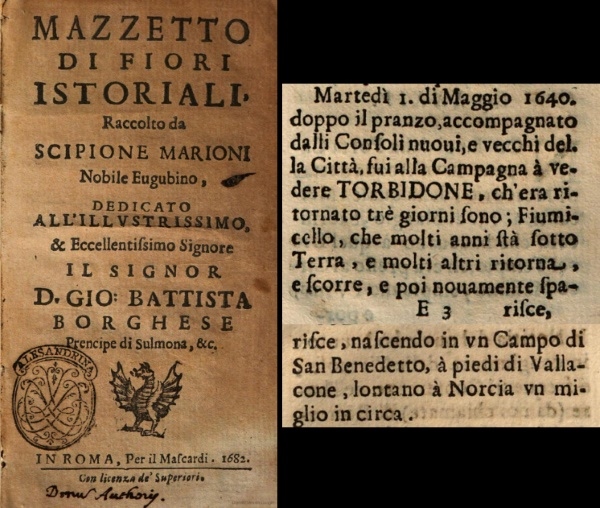

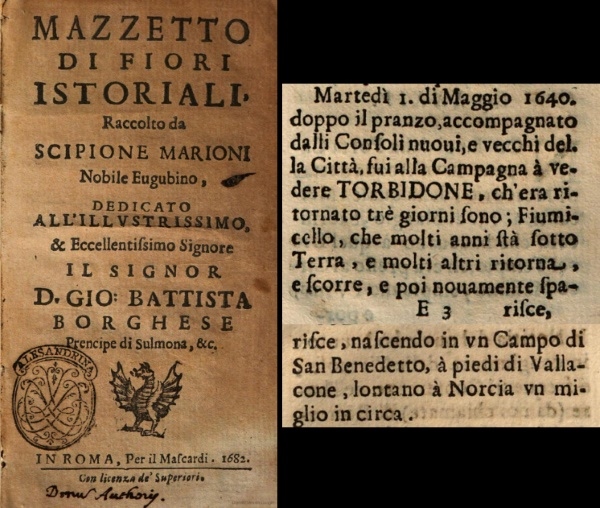

Many ancient literary excerpts can be retrieved on this prodigious creek (the most famous is to be found in fourteenth-century “Dittamondo” by Fazio degli Uberti). One of them is drawn from the book “A collection of historical flowers” published in 1682 by Scipione Marioni, a nobleman and scholar from Gubbio, who reports the words written by Monsignor Lodovico della Valle, Chief Magistrate of Norcia and the surrounding mountainous region (image 3). The Prefect had the chance to visit the springs on Tuesday, May 1st 1640:

«After lunch, accompanyied by the present and past Consuls of the town, I went to the countryside to see the Torbidone, which had just resurfaced three days before; it's a small river that runs beneath the ground for many years, and subsequently it reappears and flows openly, then it vanishes again. It pops up in a field of Saint Benedict, at the foot of Vallacone, a mile away from Norcia».

Just as more than three hundred years ago, the Torbidone now runs across the countryside again (image 4): an apparently mirthful, harmless token of the immense, frightening might of earthquakes.

Torbidone, il fiume che riemerge dalle profondità nascoste dei Monti Sibillini

C'è un fiume che si è conquistato una vasta fama attraverso i secoli: il Torbidone, un piccolo corso d'acqua che scorre nel territorio di Norcia, ed il cui peculiare comportamento ha colpito nel tempo l'immaginazione di scienziati e uomini di lettere.

Il Torbidone appare e in seguito scompare per lunghi anni, in stretta correlazione con l'attività sismica che periodicamente colpisce la regione dei Monti Sibillini. Dopo i terremoti del 2016 e un'assenza durata circa quaranta anni, il fiume è ricomparso nuovamente, con una portata considerevole, derivante dal drenaggio delle acque che sono normalmente nascoste nei titanici serbatoi sotterranei sepolti al di sotto del calcare carsico che costituisce le fondamenta dei Monti Sibillini e dell'altipiano di Castelluccio.

Per secoli, il punto di risorgenza del Torbidone si è palesato - così come anche oggi - all'interno di un campo coltivato posto proprio alla base di una collina nelle vicinanze della città di Norcia: il Colle Vallacone (o Vallaccone - vedere immagini 1 e 2), dove il terreno gentilmente digradante si muta improvvisamente in una palude di fango ed erbe madide, tra le quali l'acqua emerge da diversi punti nel campo.

Sono rintracciabili molti brani letterari antichi che narrano di questo prodigioso ruscello (il più famoso è certamente quello reperibile nel trecentesco "Dittamondo" di Fazio degli Uberti). Uno di questi brani è tratto dal volume "Mazzetto di fiori istoriali" pubblicato nel 1682 da Scipione Marioni, un aristocratico ed erudito eugubino, che riporta le parole scritte da Monsignor Lodovico della Valle, Prefetto di Norcia e della Montagna (immagine 3), il quale ebbe la possibilità di visitare la sorgente il giorno martedì 1 maggio 1640:

«Doppo il pranzo, accompagnato dalli Consoli nuoui, e vecchi della Città, fui alla Campagna à vedere TORBIDONE, ch'era ritornato trè giorni sono; Fiumicello, che molti anni stà sotto Terra, e molti altri ritorna, e scorre, e poi nouamente sparisce, nascendo in un Campo di San Benedetto, à piedi di Vallacone, lontano à Norcia un miglio in circa».

Esattamente come più di trecento anni fa, il Torbidone ora corre di nuovo attraverso la campagna (immagine 4): un segno apparentemente innocuo e gioioso della potenza immensa e terribile dei terremoti.

8 Jul 2017

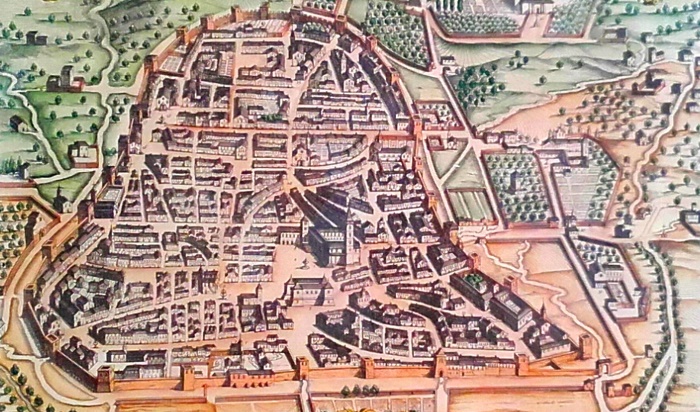

The Apennnine Sibyl - A Mystery and a Legend publishes a rare print showing Norcia after the 1703 ruinous earthquake

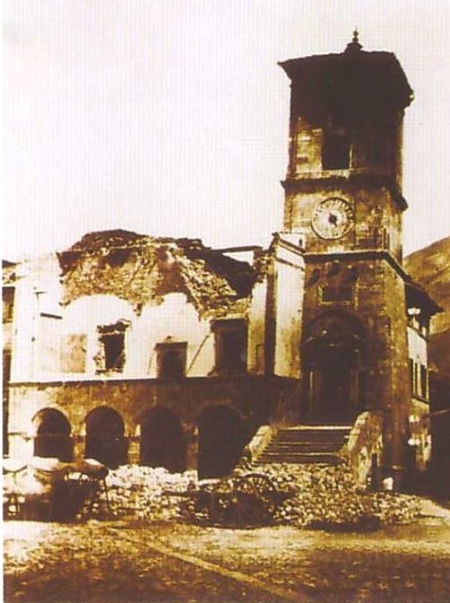

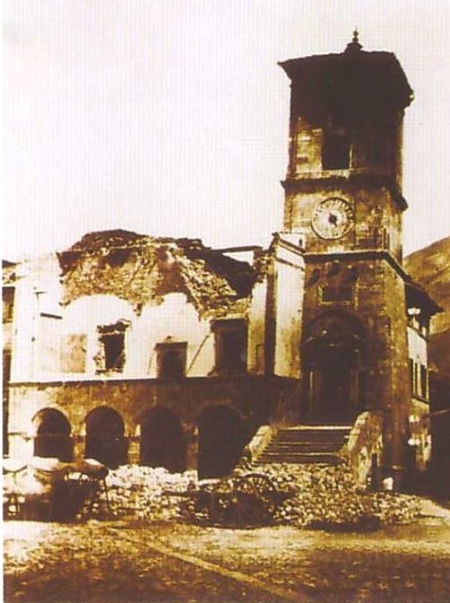

The scene is one of ghastly destruction: Piazza San Benedetto is portrayed as it appeared to visitors just two years after the appalling earthquake that hit the town of Norcia on January, 14 1703.

The Basilica is in ruins, the façade almost broken, the belfry just about to collapse, its bells laying miserably on the ground. The Town Hall has no roof anymore, the arched walls gaping on the square covered with debris. Only the Castellina stands still - as ever, a stronghold whose bulk is able to withstand any earthquakes.

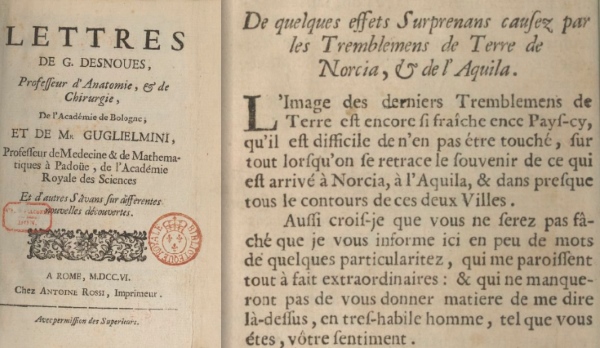

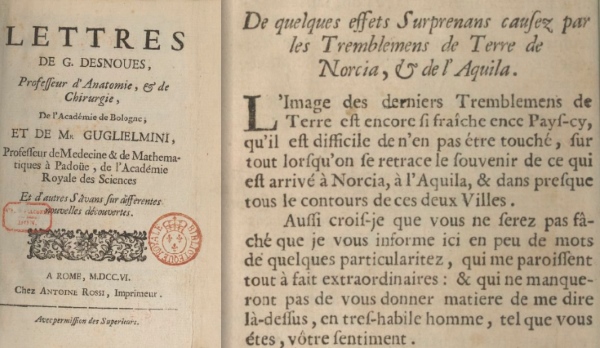

This is the awe-striking drawing possibly sketched by Domenico Guglielmini, an Italian scientist who visited Norcia in 1705, and subsequently published in Guillaume Desnoues' “Letters” in 1706. He was in the town with Francesco Antonio Bufalini, the architect who had been sent by Pope Clemens XI to carry out the reconstruction works.

«The effects of the last earthquakes are still so fresh in this land that is hard not to be moved by the vision», writes Mr. Guglielmini. An earthquake «that submerged, so to speak, the town of Norcia where 800 people died, and almost all neighbouring hamlets were turned upside down with the loss of nearly all inhabitants».

It is worth noting that the buildings shown in Guglielmini's drawing are exactly the same displayed by Dutch cartographer Ioannes Blaeu in his famous seventeenth-century map of Norcia: the same belfry and the same Town Hall, as they were before the 1703 earthquake.

A vision from the past, truly moving, which reminds to us how this land can be, at the same time, beautiful and merciless.

You can download a higher-resolution version of Guglielmini's drawing from here.

Sibilla Appenninica - Il Mistero e la Leggenda pubblica una rarissima stampa di Norcia dopo il rovinoso terremoto del 1703

La scena è di terrificante distruzione: Piazza San Benedetto è ritratta come appariva al viaggiatore solamente due anni dopo lo spaventoso terremoto che colpì la città di Norcia il 14 gennaio 1703.

La Basilica è in rovina, la facciata quasi del tutto frantumata, il campanile in procinto di crollare, le campane adagiate miserevolmente al suolo. Il Palazzo Comunale non ha più tetto, le arcate vuote occhieggianti sulla piazza ricoperta di detriti. Solo la Castellina regge ancora - come sempre, una fortezza la cui massa è in grado di resistere ad ogni scossa.

È questo l'agghiacciante disegno tracciato probabilmente da Domenico Guglielmini, uno scienziato ed erudito che visitò Norcia nel 1705, disegno che fu in seguito pubblicato nelle "Lettres" a Guillaume Desnoues nel 1706. Guglielmini si trovava in città assieme a Francesco Antonio Bufalini, l'architetto che era stato inviato da Papa Clemente XI per la ricostruzione.

«Gli effetti degli ultimi terremoti sono ancora così freschi in questa terra che è difficile non esserne toccati», scrive Guglielmini. Un terremoto «che ha sommerso, per così dire, la città di Norcia, dove perirono 800 persone, e quasi tutti i villaggi del circondario furono scossi e rivoltati con la perdita della maggior parte dei loro abitanti».

È interessante notare come le costruzioni visibili nella stampa di Guglielmini siano esattamente le stesse mostrate dal cartografo fiammingo Ioannes Blaeu nella sua famosa mappa di Norcia, risalente al diciassettesimo secolo: lo stesso campanile e lo stesso Palazzo Comunale, così come essi erano prima del terremoto del 1703.

Una visione dal passato, vera e toccante, che ci ricorda come questa terra possa essere, al contempo, bellissima e crudele.

È possibile visualizzare una versione a più elevata risoluzione della stampa di Guglielmini qui.

11 Mar 2017

The Marcite (the Marshes) of Norcia

«Here the crystal substance of water and the green fabric of grass - unlike elements, endowed with dissonant and contrasting qualities - merge gently one into another, in a perpetual and consonant murmur, by which the visitor is entranced, delighted, appeased.

Glittering veils of liquid moisture run over the emerald herbage, gleaming in the sunlight with countless, shimmering specks of light, as if they were precious stones, a bounty forgotten by some distracted dame of the meadows: indeed, a goddess as regal as munificent; tiny rivulets of purest water make their way among the swaying weeds, soaking into the verdant turf that shines with a radiant, dazzling glare, as the soil, wet through, turns into a soft, yielding material, which is like the magical blanket that shelters the slumbers of nymphs; small cascades and miniature eddies combine playfully among the grass, creating little basins of water, which summon to a freshening, solitary ablution; in such places, at dusk, the sylvan gods may possibly be seen, as they discreetly take their ritual bath.»

Le Marcite di Norcia

«È qui che il cristallo dell’acqua e il verde dell’erba, princìpi dissimili, sostanze discordanti dall’ineguale carattere, si congiungono penetrando dolcemente l’uno nell’altro, mormorando un’armonia perenne che il visitatore incanta, rasserena e acquieta.

Veli di liquida frescura corrono sulle erbe smeraldine, che brillanti effondono nel sole miriadi di sfavillanti riflessi, come gemme preziose dimenticate in gran numero da chissà quale incauta signora dei prati, divinità magnifica e prodigale; rivoli d’acque purissime si aprono la strada tra gli steli ondeggianti, immergendosi nel verde manto dal minuzioso, splendente riverbero, mentre il terreno, intriso in profondità, si fa cedevole e soffice, come la coltre che il sonno protegge delle ninfe; cascatelle e minuscoli gorghi si intrecciano carezzevoli tra le erbe, creando piccole pozze che invitano ad un refrigerio oscuro, appartato; presso le quali, a certe ore della sera, è forse possibile spiare gli dei del bosco, segretamente immersi nel bagno lustrale.»

11 Feb 2017

A Scottish photographer in Norcia after 1859 earthquake

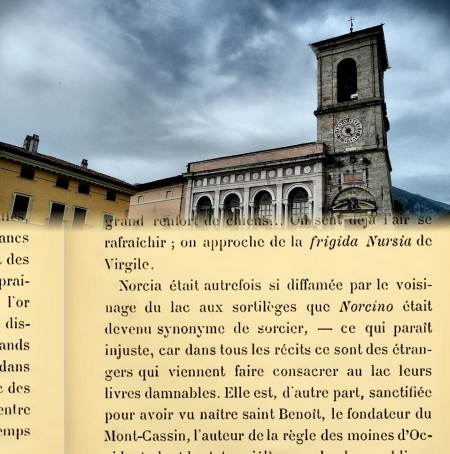

In 1859 Norcia was struck by a ruinous earthquake. Scottish photographer Robert Turnbull Macpherson, a famous artist in Europe and in Rome, took a few shots of damaged Norcia which are the sole recorded evidence of that long-gone destruction.

His portrait of St. Benedict's Square with the collapsed Town Hall is a masterpiece of three-dimensional rendering of buildings on a 2D photographic surface.

For a strange coincidence - one of those that sometimes occur with no logic explanation at all, except whimsical ones - Mr. Macpherson was married to the niece of British writer Anna Brownell Jameson, whose quote from “Diary of an Ennuyée” I used as the opening sentence to my novel “The Eleventh Sibyl”:

«Had I never visited Italy I think I should never have understood the word picturesque. The very air of Italy is embued with the spirit of ancient mythology»

At that time I knew nothing about Mr. Macpherson, nor about his relationship with Norcia and Ms. Brownell Jameson: but artistic paths are so subterranean and unknown that magic is often working behind the veil of our material, tangible world.

Un fotografo scozzese a Norcia dopo il terremoto del 1859

Nel 1859 Norcia fu colpita da un disastroso terremoto. Il fotografo scozzese Robert Turnbull Macpherson, artista famoso in Europa e a Roma, catturò alcune immagini della Norcia distrutta, le quali costituiscono la sola testimonianza di quei danni ormai dimenticati.

Il suo scatto di Piazza San Benedetto con il Palazzo comunale crollato è un capolavoro della resa tridimensionale degli edifici su di una superficie fotografica a due dimensioni.

Per una strana coincidenza - una di quelle che talvolta si verificano in assenza di qualsiasi spiegazione logica, e per le quali solo nel fantastico si possono trovare ragioni – Mr. Macpherson era il marito della nipote della scrittrice inglese Anna Brownell Jameson, una citazione della quale, tratta dal “Diary of an Ennuyée”, ho utilizzato come frase d'apertura del mio romanzo “L'Undicesima Sibilla”:

«Se non avessi mai visitato l'Italia, io credo che non sarei mai stata in grado di comprendere il significato della parola 'pittoresco'. Lo spirito delle antiche divinità aleggia ancora nel sole e nel vento d'Italia».

A quell'epoca nulla sapevo di Mr. Macpherson, né della sua relazione con Norcia e con Ms. Brownell Jameson: ma i sentieri dell'arte sono così sotterranei e misteriosi che la magia è spesso all'opera dietro il velo che si stende innanzi al nostro tangibile mondo materiale.

17 Dic 2016

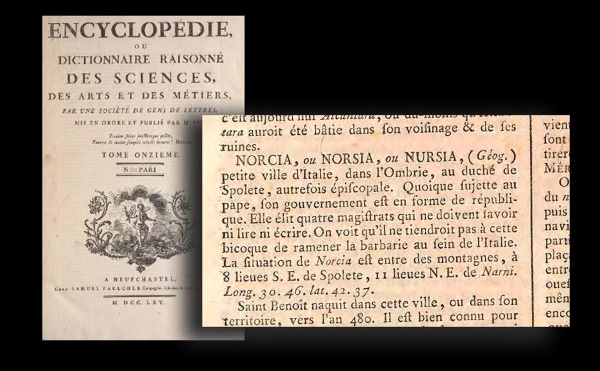

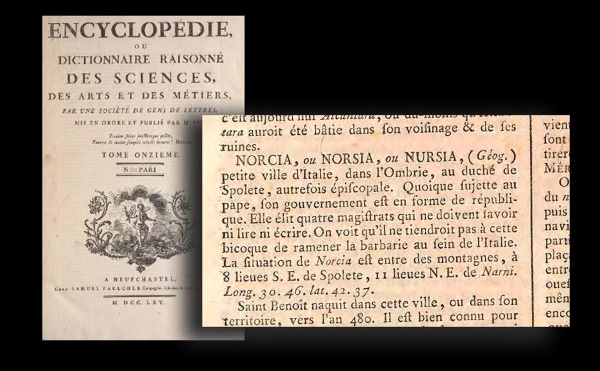

Norcia in the eighteenth-century French "Encyclopedie"

In past centuries, St Benedict's birthplace had achieved a peculiar renown not only because of its most illustrious holy man and its proximity to magical places such as the Sibyl's cave and the Lakes of Pilatus. The small town was also known for an odd rumor that had been collected and relayed by illustrious poets like John Milton.

It was commonly believed that Norcia was a sort of free republic in the very core of Italy's Papal States: a proud people whose self-rule was established under the motto «all learned people, get out of here!»

The hearsay was fully received by two famous French men of letters, Denis Diderot e Jean le Rond d’Alembert. In their universally-known masterwork “Encyclopedie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers” - a cornerstone of eighteenth-century culture – they wrote the following words:

«NORCIA, or NORSIA, or NURSIA (Geog.) small Italian town, in the Umbria region, within the Duchy of Spoletium, once a bishop's see. Though subject to Pope's rule, its government is republican. Four magistrates are elected, who are required to be fully ignorant of reading and writing. Everyone can see that it should not be this hamlet's work to bring the barbarian customs back into the very heart of Italy. Norcia is placed in a mountainous region...»

An odd renown indeed; and yet it was universally known in Europe owing to Milton's fame and the widespread diffusion of the “Encyclopedie” throughout Europe.

Norcia nella settecentesca "Encyclopedie" di Diderot e D'Alembert

Nei secoli passati, la città di nascita di San Benedetto aveva acquistato una particolare notorietà non solo a motivo dell'illustre fondatore dei monachesimo occidentale, e a causa della sua vicinanza a luoghi magici quali la grotta della Sibilla e i Laghi di Pilato. La piccola città era anche conosciuta per una strana diceria che era stata raccolta e rilanciata dal famoso scrittore inglese John Milton.

Si credeva infatti comunemente che Norcia fosse una sorta di libera repubblica posta nel cuore dello Stato Pontificio: gente fiera, il cui autogoverno fosse stabilito all'insegna del motto “escano fuori li sapii!” (“via tutti i letterati!”).

Questa voce era stata pienamente accolta anche da due famosissimi uomini di lettere, Denis Diderot e Jean le Rond d'Alembert. Nella loro diffusissima opera “L'Enciclopedia, o Dizionario ragionato delle scienze, delle arti e dei mestieri” - una pietra miliare della cultura settecentesca – essi riportarono infatti le seguenti parole:

«NORCIA, o NORSIA, o NURSIA (Geog.) piccola città italiana, in Umbria, nel ducato di Spoleto, una volta sede vescovile. Benché soggetta al papa, il suo governo è in forma di repubblica. Essa elegge quattro magistraati che non devono sapere né leggere né scrivere. Si vede come non sarebbe spettato a questo piccolo villaggio di riportare la barbarie nel seno dell'Italia. Norcia è situata tra le montagne...»

Davvero una strana nomea; e, addirittura, molto ben nota in tutta Europa, grazie alla fama di Milton e alla capillare diffusione dell'Enciclopedia.

13 Dic 2016

Norcia, il poeta John Milton and the rule of the illiterate

Did you know that Norcia was once famous for a queer renown that the town had achieved across Europe? Strange as it may seem today, a peculiar rumor had spread in past centuries that, in Norcia, scholars and learned men were not welcome, and local countrymen rather preferred to be ruled by illiterate leaders!

John Milton, the prominent seventeenth-century English poet, the author of the celebrated poem Paradise Lost, reported this piece of information as an entry into his "A Commonplace Book". Milton noted down (as a quote in Italian) that «in Norcia, a town lying in the Papal States, when a public session is held, an outcry is raised, that all learned people be cast out; and no public office is ever assigned to scholars, nor to any men of letters; on account of that, the town was ever so sensibly ruled that, when Italy was struck by grim hardship in the past, neither the inhabitants of Norcia nor the people living in the small hamlets in the countryside suffered any inconvenience from the ravaging adversity».

From then on, for people throughout Europe Norcia became a sort of proud flagship against literacy and rule exercised by affluent social classes.

People in Norcia knew nothing about that at the time. Even today they are utterly unaware of this peculiar renown they have enjoyed in their long-gone past.

Norcia, il poeta John Milton e il governo degli illetterati

Sapevate che Norcia era un tempo famosa a causa di una peculiare diceria che si era sparsa in Europa a proposito della piccola città italiana? Per quanto possa oggi apparire strano, una strana voce circolava nei secoli passati, e cioè che, a Norcia, gli studiosi e i letterati non fossero i benvenuti, e che la gente del luogo preferisse essere governata da persone ignoranti!

John Milton, l'illustre poeta inglese del diciassettesimo secolo, autore del celebrato poema “Paradiso Perduto”, riportò questa diceria in una voce del suo “A Commonplace Book”. Milton annotò (come citazione in lingua italiana) che “«in Norcia terra dello stato Ecclesiastico quando s’entra in consiglio si grida fuori i letterati; e i uffici non si danno ne a Dottori, ne a letterati; e con tutto ciò quella terra nelle passate calamitose penurie che afflissero Italia si governò tanto prudentemente che ne gli abitatori di essa ne alcune delle ville di quel distretto sentirono gli incommodi di così generale estremità».

Da allora in poi, per tutti in Europa Norcia divenne una sorta di orgogliosa bandiera contro la cultura e il potere esercitato dalle ricche classi superiori.

La gente di Norcia nulla sapeva di tutto ciò. E anche oggi essi sono totalmente ignari di questa particolare notorietà della quale la città ha goduto nel lontano passato.

17 Nov 2016

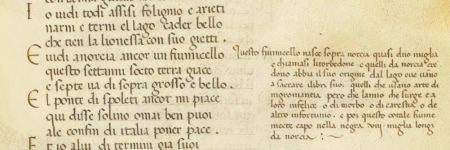

The awakening of the legendary Torbidone river in Norcia

A curious aftermath of Oct, 30th earthquake is the awakening of the river Torbidone (see image), a streamlet that had run unseen through its own unknown subterranean course for decades. Now it has re-surfaced, and this is no news at all.

Despite its being an insignificant rivulet in a remote Italian countryside, Torbidone was largely known and mapped in the sixteenth-century Vaticans's Gallery of Maps (see image). In the fourteenth century, it had been celebrated by Tuscan poet Fazio degli Uberti, who in his poem "Dittamondo" wrote the following words (see images):

«E vidi a Norcia ancor un fiumicello: questo sette anni sotto terra giace, e sette va di sopra grosso e bello» (Dittamondo, Book 3, Chapter 10)

Fazio's line can be translated as follows: «And I beheld in Norcia a small stream: for seven years it lies underground in disguise; then, for seven years more, it runs over the grasslands with its rushing, invigorating waters».

Thus, the Torbidone had achieved great renown for its appearance and subsequent disappearence following the earthquakes that used to struck the Sibillini region across the decades: a behaviour connected to the nature of the Sibillini Range's rock, carved in limestone and pierced by unseen caverns and cavities.

But there was more to that: in past centuries, Norcia was an eerie, mysterious place where people came to meet a Sibyl - who had her dwelling in a cave on Mount Sibyl's cliff - or consecrate a grimoire - at the sinister Lake of Pilatus. And the Torbidone was part of this legendary lore, as Andrea Morena from Lodi writes by his own hand next to Fazio's word in a fifteenth-century manuscript (see image):

«Questo fiumicello nasce sopra Norcia, quasi due miglia, e chiamasi Torbedone, e quelli da Norcia credono abbia il suo origine dal lago ove vanno a sacrare i libri suoi quelli che usano arte di nigromantia; però che [danno?] che surge e a loro infelice o di morbo o di carestia o de altro infortunio. E poi questo cotale fiume mette capo nella Negra (Nera) nove miglia longi da Norcia» (This rivulet starts some two miles from Norcia, and it is called Torbedone, and the people in Norcia believe it flows from the lake who is visited by those who perform the art of necromancy to consecrate their spellbooks, so that for this reason the region is troubled by scourge and famine or other affliction. Then this streamlet ends up into the Nera some nine miles across from Norcia).

It is evident the close link among the eerie legend about the Apennine Sibyl, the dark lore connected to the Lake of Pilatues, tha savage nature of the Sibillini Range and the blood-curdling and devastating earthquakes which strike the region across the centuries: all of that rendered Norcia one of the most mysterious places to be found in Italy and Europe. A fascination which is still alive today.

Il risveglio del leggendario fiume Torbidone a Norcia

Un curioso effetto collaterale del terremoto del 30 ottobre 2016 è rappresentato dal risveglio del fiume Torbidone (vedere immagine), un ruscello che ha seguìto per decenni propri percorsi segreti attraverso il sottosuolo. Ora, il fiume è risalito alla superficie, e non si tratta certo di una novità.

Malgrado si tratti di un insignificante fiumiciattolo posto in una remota zona dell'Italia centrale, il Torbidone era ben conosciuto e addirittura mappato nella Galleria delle Carte Geografiche situata in Vaticano e risalente al XVI secolo (vedere immagine). Già nel XIV secolo, il fiume era stato celebrato dal poeta toscano Fazio degli Uberti, il quale aveva scritto questi versi nel suo poema “Il Dittamondo” (vedere immagini):

«E vidi a Norcia ancor un fiumicello: questo sette anni sotto terra giace, e sette va di sopra grosso e bello» (Dittamondo, Book 3, Chapter 10)

E dunque, il Torbidone aveva acquistato una grande fama a causa del suo apparire e poi sparire sottoterra a seguito dei terremoti che periodicamente colpivano la regione dei Monti Sibillini nel corso dei secoli: un comportamento legato alla natura carsica della roccia dei Sibillini, costituita da calcare traforato da invisibili caverne e cavità.

Ma c'era anche qualcosa di più: nei secoli passati, Norcia era considerata come un luogo sinistro e misterioso, presso il quale strani visitatori si recavano per incontrare una Sibilla – che pareva risiedere in una caverna posta sul picco del Monte Sibilla – o per consacrare libri di magia presso i paurosi Laghi di Pilato. E anche il Torbidone era parte integrante di questo patrimonio di leggende, come scrive Andrea da Lodi, di propria mano, accanto alle parole di Fazio in questo manoscritto del "Dittamondo" risalente al quindicesimo secolo (vedere immagine):

«Questo fiumicello nasce sopra Norcia, quasi due miglia, e chiamasi Torbedone, e quelli da Norcia credono abbia il suo origine dal lago ove vanno a sacrare i libri suoi quelli che usano arte di nigromantia; però che [danno?] che surge e a loro infelice o di morbo o di carestia o de altro infortunio. E poi questo cotale fiume mette capo nella Negra (Nera) nove miglia longi da Norcia»

È evidente lo strettissimo legame che sussisteva tra la Sibilla Appenninica, i miti tenebrosi che circondavano i Laghi di Pilato, la selvaggia natura del massiccio dei Monti Sibillini e i terrificanti terremoti che periodicamente colpivano quel territorio: tutto ciò faceva di Norcia uno dei luoghi più misteriosi che esistessero in Italia e in Europa. Un fascino che sussiste intatto ancora oggi.

14 Nov 2016

Earthquakes from the abysses of time

Julius Obsequens, a Latin author who lived in the fourth century AD, wrote in his "Prodigiorum Liber" ("The Book of Supernatural Events") that in year 99 B.C. "the hallowed temples of Norcia were razed to the ground by an earthquake":

«Nursiae aedes sacra terrae motu disiecta»

So earthquakes have always been stricking Norcia and the Sibillini Mountains throughout the fathomless abysses of time.

This is confirmed by an astonishing finding that INGV scientists, jointly with researchers from a university in Rome, retrieved while performing an excavation campaign on the versant of Mount Vettore in 2005: as they dug through a known fault line, they found a strange lump of dark-colored earth, laying a few meters beneath ground level. After analysing it, it turned out that it was an ancient clod of grass: it had fallen into the breaking fault being split apart under a terrific earthquake. According to the carbon-14 dating, all that had happened in year 200 B.C.

This is the reason for the mysterious renown achieved by the Sibillini Mountains: the power of the Gods was hidden beneath the lofty peaks, and from time to time it awakened and struck mortals with deadly blows.

Terremoti dagli abissi del tempo

Giulio Ossequente, un autore latino vissuto nel IV sec. d.C., scrisse nel suo "Prodigiorum Liber" che nell'anno 99 a.C. "i sacri templi di Norcia furono rasi al suolo dal terremoto".

«Nursiae aedes sacra terrae motu disiecta».

I terremoti, dunque, hanno colpìto Norcia e i Monti Sibillini più e più volte, nel corso di innumerevoli secoli.

Ciò è ulteriormente confermato dall'incredibile scoperta che gli scienziati dell'INGV, insieme ai ricercatori di un'università romana, effettuarono durante una campagna di scavo condotta nel 2005 sui fianchi del Monte Vettore: scavando lungo una linea di faglia, fu trovata una strana massa di terra scura, che giaceva alcuni metri al di sotto del livello del suolo. Dopo averla analizzata, si comprese che si trattava di un'antica zolla d'erba: essa era caduta nella frattura che era stata aperta nella superficie erbosa da un terribile terremoto. Sulla base della datazione con il metodo del carbonio 14, tutto ciò era avvenuto intorno al 200 a.C.

È questa la ragione della fama misteriosa che ha sempre circondato i Monti Sibillini: il potere degli Dèi era racchiuso al di sotto di quei picchi vertiginosi, e - di tanto in tanto - si risvegliava colpendo i mortali con colpi distruttivi.

7 Nov 2016

Destructive earthquakes in the eighteenth century

Norcia and the earthquakes: in the eighteenth century, the seismic waves struck the town with mighty power in a frosty February of the year 1703, the earth writhing and wailing in anguish under an earthquake whose estimated magnitude was 6.8 Richter. Again, the ground was shaken furiously on May, 12th 1730, only twenty seven years later, «terremotum infausta die XII maii», and the walls, houses, towers, everything was crushed and shattered down under the giant thrust that dismembered the earth; and, in the ruthless roar, from the tall, stately belfry of the Town Hall, «shaken by the earthquake», «three huge bronze bells» were hurled down onto the square. And the bell tower stood there, «leaning crumpled sideways, at risk of imminent collapse». Destruction after destruction, death after death; according to the old chronicles, many years later Norcia would still bear the appearence of «a city never restored from its ruined state, as it still displays at every corner the mournful, hideous scars of the earthquakes».

I terremoti distruttivi del diciottesimo secolo

Norcia e i terremoti: nel diciottesimo secolo, le onde sismiche avevano colpito la città con immane potenza. In un gelido febbraio del 1703, gli ingranaggi nascosti nel sottosuolo si erano nuovamente inceppati, incagliati sotto l’effetto funesto di forze sovrumane, spezzandosi, cosicché la terra si era dimenata in un lamento di angoscia. Ancora, il suolo si era nuovamente contorcerto il 12 maggio 1730, dopo soli ventisette anni, «terremotum infausta die XII maii», e le mura, le case, le torri, tutto era caduto e si era infranto sotto la spinta titanica che smembrava la terra, e nel fragore atroce il magnifico ed elevato campanile del Palazzo Comunale, «sconcertato dalle scosse», aveva scaraventato sulla piazza «tre grosse campane, restando tutto curvo e piegato da una parte, in prossimo stato di cadere». Distruzione su distruzione, morte su morte; dopo molti anni, Norcia appariva ancora come «una Città che non è mai risorta dalle sue ruine, e presenta in ogni angolo i lugubri, e spaventevoli effetti di terremoto».

6 Nov 2016

The 1859 earthquake